You, a rookie: With no theater right now, it must be tough to be a theater critic.

Me, an expert: My good woman, you are forgetting WrestleMania. [Swishes opera cape.]

“Evil is the natural climate of wrestling.” —Roland Barthes

In hour six, my resistance finally crumbled. Surely a phrase exists for the way WrestleMania 36 bested me in mano-a-mania combat — I’m reaching for it, but my fingers keep slipping off its oiled surface. Because at 10 p.m. Sunday, even metaphor broke.

It had been a full weekend of watching streamed WrestleContent — three hours on Saturday, with only short commercial breaks for the WrestleSponsor Snickers™, then a longer bout on Sunday. I’d grown complacent over my wine. This wasn’t so hard to follow, I thought, as the announcers cued another video package explaining a long-standing inter-brand quarrel or mused on whether or not best friends would back each other up in a five-way rumble for dominance. In high school, I was a big fan of the soap opera Santa Barbara, but I could only watch daytime dramas in the summer, so starting mid-June, I had to quickly acclimate to months-old changes in feuds and affairs. Here I used those old muscles, getting wise to rivalries in seconds, probably because I was letting the announcers do my thinking for me. “She’s one of the most underrated superstars in history,” I said, wisely, to the room, having heard of Bayley — the longest-reigning combined SmackDown Women’s Champion — only minutes before.

But as we headed into the second half of hour five, there was still a tinge of irony to my watching. I was busily taking notes (I have 8,000 words of transcribed WrestleMania if anybody … wants … it …) and jotting down with a sneer all the times I saw through the illusion that everything was okay. I was not exactly doing Sherlock-level deduction: Denied by the coronavirus and a governor’s stay-at-home order, the Orlando-based WWE had reluctantly moved “wrestling’s biggest night” out of the 65,000-seat Raymond James Stadium in Tampa and into their Performance Center, a training facility whose interior — dolled up with a million moving lights — still looks like a cross between the boxing corner at Crunch and the lobby of an Equinox. With no fireworks, no one singing “America the Beautiful,” and no audience, the WWE tried to put on a spectacle without spectators, filming match after match on the closed set and splicing them together with video packages until it had enough for two full evenings.

Other than the no-doubt Herculean efforts of the set and lighting designers, key adjustments had not been made. Standing in a ring in an echoing black void, surrounded by only a few scrambling cameramen and two announcers, wrestlers were yelling into microphones as if they were fighting to be heard over the roar of thousands. During one backstory video, we watched a wrestler scream to an empty room, calling it “this sold-out crowd at the Performance Center.” Maintaining their customary choreography of victory, winners held up belts to be admired by nobody, and one poor woman even lifted her arms, encouraging a nonexistent audience to applaud. There’s already a suspension of disbelief that undergirds professional wrestling, a collaboration between audiences and the performers that creates the kayfabe doublethink. And yet this further suspension — asking us to believe that there is a crowd in a room that we can see is empty — felt like the bad kind of delusion.

I’ve wondered about the future of theater in an era of social distancing. Will we someday deliberately stage plays to empty houses and broadcast the films? Well, the WWE had the resources and disregard for corona protocol to jam through a test case, shooting the matches and interstitials just as the shutdown came into operation. And I can tell you that an empty room does things to performance that you don’t want to know about it. It drinks energy; it siphons it away.

Eliminating the audience does, though, leave each element isolated and even elegant — particularly the peacocky costumes, which often boast something embroidered right on the tushie. There’s often real wit involved: Seth Rollins, who calls himself the Monday Night Messiah, appeared in a sleek white outfit with a half-shoulder cape — kind of a bishop-on-top, business-on-the-bottom look. Occasionally a heavyweight wrestler would arrive in the traditional “nuthin’ fancy” and an oiled chest as a sorbet between rich dishes, so the 50-something Goldberg — hulking in briefs and ready for business — offered a refreshing contrast to the gold-skull epaulets, the rainbow-bright tracksuits, or the pouty King Corbin, who entered wearing a crown and a Game of Thrones–type cloak (i.e., an Ikea sheepskin over his shoulders).

Like contestants at the Miss Universe pageant, international wrestlers often dress in homage to their home country, so the strapping Drew McIntyre, an honest-to-god Scot, enters in the classic Scottish gear: the sleeveless leather duster made famous by Highlander. When he drops it, there’s a sassy little wink to what we know about traditional clan fighters — he wears tiny leather underwear, to remind us that in the auld days, he wouldna bothered. (McIntyre swiftly and rather anticlimactically won his title bout with the pyramidal Brock Lesnar, thanks to his signature Claymore kick, a horizontal leap of both legs extended, toes pointed for the opponent’s throat.)

Each performer must work surrounded by the black, bleak, windowless Performance Center, so their clothing takes on totemic significance — each is a sculpture in a black gallery. The darker-clad wrestlers are sometimes difficult to make out against this shadowy backdrop. Take Aleister Black, for instance. As the announcers tried to play word games with his name (surely the lowest-hanging of the pun fruit), the bearded Black entered, a shredded leather cloak hanging to his feet. When he passed beneath a strobing magenta light, he looked like a floating white head. Sadly, the elaborate black horns rising from each shoulder were nearly invisible in the gloom, particularly since they’re the key signal that he’s referring to some sort of Viking-flavored-metal legacy. (It doesn’t help when the announcers tell us he’s from Amsterdam, since the Vikings weren’t Dutch. But what, he was going to come dressed as a canal?)

In any normal wrestling environ, the black-costumed characters would cut a somber figure — the sobriety of villainy against the hurdy-gurdy heroes and crowd itself. Here, though, with black clothing blending into the walls, they become accidentally vulnerable. Nothing distracts our gaze from their pale faces, their untrimmed beards, the sweat and fear both rolling into their eyes. The bellowing, spray-tanned good guys can dazzle us into forgetting that these are employees being pressed to work in a pandemic, but the devils can’t hide. They look human in close-up, and they look lost. At least Black is an anti-hero on the rise: He efficiently won his contest with Bobby Lashley, who brought his wife-manager Lana to the match to shout from the sidelines. Lana gave some advice which led (literally) to Bobby’s downfall, and Lashley appeared extravagantly bewildered about his defeat. But at least they left together. Black just packed up all his Satanist-panic clichés and disappeared.

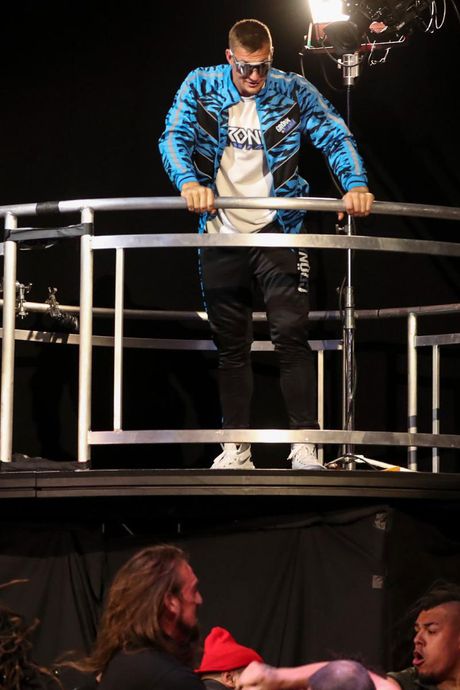

When the evenings had shape and thrust, it was thanks to the announcers, who were responsible for delivering streams of exposition, getting the subtext out there, on the carpet, where they could pummel it. The nominal “host” was Rob Gronkowski, onetime Patriot tight end and full-time doofus, who, it turned out, was also trying to win the 24/7 wrestling prize, which must be “defended at all times.” The Gronk wore a tiger-stripe jacket in Gatorade-blue and mirrored sunglasses, stood on a high platform, and generally behaved like a DJ at an under-attended school dance. “I know how to start a party on Saturday night and finish it 30 hours later!” he crowed to no one, trying to pump up a party that would not get started right. I far preferred the first evening’s announcing duo, John “Bradshaw” Layfield and Michael Cole. They were skilled at that sportscaster imitation discourse — “Careers will be defined,” “No, legacies will be created” — which turns redundancy into dialogue. Their text also allowed them to take bizarre stances, just so we could understand immediately where we were in a given story. Without the boos and cheers of the crowd (a.k.a. thousands of crowd-collaborators workshopping “rootability” in public), they simply had to tell us who was naughty and who was nice. Layfield, referring to Bayley and her pal Sasha’s rather underhanded work in the ring: “That’s a role model! You tell kids, ‘You gotta cheat, you gotta do whatever you gotta do to win.’” So efficient! Even a swiftly moving play like Glengarry Glen Ross would have taken more than an hour to get somewhere similar.

For the most part, performers came in, stated their essential feature (cockiness or disregard for his opponent’s family for the villains, grit for the heroes), fought, and departed. The longest episode was a no-disqualification battle between the wild-eyed Edge and his friend–slash–bête noire Randy Orton, which ranged all through the Center, fighting on tabletops and in hallways and finally on top of a trailer in what seemed to be the building’s garage. The combat was creative, using anything at hand, and the announcing was also creative, describing things like padded walls and melamine tabletops as “steel.” But there wasn’t quite enough text to fill the time, so Orton just told Edge that he was thumping him because he loved him, over and over and over. When Edge finally dispatched him with a chair de grâce, everyone watching (me, an ice-cream sandwich) was relieved.

Innovation didn’t necessarily pay off — the basics worked best. Midway through the first evening, Jimmy Uso, John Morrison, and Kofi Kingston, wrestlers whose regular tag-team partners were indisposed, engaged in a three-way struggle. The titles — a belt with shiny disks — was hung above the ring, and the wrestlers were encouraged to bring light aluminum ladders into the ring to (a) bop one another with, and (b) climb up to grab the belt. The choreography was often stunning, featuring wild, high-spinning flips off the top rope and into the space around the ring, but the trio’s timing seemed a bit dozy. This led to many adorable moments of wrestlers needing to elaborately slow down their clambering, as they waited for the next tackle, or to find that their hands couldn’t quite grab the belt so obviously within reach. Kingston’s hand would open and shut, nerveless as the claw in an arcade game, until, that is, the trio had flipped and flopped like bright sparkling fish for the correct amount of time and were allowed to find their ending.

So what broke me? You’d think it was the first-night finale, in which the Undertaker, well into his 50s and with a fighting strategy I would refer to as “please run into my fist,” met A.J. Styles for a Boneyard Match. This produced video package got us out of the Performance Center and into a cemetery (Vince McMahon’s backyard?), where they could both try to throw the other into a freshly dug open grave. Spooky choruses sang on tape, floodlights popped on at key moments, flash pots flashed, and the Undertaker literally buried his opponent. All this was charming. I thought of the New York downtown flurry of “fight-sicles” circa 2007, like Point Break Live! or anything staged by the Vampire Cowboys. If you decide to watch it, I recommend pairing this sequence with a Chablis.

But I had no reference point for the second evening’s big produced sequence, the Firefly Fun House match. Its absurdity defeated my ironic detachment; it was deranged, back-asswards, Alfred Jarry–esque, a barbaric yawp that tore down my mind’s careful walls. Wine? Spilled. Ice-cream sandwich? Forgotten. The video references whizzed by. My illusion that I could keep abreast of decades of mythology crumbled. The official dramaturgical term is, I’m afraid, “bananapants.”

John Cena, who has become a very nice actor, appeared “as himself” to fight Bray Wyatt, with whom he has had much beef. Currently, Wyatt plays both a Dr. Jekyll–like host of a cuddly children’s television show (PeeWee’s Playhouse manqué) and a Mr. Hyde persona called the Fiend. He and his creepy puppets, including a Vince McMahon doll, ushered Cena into a trippy fun house of the mind, a flashback-filled limbo where Cena was taunted with various heel turns, either real or imagined. Would he go the way of Hulk Hogan in the New World Order era? Or be forced to return to his own, cringey Doctor of Thuganomics character, a rapping persona he dropped to appear more kid-friendly? He made the best he could of his torture: Dr. Cena — his hat backward, his rhymes tight — slammed his opponent with insults that I could only stand up and salute. For instance, he had a recommendation for Wyatt’s future puppeteering: “YOU CAN PUT MY JUNK IN A GLOVE & CALL IT ‘MR. SUCK IT,’ BRO.”

The value of the Firefly Fun House bout, for me, was that its bonkers-ness overwhelmed my critical faculties. At other points in the six and a half hours (the same length as Angels in America!), I had time to think about how reckless and even cruel the WWE was being, asking performers to come sweat and shout and spit at each other in late March, when they should have known better. The various commentators appearing periodically to call it a gift to the fans or a way to raise spirits had not convinced me, and I had come to be fearful first for the older wrestlers (bless every grizzle on Goldberg’s cuboid head), and eventually for everyone. Indoctrinated by my hours with WrestleMania, the other violence no longer fazes me. I fully expect a well-upholstered man to bounce face-first off a turnbuckle without ill effect, or a young woman to get choked into near-unconsciousness and rise again, full of beans. But can the WWE guarantee that their actual workers will come out of this experience unscathed? The key marker of villainy in many of the story lines is a disregard for another fighter’s family. So. I leave that here.