My primary associations with Swedish people come from my mother, who is of Swedish blood and looks it. (Picture a blonde garden gnome, but beautiful.) I think of Swedes as pragmatists with a streak of whimsy, nature-loving, uncommonly skilled at digesting dairy products. The author Patrik Svensson, a Swedish man, embodies all of these traits except possibly the dairy one, which I canÔÇÖt verify from his Book of Eels but suspect to be true.

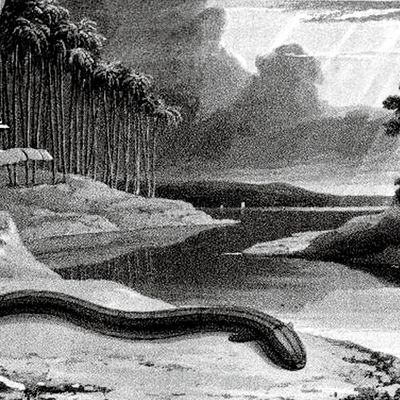

How do you feel about eels? For reasons that arenÔÇÖt the eelÔÇÖs fault ÔÇö its shape, color, lateral movements, nocturnal nature ÔÇö you may feel the way I do, which is: Yuck. Svensson is the most recent thinker to contend with what scientists call, IÔÇÖm not kidding, the ÔÇ£Eel Question.ÔÇØ I was drawn to his book the way a child is drawn to an unusual foul smell (ÔÇ£Hey, Mom, smell this. Mom!ÔÇØ), and it was as much a boon to my mental life as a blow to my social one. For weeks after reading I found myself cornering people at parties to obliterate them with a machine-gun spray of eel facts.

But according to The Book of Eels, IÔÇÖm not alone in my eelmania. Aristotle thought eels were born from mud, spontaneously generating in the form of a slithering worm. Pliny the Elder guessed that eels reproduced by rubbing up against rocks, loosening particles from their bodies that turned into new baby eels. Archaeologists in Egypt have discovered tiny sarcophagi containing mummified eels. When Sigmund Freud was a teenager, he cut up 400 eels in hopes of figuring out how they procreated ÔÇö failing to decode the creatureÔÇÖs sexuality but succeeding in a contribution to what we might call HistoryÔÇÖs Most On-the-Nose Anecdotes.

The Eel Question is actually a number of questions surrounding, mostly, the European eel, Anguilla Anguilla ÔÇö an eel so nice they had to name it twice. The first question is: How do they mate? We donÔÇÖt know, because no human has ever witnessed two of these eels getting it on. (Which means, yes, nobody has succeeded in breeding these eels in captivity. They simply wonÔÇÖt be farmed.) The second question is: Why do they live such bizarre lives? It is the bizarre life of Anguilla anguilla that Svensson outlines.

First, eels are fish, not aquatic snakes. (You probably knew this. I, an idiot, did not. Sea snakes, however, are actual snakes.) They have scales and gills, though both are barely perceptible. They are slimy. All specimens of Anguilla anguilla are born in the Sargasso Sea, which is vaguely near Bermuda and is the only sea with no land boundaries. After they are born, the baby eels swim thousands of miles and wind up in freshwater lakes, ponds, and streams, where they hunt at night and exist unobtrusively. They can move over land to get from one body of water to another (creepy). They have a phenomenal sense of smell. (One scientist claimed you could put a single drop of rosewater in Lake Constance, at the foot of the Alps, and an eel would smell it.) At a seemingly random point in their lives, they return to the Sargasso Sea to mate and die. How do they find their way back? How do they get there so quickly ÔÇö a few thousand miles, in some cases, in just a few months? Still unanswered, these questions. The point is, if youÔÇÖve caught an eel in a lake or seen an eel in a pond, that eel came from an enigmatic ocean far away, and we donÔÇÖt yet know how or why. Also, after roughly 40 million years on Earth, eels are mysteriously dying off at a rapid rate. Probably it is our fault.

SvenssonÔÇÖs interest in eels was a birthright. As a child, he would visit a local stream with his father at twilight to set up eel-catching devices as bats flitted above them. At dawn, theyÔÇÖd return to collect the dayÔÇÖs catch, which SvenssonÔÇÖs mother would fry in butter with a pinch of salt and pepper. (Svensson hated the taste: ÔÇ£greasy, slightly gamy.ÔÇØ) By the authorÔÇÖs account, every form of eel fishing has a spooky aspect to it. He describes a variety called klumma, which involves threading a sewing needle and sticking it through worm after worm, until you have a kind of gruesome worm necklace, which you lower into a known eel territory. When the eel bites, a skilled klumma practitioner will tug the worm necklace and fling the attached live eel into his boat. Svensson describes his fatherÔÇÖs thrilling, horrifying method of collecting worms for klumma: The older man affixed some exposed electrical wires to a pitchfork, shoved the pitchfork into the familyÔÇÖs damp backyard, sent 220 volts through it, and watched as the lawn turned into ÔÇ£one big living organismÔÇØ of wriggling bait.

In Basque territory, young eels come in ÔÇ£on the tide on cold nights, under a full or crescent moon and preferably when the sky is slightly overcast.ÔÇØ They float in shoals over the surface like ÔÇ£enormous, silvery tangles of seaweed.ÔÇØ Fishermen illuminate the water to reveal this living blanket of fragile fish, which they collect in nets by hand. The term for an eel in this stage is glass eel, and it is the only window of an eelÔÇÖs life when it might, if you unfocus your vision and push yourself, be considered cute. A handful of glass eels looks like angelÔÇÖs-hair pasta, if it were made of molten silver. The Basque are one of the few groups of people who still catch and eat them, serving the baby animals piping hot in a ceramic dish with a special wooden fork so diners can avoid burning their lips. In Britain, eels are cooked into omeletlike ÔÇ£elver cakes.ÔÇØ

In 2016, a delightful and somewhat paralyzing book called The Soul of an Octopus was published. It was responsible for causing many people ÔÇö including, to my surprise, myself ÔÇö to stop eating octopus. In my case, it wasnÔÇÖt the creatureÔÇÖs cosmic intelligence that rendered it inedible but its playfulness. How could I eat a creature that seemed to possess a personality trait that I ranked among my favorite in humans? Or that possessed a personality, in the true sense of that word, at all? Midway through The Book of Eels, I paused and wondered, Had I ever eaten eel? I couldnÔÇÖt remember. Likely not. Still, if youÔÇÖre an eel-eater, you could easily read this book and maintain an appetite for the fish ÔÇö though they are becoming scarce, so you shouldnÔÇÖt overdo it. But the eel is not particularly intelligent. When in captivity, it does not interact with humans in complex and heartrending ways. And compared to the octopus, it is much harder, though not impossible, to make the case for an eelÔÇÖs soul.

The Book of Eels is not the first general-audience book about eels to be published. ItÔÇÖs not even the first general-audience book about eels called The Book of Eels: A previous one came out in 2002 by the writer Tom Fort. I will say itÔÇÖs a little odd to duplicate a title as recent as this, especially when so many other options exist. (Here are some free suggestions from me: WhatÔÇÖs the Deel With Eels? or Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Eels But Were Too Ashamed to Ask or Taming Your Inner Eel.) There are parts of the book where Svensson seems maybe a little too enamored of his subject. When he says that ÔÇ£the eelÔÇÖs secretive side is also the secretive side of humans,ÔÇØ you might pause and ask: Is it, though? Still, it is a charming and itch-scratching contribution to the eel canon ÔÇö less an analysis of eels than a meditation on their glories. If you donÔÇÖt think of yourself as someone who might enjoy meditating on eel glory, well, I didnÔÇÖt either, and here I am transcribing my encounter for publication.

*This article appears in the May 11, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!