My grandfather, who died several years ago at the age of 98, was a Turkish archeologist who specialized in ancient Hellenic ruins. He spent almost half a lifetime digging up a long-forgotten Greek town on the Aegean coast of Turkey, a site that happened to be right next to a coal-mining facility. It both tickled and saddened him to see the old world juxtaposed with the new, timeless Greek columns and graves framed against huge piles of black, black coal. He wasn’t much of a romantic, but he did love the poetry and majesty of myth. When I was a child he’d glance out over the horizon, at the ships and sailboats passing in the blue distance, and tell me about how through these very Aegean waters had sailed the navies of Paris and Menelaus. He loved to enliven the everyday with evocations of the ancient world.

(He was obsessed with Troy, and spent years writing a book about it.) I, a snot-nosed kid for much of this time, paid only scant attention to his stories.

Only later did I realize what a gift he was giving me.

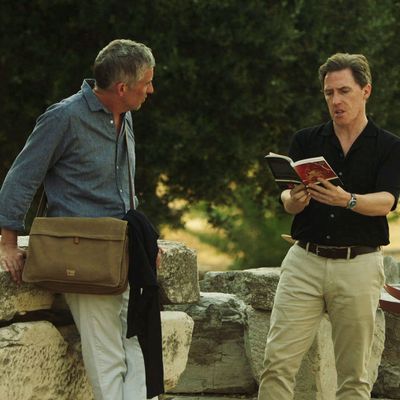

So, weirdly, I was reminded of my grandfather as I watched The Trip to Greece, the fourth and final installment of the film and TV series following Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon as they make their way around the hotels and tourist spots and fine-dining establishments of the world. This film (which actually begins in Turkey, in the area around Troy) opens and ends with words from The Odyssey, and at various points evokes the stories of Odysseus and Aeneas as Coogan and Brydon eat, joke, imitate, and niggle their way through Greece. The parallels are inexact and rough, and to director Michael Winterbottom’s credit, the film doesn’t try too hard to adhere to any kind of mythic structure. But what does remain at the end of this final and most despairing of the Trip entries is a sense that the past is never quite done with us, that today’s heartbreaks and passions and tragedies are merely variations on ancient patterns.

We sense throughout The Trip to Greece that reality is catching up to our heroes, in ways both cosmic and personal. But to be fair, there has always been a dark edge to these films. The food and the jokes were often cut with more somber passages, with Winterbottom making deft use of Michael Nyman’s elegiac, brooding music (some of it lifted from more ostensibly serious films, a couple of them also Winterbottom’s). When the duo first arrive on the island of Lesbos, they run into a co-star of Coogan’s from another project (Kareem Alkabbani, who also appeared in the Winterbottom-directed Greed) who compels them to visit a refugee camp. The implication — only suggested, but clearly there, especially given some of the director’s previous work — is that these refugees, the people fleeing their war-torn and devastated homelands, are themselves the modern-day versions of those desperate travelers of ancient history.

Even here, however, the jousting doesn’t let up. “It would be good for Rob to see a refugee camp,” Coogan says, self-importantly; on the way back, Brydon forces Coogan into admitting that he doesn’t even remember the name of the Arab co-star who just showed them around. The Trip films have a remarkable (and welcome) tonal consistency, and there’s plenty here of those lively, escapist elements that have made these movies so charming and irresistible (and such a comfort at this particularly bizarre moment in time). Coogan and Brydon are, of course, playing fictional, heightened variations on themselves; their onscreen personae, filled with petty jealousies, are constantly looking to one-up one another like an old couple. Coogan loves to mention all the BAFTAs he’s won, and the dramatic, serious roles he’s done; at one point, he proudly reads a review of his recent film Stan & Ollie, which praises his performance while slagging him as a person. Brydon, famous for his impersonations, often uses them to find ways to get under Coogan’s skin. (Coogan, being the more famous of the two, usually finds himself the butt of the movie’s jokes.)

My favorite bit is one of the sweeter ones: After Coogan relates an utterly inane non-story about how he recently sat under a tree on his property and had to leave because there were too many flies, Brydon transforms into a talk-show host wildly praising Coogan’s narrative skills (“the new Ustinov!”); even Coogan cracks up at that one. The imitations they roll out are familiar ones — Anthony Hopkins, Sean Connery, Robert De Niro, Ray Winstone — and while those are fun, what makes the whole thing work so well is the fact that these grown men with their dueling impressions continue to be so wildly competitive with each other. (For the record, Brydon does a way better Dustin Hoffman, while Coogan’s Mick Jagger kills. I don’t much care for either of their Brandos.)

The Trip to Greece goes in an interesting direction in its final scenes, as one protagonist has to deal with a personal tragedy while the other experiences a sweet, amorous reunion. It’s all in keeping with the film’s evocations of myth, suggesting that when the world hits us with all its force — in ways both good and bad — we seek to hold on to the eternal and unchanging, to things that speak to the fact that we are not alone. It’s a kind of wisdom that sometimes comes with age, which is why it can be easy to miss, or ignore.

That reflective and timeless quality might be the most surprising element of The Trip to Greece, which for all its finality leaves things in open-ended fashion. And so, a series built around two funnymen making Michael Caine jokes while eating poached fish closes on Homeric invocations and the melancholy murmur of undiscovered countries. The trip is ending, but it’s not over yet.