ItÔÇÖs late afternoon in Cambridge, England, and Olivia Laing has just come in from her garden. SheÔÇÖd been planting in the long, narrow plot she dotes on like a member of the family, with its properly algaed pond and rows of seedling trays lined up in a small glasshouse. TheyÔÇÖve had a spell of sunshine, she explains, rather funny for April ÔÇö then she laughs at the coincidence of what sheÔÇÖs just said. Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency, her collection of essays about how ÔÇ£art shapes our ethical landscapes,ÔÇØ is out this week in the U.S. She refers to it as a series of ÔÇ£weather reports from the road,ÔÇØ dispatches from about 2016 to 2018 about how ÔÇ£the political weather, already erratic, was only going to get weirder.ÔÇØ Well, yes. You could say that.

Laing, 43, has acted as a kind of cultural sage for the past four years, an accidental literary grande dame of the emotional havoc wrought by late capitalism and digital disconnect. SheÔÇÖd written two widely praised works of nonfiction before 2016: To the River charted the meandering path of the ancient Ouse (the small but strong river in which Virginia Woolf, a frequent touchstone for Laing, packed her pockets with rocks and drowned in the first years of World War II), and The Trip to Echo Spring, which assembled the stories of six male alcoholic writers from the early-to-mid-20th century (Cheever, Hemingway, the usual suspects) and considered the reciprocal relationship between irascible boozehounds and their artistry.

But 2016ÔÇÖs The Lonely City, published in the heat of the last presidential cycle, turned her into a cult figure for those urban dwellers who, surrounded by the then-packed streets of New York, felt unhappily exempt from it all. A blend of memoir, biography, and cultural criticism, Laing intersperses the story of her own lonely year in the East Village with analyses of the work of artists like Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, and David Wojnarowicz, men who turned their longing for connection into art that ÔÇ£shows what loneliness looks like ÔǪ and takes up arms against it.ÔÇØ SheÔÇÖs become a bit of an expert on the emotional states of locked-down city dwellers. Book clubs have taken up The Lonely City again. Chlo├½ Sevigny raved to the Cut about its import in her life. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm doing huge amounts of interviews,ÔÇØ she confessed, ÔÇ£about what loneliness means and how we can survive loneliness.ÔÇØ

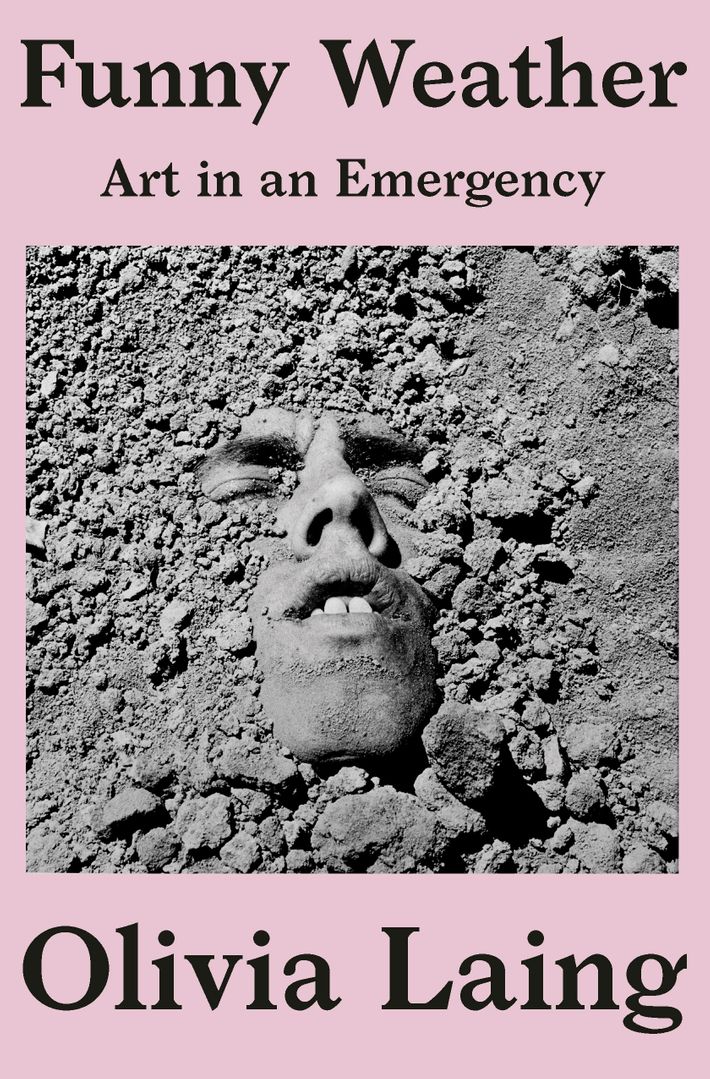

The guiding principle in all LaingÔÇÖs work is productivity through pain ÔÇö try to imagine a more troubled and addled group than Woolf, Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Warhol, Wojnarowicz, Henry Darger. ThatÔÇÖs enough pooled misery and genius to sustain melancholic biopic makers for decades. But unlike the class of biographers who seem to find immense pleasure in dishing out steaming piles of their subjectÔÇÖs suffering, Laing is radically empathetic, a writer-activist. She sees Funny Weather as ÔÇ£a companion in tough times.ÔÇØ The essays take the form of short treatises on the lives of particularly beleaguered artists, book reviews, and ÔÇ£love lettersÔÇØ to phenoms like David Bowie and critic John Berger. The collection is strongest, however, at its center, with a group of essays Laing composed in real time, reacting to incidents like the Grenfell Tower fire in London, the shooting at the Pulse nightclub, and the ban on Muslim travelers, essays that connect the keening of tragedy and suffering to the ways that art resists and repairs. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm going as a scout,ÔÇØ she writes in the bookÔÇÖs introduction, ÔÇ£hunting for resources and ideas that might be liberating or sustaining now, and in the future.ÔÇØ

Laing ruefully laughs when I ask about her ability to see whatÔÇÖs coming down the pike. ÔÇ£If you write about painful subjects,ÔÇØ she says, ÔÇ£catastrophe and the future of the internet and the future of the planet, at some point what you say is going to start seeming very meaningful.ÔÇØ

An early memory for Laing: crowds of adults packed in around her 11-year-old self on the London streets; feathers and laughter; fury, too. ÔÇ£I was at gay pride in ÔÇÖ88, when Section 28ÔÇØ ÔÇö the cruel Thatcherite law banning the promotion of gay materials and discussion of homosexuality in British schools ÔÇö ÔÇ£had come in. People were seriously sick, young beautiful men were suddenly looking like old, emaciated figures in the street.ÔÇØ The sick people were HIV-positive, and the tumult, she explains, turned the parade ÔÇ£really, really angry.ÔÇØ Witnessing that, she continues, ÔÇ£put something inside me for the rest of my life.ÔÇØ Art as action and action as art.

LaingÔÇÖs parents divorced when she was 4. She left Buckinghamshire with her mother, who came out as a lesbian after the split. They headed for Portsmouth, where her mother became involved with a woman who was ÔÇ£an alcoholic ÔǪ a coercive, controlling, very frightening person.ÔÇØ Eventually, she left the relationship. In the years that followed, Laing recalls morphing into ÔÇ£a wild teenager.ÔÇØ She turned down a place at Cambridge and instead embarked on a series of road protests, living quite literally in trees. ÔÇ£We moved around by walkways,ÔÇØ Laing writes in Funny WeatherÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Feral,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£two lines of blue polypropylene that ran from tree to tree, thirty feet above the groundÔÇØ ÔÇö┬áto create a human barrier against encroaching motorway developers. LaingÔÇÖs existence became a protest against standard modes of living and, as she moved into adulthood, almost a form of performance art. The year she turned 20, keen to stay out in the open, she moved into a homemade bender, ÔÇ£the traditional summer dwelling of Romany Gypsies,ÔÇØ made from ÔÇ£bent poles of coppiced hazel covered with canvas.ÔÇØ She lived in it, alone on a dilapidated Sussex farm, for four months.

ÔÇ£I was frightened all the timeÔÇØ Laing writes. ÔÇ£I felt more exposed than I ever have since, almost unravelled by it, paranoid that I was being watched by the inhabitants of the scattered houses whose lights I could see winking through the fields at night.ÔÇØ The roots of The Lonely City came from this sensation. One of the central experiences of loneliness, she explains in the book, is ÔÇ£the way a feeling of separation, of being walled off or penned in, combines with a sense of near-unbearable exposure.ÔÇØ What will everyone think when they see how lonely I am? ÔÇ£My twenties,ÔÇØ she says now, ÔÇ£were a completely-drop-out, another-world kind of decade.ÔÇØ She spent them mostly among the flora, training for five years as a herbalist devoted to patients with anxiety ÔÇö a hands-on practice run for the kind of writing sheÔÇÖd eventually pursue.

Laing made her way back to what she calls, trillingly, ÔÇ£the more con-VEN-tional worldÔÇØ at 29, when she got the itch to write. She did an internship for the Observer and then, ÔÇ£the miracle of my life,ÔÇØ was hired as their deputy books editor. She lost her job just a couple years later in the midst of the 2008 recession. On her last day at work, another editor told her, ÔÇ£There is a very small window in a womanÔÇÖs life in which you can write ÔÇö you have to get through the window.ÔÇØ So she pitched To the River in 2009 and has steadily published since. Now sheÔÇÖs wrapping up the very last pages of her next book, Everybody, her sixth in less than a decade.

ItÔÇÖs easy to find comparisons between our current state, locked up in studio apartments and interacting feebly with the same recurring faces, and that of The Lonely CityÔÇÖs artists. Though he created an atmosphere of creative chaos in his home/studio the Factory, Warhol was frequently tongue-tied in public. Wojnarowicz, isolated by his HIV diagnosis, used his body to drive home the inherent isolation of homophobia and othering. But Laing is quick to point out one key difference she finds inspiring. In the book she writes, ÔÇ£loneliness feels like such a shameful experience, so counter to the lives we are supposed to lead, that it becomes increasingly inadmissible.ÔÇØ On her book tour for The Lonely City, 20-somethings (ÔÇ£almost always very young peopleÔÇØ) often whispered confessions of loneliness to her, unburdening themselves of a secret that was hollowing them out. But these days, strangers are readily admitting their loneliness to the internet, using social media less like a darkened confessional booth and more like an AA meeting. (ÔÇ£Hello, IÔÇÖm Hillary, and IÔÇÖm lonely as hell right now.ÔÇØ) Laing sees this as revolutionary, and potentially key to the art that might emerge from 2020.

She used to be worried about the digital divide and how it refracted our identities. Now she calls those concerns ÔÇ£really old-fashioned.ÔÇØ Laing (who quit Twitter) thinks social media is finally, in the midst of globally shared suffering, offering up empathetic art. ÔÇ£People, at the moment theyÔÇÖre realizing their own physical vulnerability, are also having an extreme realization of interconnection,ÔÇØ she says. She remains suspicious of the rapid-fire deployment of news cycles in one day. Whizzing through the latest coronavirus headlines can dull us down to reactionary outrage bots, she explains. ÔÇ£That feeling is what really made me want to write Crudo,ÔÇØ she continues, ÔÇ£with a sense of what would happen if I just logged, in real time, completely raw data of what it feels like to be consuming this information.ÔÇØ

Laing wrote her 2018 bullet ricochet of a novel in seven weeks, and set it over the course of those same seven weeks. Her publishing house trusted her enough to leave it entirely unedited, understanding that her Beat-style, ÔÇ£first word, best wordÔÇØ mentality was key to the projectÔÇÖs integrity. Crudo is two stories layered into one. Its narrator is the now-deceased Kathy Acker, a real-life experimental novelist known for lifting other writersÔÇÖ sentences and making them her own. But its plot follows LaingÔÇÖs real life in the late summer of 2017, as she marries and follows the news of the world through ÔÇ£her scrying glass, Twitter.ÔÇØ At her wedding reception someone shouts ÔÇ£Steve BannonÔÇÖs resigned.ÔÇØ Hurricane Maria whips in and Trump tweets about ÔÇ£HISTORIC rainfall.ÔÇØ Justice crusaders retweet their way to self-satisfaction. Through it all, Kathy alternates between hovering over her screens and trying to repress the headlines. ÔÇ£She missed the sense of time as something serious and diminishing,ÔÇØ Kathy thinks, ÔÇ£she didnÔÇÖt like living in the permanent present of the id.ÔÇØ Reading it leaves bruises. ItÔÇÖs not pleasant, but when you reach the last page it does feel like the laxative has done its job.

Funny Weather, by contrast, is like a flashlight feeling its way through the dark, flicking between the headlines and hoping for a way to connect. It moves through the smoke-saturated lungs of the Grenfell Tower fire victims, the incarcerated figure of an immigrant detainee tossed around BritainÔÇÖs bureaucracy, the sewn-together lips of protesting refugees who had washed up on so-called First World shores and received paltry welcomes. Laing canÔÇÖt help but bring herself back to our human casing. A childhood wrapped in the AIDS crisis has shaped her interests, and watching the images of bagged bodies moved via forklift at New York hospitals stirs up memories of how ÔÇ£governments might prove negligent or uncaring about the deaths of some of their citizens.ÔÇØ But while the atrocities of governments and the ravages of nature pile up, she points to the resonance of resistance-style art. Those refugeesÔÇÖ mouths, for example, call to mind the stitched lips of AIDS protesters in Rosa von PraunheimÔÇÖs 1990 documentary Silence = Death. ÔÇ£The word ÔÇÿstitchÔÇÖ is a double-edged prayer,ÔÇØ Laing writes. ÔÇ£It means the last bit of anything ÔÇö the stigmatized, say, or the devalued. And it means to join together, mend or fasten, a hope sharp enough to drive a needle through flesh.ÔÇØ

Watching the pandemic news has left Laing too twitchy to read much fiction, she says. She can write, however, for stretches of eight hours at a time, and when we talked she was wrapping up the very last pages of Everybody, her treatise on the question, What is the root of the desire to limit peoples physical freedoms, to constrict people based on the kind of body theyre born into? It features essays on Nina Simone, Malcolm X, Susan Sontag, and more. Its about making a better world, she explains. I want to think about the people who have come up with solutions for better worlds, more beautiful worlds, more equitable worlds  Ive thought about how we got into this fucking terrible mess, and now I want to think about other solutions. Im betting it comes out just in time to help a virus-depleted populace find a way back into their skins.