Titus Kaphar loves art history, but he takes from the canon what he wants and turns it toward his own ends. The MacArthur-winner (and Ted Talk-er) is subverting these ÔÇ£classicalÔÇØ styles to use them to address the history of slavery and racism. Now represented by Gagosian, Kaphar describes his latest paintings, From a Tropical Space, as a ÔÇ£surrealist, fictional Afro-futuristic narrativeÔÇØ about black mothers and the disappearance of their children.

Black women have not been represented as Madonnas, Venuses, or odalisques, Kaphar observes. ÔÇ£What we have is the depiction of black folks in general, and black women specifically, as enslaved and [in] servitude.ÔÇØ This series, which Kaphar hopes to translate into a film one day, is a conversation about the Madonna paintings and MichelangeloÔÇÖs Piet├á. ÔÇ£These are mothers mourning the loss of their children,ÔÇØ he says.

Although the New York exhibition of this work has been postponed, Kaphar is the focus of GagosianÔÇÖs latest ÔÇ£Artist SpotlightÔÇØ through May 12.

LetÔÇÖs talk about From a Tropical Space.┬á

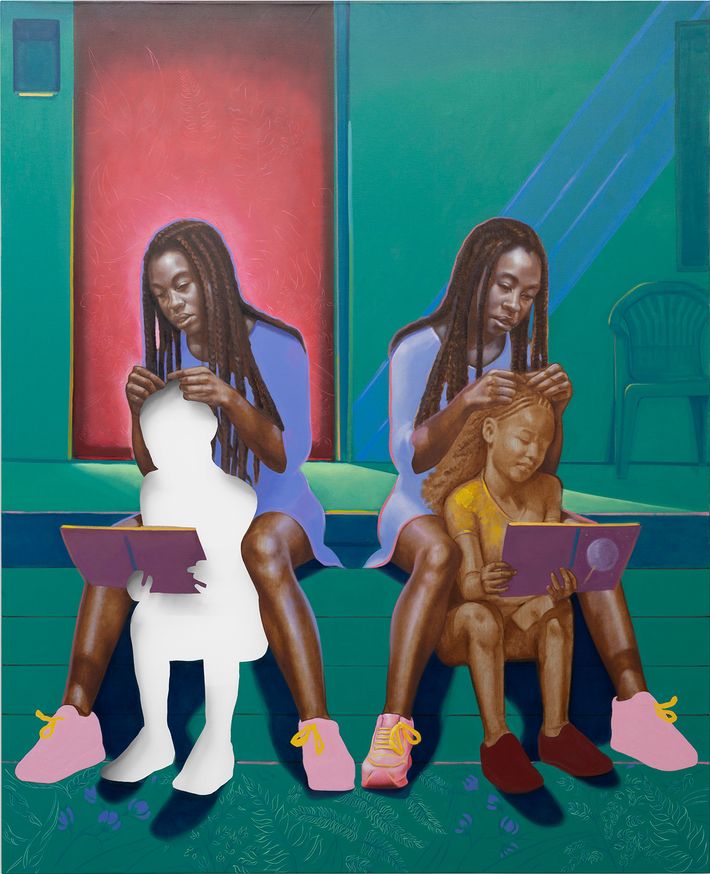

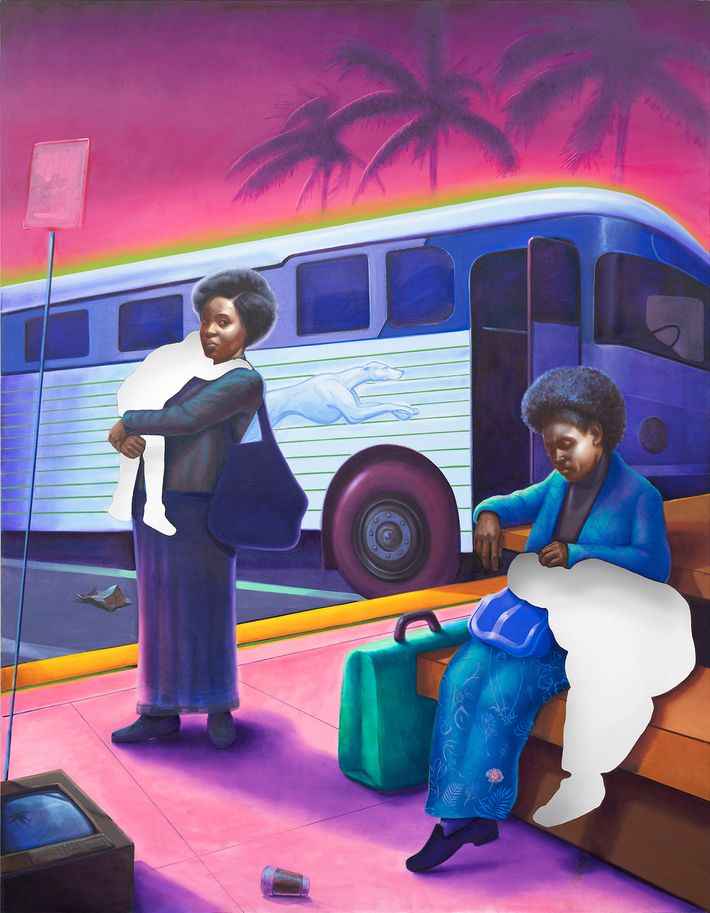

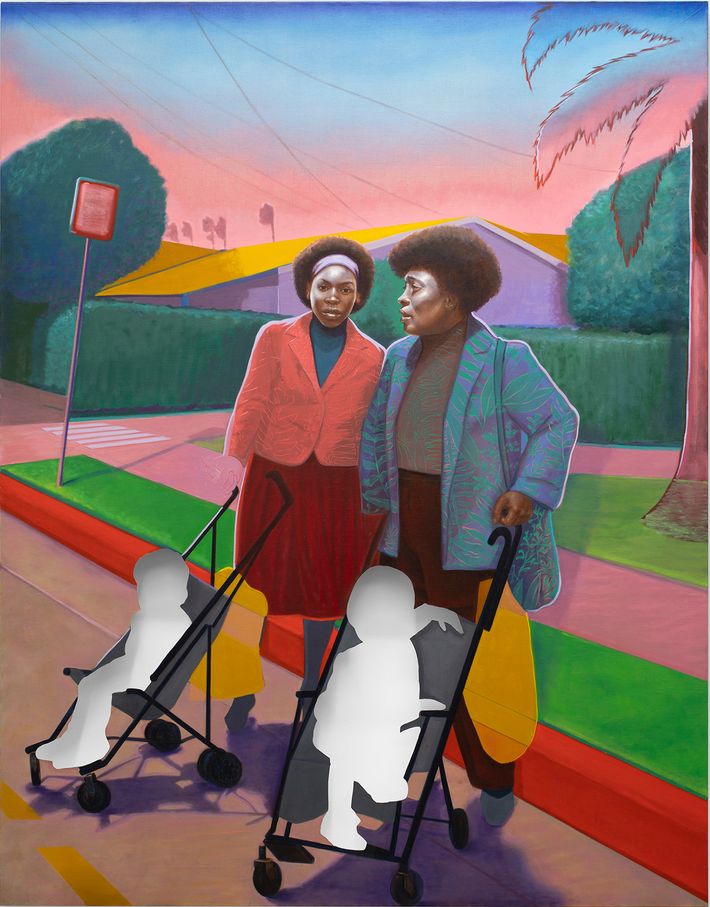

´╗┐When I started this project, it was unfamiliar to me. IÔÇÖd started this painting with these two women sitting on this couch with this otherworldly white light kind of dancing off their foreheads and where the children were on their laps were cut out and removed. I was really happy with the formal aspects of the painting, but it felt like it didnÔÇÖt fit with anything I was working on currently. So I stuck it to the side of the studio and then just periodically came back to it.

What made you come back to it?

´╗┐Part of the reason for me not being happy with it was, it felt like it was telling the story of black domestics, black women who were caretakers for white peopleÔÇÖs babies. And I just didnÔÇÖt want to go there. I felt like IÔÇÖve had that conversation before. Then a couple of months later, I came back to the painting and asked myself the question What in the composition insisted that the baby sitting on their laps didnÔÇÖt belong to them? And I had to admit that there was nothing.

It sounds like in deciding to pursue this series, you had to reassess your own biases.

´╗┐IÔÇÖm keenly aware of the way in which my own personal bias from studying Western art history will even influence the way that I even see the things that I make. Because of that, I almost decided just not to go on this particular journey. But when I realized that I needed to address this bias in myself, or rather my seeing, then it became something that was worth investigating. At a certain point, I was doing studio visits. I had folks walk into the studio, and as I suspected, their interpretations turned these mothers into domestic workers who were only momentarily caring for these children. The bias that I was experiencing in myself reiterated through other eyes, as well.

At first glance, the paintings look like a departure from your past work with its source material in art history.

´╗┐In the same way that the idea that these mothers are actually mammys, caretakers, domestics, au pairs, that understanding of the work is there because of a history, a reality that occurred. We donÔÇÖt see very many pictures of black women in art history, period. They are not our Madonnas. TheyÔÇÖre not our Venuses. They are not our odalisques. What we have is the depiction of black folks in general, and black women specifically, as enslaved and [in] servitude. When I looked at the compositions themselves, I realized that this [series] is a conversation about the Madonna. This is a conversation about the Piet├á. These are mothers mourning the loss of their children. So in that way, the relationship to art history is there. ItÔÇÖs just, the expression has changed.

The depictions of the children are actually excised from the canvas.

´╗┐TheyÔÇÖre cut out with the razor blade very surgically and removed. This whole body of work has unfolded for me as a sort of surrealist, fictional Afro-futuristic narrative. What became clear to me was that this was a story about black mothers and the disappearance of their children.

When I brought my mother into this studio, she saw one of the paintings and said, ÔÇ£You know, that reminds me of Flint.ÔÇØ My familyÔÇÖs from Michigan. I said, ÔÇ£What do you mean?ÔÇØ And she said, ÔÇ£Well, you know, obviously, the skyÔÇÖs not that color in Flint, but thereÔÇÖs a sense that the environment itself is toxic and will kill you.ÔÇØ And we live in communities like this all over the country. So the feeling, the mood, speaks to the trauma that these mothers are experiencing. That kind of anxiety, that kind of fear in these paintings, culminates into this moment of absence.

YouÔÇÖve said your work is not about COVID-19. But in a way, this work continues the conversation weÔÇÖre having about the effects of the pandemic, falling disproportionately on people of color.┬á

´╗┐So what weÔÇÖre talking about is the trauma. And how it works is, these moments of despair highlight the gap between communities in this country better than any expos├®, right? When weÔÇÖre talking about COVID, there are some specifics that have to do with the virus and health care, but the real lasting conversation that we should be having, the conversation that is going to go beyond COVID, is about that disparity in the communities. And so in that way, this body of work reflects what has been there. ItÔÇÖs not for the sole purpose of teaching somebody a lesson. ThatÔÇÖs not the way that I make my work. ItÔÇÖs for the purpose of me exploring my experience. The work is not about COVID, but there are a couple of pieces that the nature of whatÔÇÖs happening in the country right now canÔÇÖt be removed from the understanding of the piece anymore.

Tell me about your life right now.

´╗┐In a lot of ways, it hasnÔÇÖt changed anything. IÔÇÖm a very private person. IÔÇÖm not really on social media. IÔÇÖm a studio hermit, so I continue to be a studio┬áhermit. My family is fine. My brother got really sick in Detroit, where he lives. The hospitals there just didnÔÇÖt have enough space for people. So he had a temperature of 105. More or less, they just gave him Tylenol and sent them home. There was just no place to put people. And that speaks to that disparity that weÔÇÖre talking about in communities like this. In that way, IÔÇÖm affected like everyone else is affected, when their loved onesÔÇÖ health is at risk, but IÔÇÖm incredibly blessed, honestly. I mean lucky. I do a job where I can do it on my own and I can continue working. The quiet of the day has been helpful.

Congrats on joining Gagosian. HowÔÇÖd you end up deciding to join that gallery?

´╗┐I appreciate the congratulations about Gagosian. This is sort of misunderstood, the dates of these things are misunderstood, so let me clarify. I left Jack Shainman some time ago. IÔÇÖve been away from their gallery for almost two years, and I was managing my studio on my own. I was sort of representing myself in that way. I was actually fine with it. I hadnÔÇÖt been looking for another gallery but had been approached by several of the larger galleries. To be completely honest with you, when Sam Orlofsky asked me to do a studio visit, I really wasnÔÇÖt taking it that seriously. I never pictured myself as being at Gagosian, and I was, as I said, okay with being on my own. But when he came in, we went to NXTHVN first and we spent an hour and a half, almost two hours, over there. He really took time with each of the artists in the program. Then we came back and did a studio visit, and it was clear to me that he, as a representative of Gagosian, understood that the NXTHVN project is not a side thing for me. ItÔÇÖs not a hobby. This is fundamental to my practice.

NXTHVN is a part of your lifeÔÇÖs work now.

´╗┐ThatÔÇÖs right. Not only did they understand that, but they valued that. They stepped up and committed to supporting NXTHVN significantly as a part of their support for me. Our conversations werenÔÇÖt about money, which is what I think most people think when you move on to Gagosian or Hauser & Wirth or Pace or any of the big ones. Our conversation was about ideas and my values as an artist, and the essential aspect of my practice, which is NXTHVN.

WhatÔÇÖs next for you?

´╗┐ItÔÇÖs my dream to direct a film based on this body of work. IÔÇÖve been collaborating with a couple of friends of mine, and weÔÇÖre releasing the short piece relatively soon. IÔÇÖve collaborated with my friend Nigerian-American writer Tochi Onyebuchi. He and I have been collaborating on a piece of writing. And then, another friend of mine, Samora Pinderhughes, who was a great jazz pianist, weÔÇÖre collaborating on a music project. The gallery is actually releasing a kind of short episodic artistic film piece that will go along with this. WeÔÇÖll go along with this ÔÇ£SpotlightÔÇØ and exhibition. IÔÇÖm really excited about exploring these other mediums, music and film, to continue telling the story. The idea is that these works will be brought back and the second chapter of the narrative will be shown in Los Angeles next year. Hopefully by that point, we will have some of this cinematic piece to show at that time.

The colors in your pieces are so kaleidoscopic and luminous. Will the film be like that?

´╗┐ThatÔÇÖs exactly how I want the ultimate film to be. The saturation in these paintings is less about a geographic place and more about an internal landscape. It reflects the emotional pitch of whatÔÇÖs going on for these characters, even though in these moments they are frozen. They are still. WeÔÇÖve caught most of these women in the instance right before they realized the child has disappeared, but their anxiety is already rising.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

One work from the show, Braiding possibility (2020), will be available for sale beginning on Friday, May 8, at 6 a.m. ET, for 48 hours.