I have this pet theory about book recommendations. They feel good to solicit, good to mete out, but someone at some point has to get down to the business of reading. And there, between giving and receiving, lies a great gulf. No one can quite account for what happens. Reading, hopefully, but you never can be sure.

ItÔÇÖs that time again. Race is happening. Never mind that race is always happening but it is especially happening now, urgently happening, and god help you if youÔÇÖre not paying attention (though history will probably pardon your procrastination for history, too, is belated). I should clarify that ÔÇ£happeningÔÇØ here indicates agreement, a collective bargain that something has risen to the level of a thing by degrees of egregiousness or luck. It applies to anodyne hiccups as regular as a public figure putting their foot or face in it by using slurs and dark makeup, to the no less routine euphemized murders by police and their extrajudicial deputies. In any case there is the eruption of sentiment, none perhaps stronger than stupefaction on behalf of many at a loss with how to metabolize such a moment, how to metabolize race ÔÇ£happening,ÔÇØ despite the fact that race is always happening. The weeks and months following the 2016 presidential election was such a moment. The how could this happen meets the I told you so. They rendezvous at the anti-racist reading list.

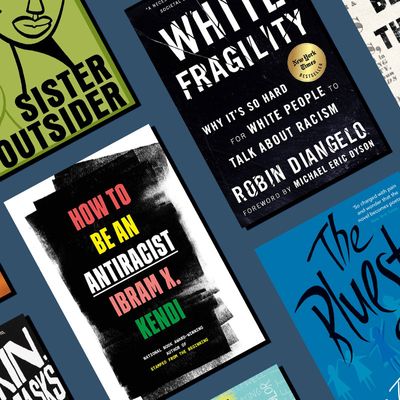

Despite the diversity of curators ÔÇö from legacy publications to small non-profits to historians to celebrities and other users with varying degrees of influence online (to your next door neighbor, probably) ÔÇö the anti-racist reading list varies little in its contents. The usual subjects are as long as the list themselves, we could chant them together: Sister Outsider, The Fire Next Time, Between the World and Me, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, The New Jim Crow, Their Eyes Were Watching God, Women, Race, & Class; maybe The Wretched of the Earth or Black Skin, White Masks if someone took a postcolonial theory course in college. With the exception of Ta-Nehisi Coates or Michelle Alexander or Claudia Rankine, contemporary titles on the list tend to baldly demonstrate the rise in general reader interest in how-to, come-to-Jesus talks about race. Race readers, I like to call them, books like Ijeoma OluoÔÇÖs So You Want to Talk About Race, Crystal Marie FlemingÔÇÖs How to Be Less Stupid About Race, and the mac daddies of the bunch, How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi and White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo. Amidst nationwide protests following the police killing of George Floyd, KendiÔÇÖs and DiAngeloÔÇÖs texts shot back up in the ranks of online retailers, along with other anti-racist list regulars.

An anti-racist reading list means well. How could it not with some of the finest authors, scholars, poets, and critics of the twentieth century among its bullet points? Still, I am left to wonder: Who is this for? The syllabus, as these lists are sometimes called, seldom instructs or guides. It is no pedagogue. It is unclear whether each book supplies a portion of the holistic racial puzzle or are intended as revelatory islands in and of themselves. Aside from the contemporary teaching texts, genre appears indiscriminately: essays slide against memoir and folklore, poetry squeezed on either side by sociological tomes. This, maybe ironically but maybe not, reinforces an already pernicious literary divide that books written by or about minorities are for educational purposes, racism and homophobia and stuff, wholly segregated from matters of form and grammar, lyric and scene. Perhaps better to say that in the world of the anti-racist reading list genre disappears, replaced by the vacuity of self-reference, the anti-racist book, a gooey mass.

An example ÔÇöThe Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, a usual suspect. The Bluest Eye is a novel whose grammar precedes exposition, and that grammar is crushing. Racism is relevant to the story to the extent that it is relevant everywhere, including the reluctant enclaves of migrated black characters whose discontinuous narratives fill the pages. In The Bluest Eye racism is the environmentÔÇöthe weather, the climateÔÇöand it makes the seasons turn, which is to say that it is happening all the time and therefore no more remarkable than March snowflakes in the Midwest. Every time I read the novel I am fascinated by how syntax expresses illness without pathology, how vernacular holds people together without fixing them. I am not sure if my attention would be drawn in the same way if I had approached MorrisonÔÇÖs fiction as a balm for my own latent racism and I am not sure what purpose the novel is meant to serve on an anti-racist list for someone desperate for understanding. I am sure such a person will find a lodestar worth grasping ÔÇö the novel stuns after all ÔÇö but whatÔÇÖs missed in the mission? A novel. And all that language.

I suppose the anti-racism reading list is exactly for that person, the person who asks for it. And yet the person who has to ask can hardly be trusted in a self-directed course of study, not if their yearning for gentle education also happens to coincide with their earliest exposure to books written by people who are not white. Anti-racism reading lists fail such a person, for they are already predisposed to read black art zoologically. Whether the stories are fact or fiction is irrelevant ÔÇö no one either knows or cares why certain writers express themselves in certain forms at certain times.

For such a list to do good, something keener than ÔÇ£anti-racismÔÇØ must be sought. The word and its nominal equivalent, ÔÇ£anti-racist,ÔÇØ suggests something of a vanity project, where the goal is no longer to learn more about race, power, and capital, but to spring closer to the enlightened order of the antiracist. And yet, were one to actually read many of these books, one might reach the conclusion that there is no anti-racist stasis within reach of a lifetime. Thus there cannot be an anti-racist canon that does not crystallize the very sense of things it proposes to undermine. The very assurance of absolution is tainted. The introductory race readers, for their faults, at least court the kind of audience who feels lost at sea in this whole race thing, and readers can lily pad from one to another until theyÔÇÖre ready for the tougher stuff. But it is unfair to beg other literature and other authors, many of them dead, to do this sort of work for someone. If you want to read a novel, read a damn novel, like itÔÇÖs a novel.

Calls to read more and to read this strike me as particularly funny, or at least comic, in the middle of pandemic when everyone admits that even our customarily wan attention spaces have been decimated. There are snappier places to glean the long-story-short of America, like podcasts, if it took someone this long to care. As a friend pointed out on Twitter, George Zimmerman was acquitted seven years ago. Donald Trump was elected four years ago. Black History Month happens every year. Cops kill all the time. The books are there, theyÔÇÖve always been there, yet the lists keep coming, bathing us in the pleasure of a recommendation. But thatÔÇÖs the thing about the reading. It has to be done.

*A version of this article appears in the June 8, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!