It’s been a month since AT&T-owned WarnerMedia launched HBO Max, and while the literal rollout went smoothly — the app works fine and there have been no big tech issues — the media narrative around the new streaming platform has been less than ideal.

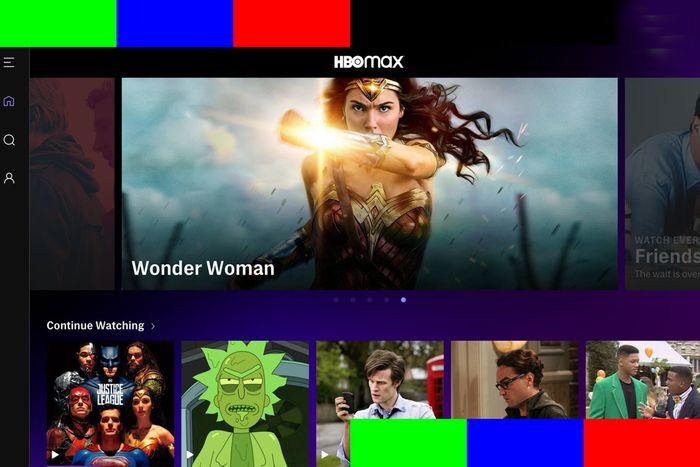

It’s hardly a disaster: Originals such as Love Life and Legendary, while not exactly dominating the pop-culture conversation, have gotten solid receptions from critics, and the Max user interface improves nicely on the already-solid HBO Now template on which it was built. Also, you can finally stream Friends again (or, if you’re me, every episode of Scooby-Doo.)

And yet right out of the gate, Max execs have found themselves hit with multiple hiccups:

• The platform freeze-out: While a last-minute deal with Comcast gave Max access to one of the country’s biggest cable and internet providers, the streamer is shockingly still not available on Roku and Amazon Fire. Those two companies dominate the standalone streaming-device market in the U.S., so not being part of those ecosystems is no small thing: At a time when there was a ton of free media hyping the launch of Max, millions of potential subscribers who’d heard about the platform were simply unable to sign up for the service. (It’s not hard to find folks on social media pissed off about this.) Sure, tens of millions of homes can still get Max through their smart-TV sets, video-game consoles, Apple TV, or Google’s Chromecast; cable companies such as Comcast are even integrating Max into proprietary platforms like Xfinity X1. It hasn’t crippled the new streamer. That said, Roku and Amazon’s decision to play hardball with WarnerMedia is costing Max, making it tougher to add new subscribers quickly.

• The name game: Despite valiant attempts before launch to explain it all to consumers (by both Max and media reporters like yours truly), the headache over the Many Faces of HBO (Max! Go! Now! Original Recipe! Cool Ranch!) remains a head-scratcher. It’s not that AT&T was wrong to connect the HBO brand to its big challenge to Netflix; that was logical, since HBO is the OG of subscription TV. The problem is that AT&T didn’t do what it now says it will do, i.e., get rid of HBO Go and make it clear that HBO Now is now HBO Max. There would’ve always been some amount of early consumer confusion as to the difference between Max and plain ol’ HBO. Having those other names just made things exponentially worse.

• Wind-ghazi: Turner Classic Movies has long put its showings of Gone with the Wind in context by having its hosts explain the movie’s many problematic aspects. But that curation initially didn’t extend to the movie’s presence on HBO Max, and when director John Ridley called out the platform in a Los Angeles Times op-ed, chaos ensued. The platform’s execs made the right call: They realized it was a mistake to have put the movie up without any mention of its racist elements, and decided to quickly make things right — perhaps too quickly. The movie was pulled, before Max could explain that it had no intention of permanently removing it from circulation, and once journalists and Twitter noticed, well … it was too late. The streamer put out a statement within hours of the first report noting that GWTW would be back soon with an appropriate and contextual introduction, but that’s an eternity in the age of Twitter. Right-wing snowflakes whining about cancel culture seized on a chance to bash Hollywood, while one of Max’s biggest assets — its deep library of classic movies — became a source of controversy rather than celebration. GWTW is back on Max as of yesterday, complete with a new intro, but the whole thing was a needless distraction. Max programmers should’ve addressed this before the service launched.

Buzz, but the wrong kind: Max execs surely would have preferred most month-one stories to revolve around critics kvelling over the comedic charm of Love Life, or the bold storytelling of reality competition Legendary, or even the eternal cuteness of Elmo’s late-night talk show. But it simply wasn’t to be: More digital ink was surely spilled about brand confusion and the merits of an 80-year-old movie than the platform’s creative output or how well the tech behind it worked. This is partially because of the (often unfortunate) feedback loop between social media and news media, where What the People Are Talking About on Twitter so often ends up becoming a news story.

But it also doesn’t help that the streaming world — including HBO Max — hides or delays releasing more concrete data, which could be used to establish better metrics for success. Back in the days when there were still new cable networks launching on a regular basis, reporters and media analysts could look at ratings to get a rough idea how a channel was performing. Streamers, however, almost never release viewership stats — and even when they do, they’re often not all that useful in determining actual audience size. And while most do report how many people have subscribed, they tend to only do so once every three months or so, usually during quarterly earnings calls. (Disney broke from that last rule by revealing day-one signups right away, and it was a smart move: The big number detracted from the platform’s early tech glitches and immediately helped shape the idea that the service was a success.)

This information gap means The Reporters Who Cover Streaming TV (if I can adapt a phrase from the great Lisa de Moraes) have been forced to improv when trying to assess how platforms are performing, particularly when said platforms are brand new and there’s little or no information about sign-ups and subscriber churn. Critics not loving an early batch of new programs and bored by the lack of library content becomes “Is Apple TV+ doomed?” America going gaga over Baby Yoda turns into “How smart are those Disney+ execs?!”

I’m exaggerating a bit here, of course, and I plead guilty to grabbing onto narratives about how a streamer is doing based on anecdotal evidence. Netflix’s recent decision to publish self-reported top-ten lists of movies and TV shows has been a brilliant marketing move since it instantly gives reporters a reason to justify writing about a title, as I did last week with Avatar: The Last Airbender. (Be sure to come back next week for my 1,000-word essay on Floor Is Lava, Netflix’s No. 1 show for much of the past week, at least per Netflix.)

Still, there’s a reason I started this week’s newsletter by calling Max’s first-month foibles “hiccups”: I think HBO Max is probably doing just fine right now. At least two of the three problems I listed earlier are not going to matter a lick to the platform’s long-term (or even near-term) success. Gone with the Wind is already back streaming and any blowback Max suffered from how it handled the temporary removal has already … blown over. The name thing could be an issue for a bit longer, especially if people still don’t grasp that HBO Max really is HBO with more stuff. But ultimately, I think everything resolves itself and most folks will simply come around to the notion that HBO outside of the cable world is now best accessed via the HBO Max app.

The Roku Rumble Continues

The one bit of launch-month heartburn that could turn into a headache for AT&T is the spat with Roku and Amazon Fire TV. Just this week, Roku upped the stakes by sending an email to users warning anyone who currently gets HBO via HBO Go that the app is going away at the end of July. Said letter conveniently leaves out the fact that WarnerMedia would be happy to let Roku users download HBO Max instead, nor does it mention that Roku is holding out for better financial terms. It’ll be interesting to see if consumers hold Roku and Amazon accountable or blame HBO Max if this drags on.

I’m also curious whether WarnerMedia fights back by launching the sort of education campaigns common whenever a cable company pulls (or threatens to pull) a TV network because of disagreements on distribution fees. One media exec this week told me he thinks many Roku and Fire TV users, who bought those devices with the understanding that they’d offer access to all the big platforms, would be furious if they realized HBO wasn’t the one playing hardball here. Will AT&T soon text millions of customers and tell them Roku is holding their HBO hostage? Might the company offer subscribers deeply discounted Apple TV units or free Google Chromecast devices so they can stream HBO Max? Or will WarnerMedia cave, realizing they need Roku (and Amazon’s) platforms more than they need a moral victory against Roku’s demands?

Rich Greenfield and his fellow media analysts over at Lightshed Partners are predicting the former is more likely. “This is an important and precedent-setting deal that will establish the power dynamics in a fairly nascent industry,” the company wrote on its blog this week. “The implications go beyond just HBO. We suspect AT&T is keenly aware and likely willing to be patient, even as it has a new brand.”

The long game: Indeed, even beyond the stand-off with Roku (and Amazon), AT&T knows success for HBO Max will be measured over the course of years not months. Fact is, it launched with a huge subscriber base — pushing 30 million — thanks to the decision to give HBO subscribers access to Max at no extra cost. Unlike Apple or Disney+ or [shudder] Quibi, it’s not starting from scratch building its streamer. AT&T needs to attract new subscribers, of course, to justify the billions in extra content on Max. But if new signups come in more slowly than expected, it won’t be a disaster, even if it won’t be ideal. Plus, the company can rightly note the coronavirus pandemic has deprived it of some key programming while the economic downturn could be making it harder to get new customers.

Expect the first real report card on HBO Max on July 23, when AT&T reports its second quarter earnings.