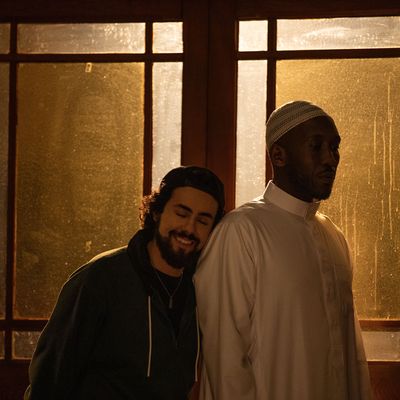

On the new season of Ramy, Mahershala Ali stars as the wise and charismatic Sheik Ali to a lost and confused Ramy Hassan, played by show creator Ramy Youssef. In an excerpt from A24’s quarterly zine, Youssef interviews his co-star about his relationship to Islam, refusing to do sex scenes, and how prayer factors into his acting.

Ramy Youssef: We’ve talked before about the spiritual struggles you had early on in your career over doing certain things you didn’t think you should do onscreen. How’d you come to terms with that?

Mahershala Ali: If you look at Judaism, Islam, maybe some versions of Buddhism, the Sikhs — any time anyone is hard-core practicing those faiths correctly, it feels like anything outside the faith is haram. But as you move further along, as you embrace the faith, get more comfortable in it and understand how you identify as a Muslim, you’re always examining your relationship to anything secular, anything outside of your actual faith. If you grow up Muslim, you probably have more of a natural barometer for what “slacking off” means for you — that middle ground where you’re okay not following something to the tee. Embracing the tenets of Islam that say you will be held accountable for all your actions, that you will be credited for all your positive actions, and you will essentially be called out on all the things you knowingly did wrong and all that, you begin to examine your work — entertainment, storytelling — and anything outside of your faith. And you have to strive to bring that into alignment with not just your religion, but with how your religion informs the way you see the world and what is okay and what is not okay, so that you can have peace.

I converted to Islam in my third year of grad school for acting, and then suddenly I’m being offered roles to play a god or a demigod. I’m six months into converting at this point, and I’m thinking about how the main thing in Islam is that there is no God but God, and Mohammed is his prophet, peace be upon him, but he’s a messenger, and God is God. And then suddenly I’m earning money playing characters that share power with God. It became really confusing for me, especially because then you see Muslims at the mosque and they’re like, “Saw you on TV last night.” Being a baby Muslim at the time, I was very literal about it as a working professional. I wasn’t compartmentalizing it in a way where I could be a little bit more empowered and say, “I’m not doing that type of thing anymore.” I can play a role that’s intimate, but do we need to be bumping and grinding? Can we take a more modest approach to that? I’m sure people have critiques about my decisions, but it was a way for me to figure out how to exist in this space so that I could do what my religion guides me to do, which is to take every aspect of your life and take it from darkness into light, or from a place of ignorance into a place of knowing.

In 2006 I was working with [David] Fincher on The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. I’d never done a movie before, and here I’m getting to work with one of the best directors in the world. There was this one scene where I said, “Well, I’ll do it on one condition. I just want to make sure that this is not a sex scene.” And so you see Taraji [P. Henson] and I come together, and we start to kiss, we fall down out of camera, and then it cuts. Before that, in 2002, I told the head of casting at Fox, a black woman, “I don’t do sex scenes.” And she’s like, “You’ll never work. You’ll never be a lead.” And what was great was I walked out of there feeling like, if I do then it’ll be evidence that God is real. I felt that way about it. I didn’t say that to her, but it didn’t shake me.

And now you could call her and be like, “Well guess what? I got to be on Ramy.”

Yes [laughs]. Which I’m so excited about, by the way. I gotta say, for the time that we’re in, it really leaves you with something you get to sit on and think about. A Buddhist, a Christian, an atheist, an agnostic can all watch that and have some real thoughts about the world and what they’re doing as individuals — as a result of being entertained for 26 minutes, watching your show.

InshAllah, man.

InshAllah.

When I moved to L.A., the mosque was my spot. That’s how I met people. And you found out about Islam at a mosque in Pennsylvania, in Philly. What does it feel like now? Not to gas you up, but you’re Mahershala Ali, you can’t really walk into the mosque in the same way anymore.

It’s weird because we put so much emphasis on equality in Islam, right? Everybody being equal, no ego. But the nature of our job means there’s a camera on us and everything we do. We’re not following a car salesman around and being like, “Nuh-uh, you hugged that woman.” So there’s a reaction coming from the community of people who love and pray for you, and who are challenged to follow the same tenets as you. More and more these days, I find myself reacting to that in a way that can almost be abrasive. People will come up to me at the mosque like, “Oh, brother, can we take a pic?”

You’re in the prayer space and someone’s taking a photo of you during the prayers.

During Jummah! During the Khutbah, sometimes. And I’m like, “Whoa, this is my safest space.” But the flip side of it is, as Muslim actors and storytellers, we’ve never had the opportunity to participate in any of this commercial stuff, any of the images and the messages and the comedy, the jokes, the drama. We’re always being hired to go blow something up, to be caught, you know? Once our communities begin to see us in there really having an impact, people can’t help but be excited — and that’s no diss or anything, because again, those are people who are praying for my family, myself, and my well-being — but it changes your relationship to the space itself. I find myself going to Jummah and leaving Jummah. I won’t hang as much because the conversation goes so quickly to work, and “I saw you on something.” I respect it, but I found that as an introvert, it makes me way more introverted. In those conversations, I find myself being less present because I’m so much more protected.

At this point in my career I have a smaller set of eyes on me, but that set of eyes is the mosque demo. I remember I was at Friday prayer right after the show came out, and I’m sitting there listening to the Imam speak, and I notice that people are looking at me. And this isn’t me just thinking about it in my head — people are literally whispering. When the Imam finishes talking, someone turns me like, “Yo, can we take a photo?” So then I start feeling like, does my presence throw off the spiritual experience of somebody else? Again — not trying to have an ego about it, but this space that meant so much to me for so many years, I’m wondering now if I should be going there? And that’s a really weird place to land.

As you talk, it makes me think that for a Muslim there’s no status that takes you beyond the community and the instructions. So the answer must be that as uncomfortable as it is for you or me or whoever, your presence is important for the other people there because then they have to go back and deal with, hey wait a minute, what was the Khutbah today again? What you lose with the loss of your anonymity is some of the quiet and the reflectiveness that happens when you go to the mosque for 45 minutes. That gets cut down to, all right, I’m doing my Sunnahs, now it’s the Khutbah, then you’re dapping people up and you’re out of there. The only thing is to find a home for yourself, a mosque you always go to. The awe relaxes a little bit because people meet you six, seven times, and at a certain point they’re like, “Oh, he’s just a regular dude.” And then they’re disappointed that you’re just a regular dude, and I’ll live in that place.

And then they’re like, “Oh, he’s shorter than I thought he was.” And you’re like “Aww, come on, man.” [Laughs.]

We talked a little bit about this before, but it is not enjoyable to be humbled. It is not.

The interesting thing to me, too, is the way you deal with how your life has changed — not only in a public-facing way, but how when you walk onto a set now there’s a different expectation. How does your spiritual practice and your faith keep you going so you don’t go crazy with all that, especially when you’re on the job? Are you praying in your trailer?

There’s more fear and anxiety, naturally, but I find that after, there is recognition and the expectations change and people are watching you, your defense is prepared for you, so to speak. It’s like, if you have a great rookie season, they’re out there ready for you.

You’re a stand-up. I’m sure you’ve always been afraid. And then the lights come up when you get onstage, you get the mic in your hand, adrenaline takes over, and then you’re addicted. As afraid as you might be offstage, you still got that little hit you need from the last time you went up there — whether you bombed or it went great, there’s still the rush. I’m very measured and thoughtful about the things that I commit to doing. It doesn’t mean I only commit to doing things I know I can do. If anything, I always do things I’m not sure I can do. I wasn’t sure about the character for this season [of Ramy], Sheikh Ali, but that’s when I know I’m in a good place. When I’m a little nervous, that’s what I should be working on.

My point, in answering this question in a really long wordy way, is to say that it puts the emphasis back on Allah for me, because I’m like, “I don’t know how to do this, and I’m scared, and Ramy is really ready to go for this scene, and we rewrote this joint and I’m super nervous right now”… The fear and anxiety increases, but your confidence should also have increased as well. When you’ve got more space to make decisions, you probably have more of everything else, too. It’s made me slower. It’s made me more conscious. I’ve always been in prayer on every set. I don’t think I’ve ever done a scene in my life and not prayed real quick, even just an audition.

If you’re talking to young actors who are trying to figure out what method they should do, Stanislavski or whatever, you would probably just say Islam would be the key one to practice.

It’s so funny. Honestly, I don’t do anything without praying. I’ve been in press runs from Green Book to Moonlight and they’re like, “So how’d you prepare?” And I might be saying, “Yeah, I did this, that, and the other. I studied this, I read that, I made the mixtape.” And to keep it way real with you, I just prayed, bro, that’s all I did. Honestly, I’m like, “God, help me make this real.” And that’s it. That’s what I do. That’s my technique.

This interview has been edited and condensed.