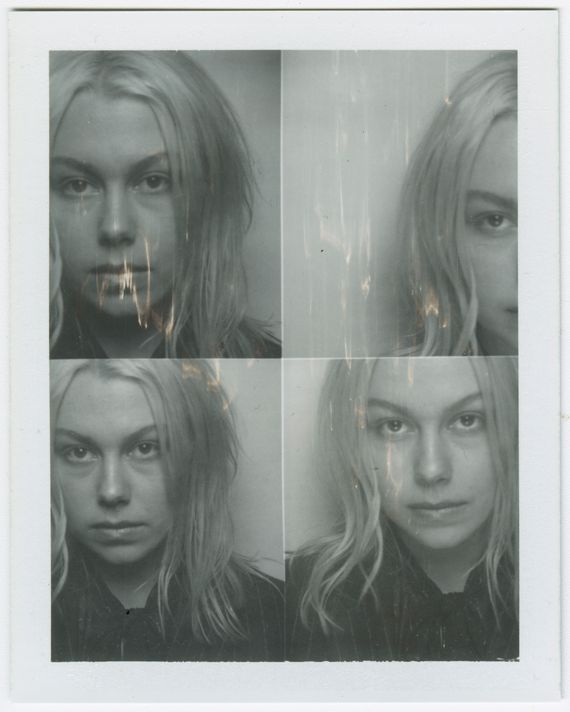

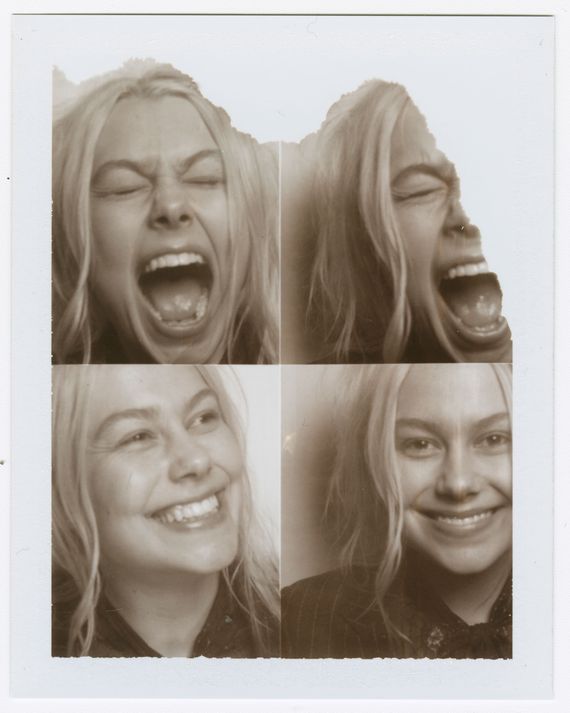

“Is this a ghost piano?” Phoebe Bridgers asks, eyes and mouth gaping at a mahogany pianoforte. The increasingly prolific singer-songwriter loves a good scare. Back in February, we met at a haunted New York City landmark, the Merchant’s House Museum between Greenwich Village and Noho, to discuss Bridgers’s sophomore album, Punisher. Even pre-coronavirus, it seemed odd to be hunting the paranormal in broad daylight, but we’ve since had to stretch our ideas of normality. (Was there ever a “normal”?) The museum — an old-school, brick rowhouse — didn’t exactly scream “boo” from the exterior; it’s nestled in downtown Manhattan. But the Tredwells, a wealthy merchant family who lived in this home for nearly 100 years, may have never left, exactly. At the time of our visit, the pandemic was looming but hadn’t halted the music industry — or the world — yet.

Bridgers was set to open for The 1975 on tour and embark on a run of solo shows. Everything has changed since then. Bridgers released Punisher earlier than expected in June amid even further crisis as a string of recent cases of police brutality against black people have sparked the latest Black Lives Matter uprising. Instead of arenas and clubs, a June tour took place in her bathroom and bed. Bridgers has had to adapt like the rest of us.

Since the release of her 2017 debut album Stranger in the Alps, Bridgers, 25, has been lauded for everything from her tender crooning about sexting and loneliness (“Demi Moore”) to her frank observations on death and depression (“Funeral”) and arresting breakup anthems (“I See You”). Her goofy-yet-earnest, emotionally accessible songwriting has led her to share stages and studios with the indie elite across generations, including Bon Iver, The National, and Julien Baker; she recently landed four features on the new 1975 album Notes on a Conditional Form. Following her debut album, the Pasadena native refused to slow down. When she wasn’t on the road, she leaned into collaborative side projects: indie-rock supergroup boygenius with Baker and musician Lucy Dacus and Better Oblivion Community Center with Bright Eyes leader Conor Oberst.

Three years since her debut, Bridgers has returned with a head rush of personal growth, loss, and catharsis in Punisher. Where Stranger in the Alps focused on desire and depression, her sophomore record analyzes the life events that fed that record, hedged of course with her brand of levity. “Punisher is me still revisiting some of the shit I was traumatized by,” she says. The allure of Bridgers has come from the insecurities and intimate, coming-of-age snapshots she re-creates in her songwriting. Bridgers’s familiar, exhilarating harmonies about intense heartbreak resurface, but Punisher allows fans a deeper gaze into her psyche.

While roaming the city’s haunted house, our conversation was raw, unfiltered, and tearful. We never saw the Tredwells’ ghosts — just revisited Bridgers’s own.

You chose “Garden Song” as the introduction to Punisher, but it doesn’t necessarily jump out as a typical “lead single.”

Something about it mirrored the first record. I released “Smoke Signals” first on the first album, there’s nothing “single-y” about it. I’m not less proud of it, but it is less radio, and I didn’t want people to think I made a radio album. There are some songs that are a more obvious choice for a single, but I like keeping the ball in my court as far as what genre I am. I feel like it represents the record a little bit more. The more uptempo songs, those are outliers.

I was more immediately drawn to “Chinese Satellite,” for the unwavering hope in its lyrics.

That’s the first I’ve heard that, so I’m glad. It’s about jogging. I don’t run, really, because I have bad knees, but this was about trying to run, and then the idea that you’re pretending to be a person and just how hard everyday shit is. It goes back to my love of Harry Potter: it’s basically about the feeling of not getting a Hogwarts letter, where you’re waiting for someone to save you from the monotony of every day life. I feel like some people think about that with antidepressants — “My life started when I started taking them” or, “My life started when I started doing yoga.” And I’m just waiting for my thing that makes every day different. And magic and aliens.

I’ve been feeling in a similar funk, and I’m waiting for —

Something?

Exactly.

When my fucking dog died at the beginning of last year, I had [my emotions] in all day. And then I went into therapy, and I didn’t like my therapist. I was like, “This is going to be lame.” And I closed the door and burst into fucking tears. Then a year later, I went to a better therapist. We were talking about childhood trauma and shit, and then she mentioned my dog, and I was inconsolable for a half hour.

I just sobbed for five days in a row, constantly. I’ve never had to put an animal down as an adult until now. It’s a weird thing.

It’s all you think about. It’s all I think about because I feel genuinely dissociated from my life, good or bad, all the time. My best friend, Emily, her dog died the same week, and so we went and got tattoos. It’s the first time I’ve ever moved through life without him. I don’t know how to be an adult without him. It’s so hard. I can count on my thumbs the times that I’ve cried in the past couple of years about other shit, but every time I fucking think about him [I get emotional]. The album is dedicated to him.

It’s not a concept album, but looking back, the first record was about my life up to that point. It is all me wanting things and wishing for things and feeling depressed and feeling without in my life, in my soul. The second record is me still revisiting some of those themes [but] completely over some of the shit I was traumatized by, and [being] more interested in other stuff, like the person I am now. Some of it is disassociation, and also, like, no matter how tight your life is, mental health can creep in and fuck with you at any moment. Maybe it’s a theme of starting therapy. Because even though I have what I wanted, like I talk about in “Garden Song,” that [trauma] doesn’t just go away when you get where you want. You have to deal with it anyway.

You often get lumped into this “sad girl rock” category with artists like Soccer Mommy and Julien Baker. How would you identify your sound?

Well, it’s definitely sad music. But I think there’s just a fine line between [that and] a sad girl, tongue face. Sometimes people will come up to me and be like, “Oh, my God. I’m so fucking depressed. Ha ha ha ha ha.” And I’m like, “Are you okay?” The conversations I want to have are like, “Can we all heal?” But I’m also flattered because my favorite music is lumped into those genres, like Julien [Baker], Soccer Mommy, Bright Eyes, and Elliott Smith. It’s as if it’s a fashion statement and not literally a mental illness. But again, I know that we are all in the “scene,” and I’m sure there are shoegaze bands that sing about dumb shit that struggle with the same stuff. It’s just we talk about it more explicitly.

I don’t think [what we’re doing] is saving the world or anything, but I’m always relieved when art is real and telling the truth. Things that mean a lot to me are perspectives I’ve never heard before, which inherently is whoever’s talking about their personal experience. My friend Haley Dahl, who’s in a band called Sloppy Jane, did this insane interview that I read where she was like, “Tell the truth because otherwise, if you lie, you’ll have to create each reality and keep track of what you are and aren’t allowed to do, or say to who or not say to someone.” I just want to make stuff that’s true.

Last year you shared your account of emotional abuse and sexual misconduct at the hands of your ex-boyfriend and former collaborator Ryan Adams in a New York Times investigation. But the circumstances you shared in the piece were kind of hiding in plain sight in the song “Motion Sickness” on your first album. What’s your relationship with that song like now?

That song hasn’t really changed other than I feel a little bit more like “Fuck yeah, girl” applause [from the crowd] when I play it sometimes, instead of just a funny [reaction to a] song about a shitty ex. It’s weird because I forget that people take it seriously now. I used to play it live and be like, “This song is about Ryan Adams. He hates women.” And people thought it was funny. I thought it was a funny thing to say. So then, weirdly after the article came out, I was playing the same song, making the same “jokes.” [It’s become a] thing in Japan where everybody wants the record signed. Someone brought [me] the 7-inch that Ryan produced. It’s like, alright, funny. And then I started signing it. He’s kind of older, and he’s pointing at it and he was like, “We stand with you.” I literally was like, “Oh my fucking God.”

Wow. That relief of finally being taken seriously.

I just had been dealing with it and talking about it with my friends. I didn’t have some crazy secret. The weirdest thing was discovering the world that he created for other women. I didn’t know how many, and I didn’t know the extent of the damage, so that was super emotional. But I feel like I had been talking about him just being an asshole, so much that when it came out, people would put their hand on my shoulder and be like, “Hey, are you okay?” It took me by surprise.

There’s this idea that we’re somehow in a post–Me Too world, but music has yet to have its full reckoning. R. Kelly could very well work again and Dr. Luke’s still producing music under a pseudonym. How do you feel about it now on a macro level? The emotional cost and labor of being a so-called silence breaker in an industry designed to tune women’s voices out.

I feel fucking exhausted. Everybody feels exhausted. Not even just being someone who’s spoken out, just keeping track of shit. Like who can I talk to? Who can I not talk to? Oh, we don’t like that band anymore. Is it legitimate, or is it just a weird fluke of someone talking shit? The fact that not very many journalists have dug in and done true research means that I end up reading about a lot of stuff on blogs that is just one person talking and then I feel so confused all the time. It’s exhausting, but it also means progress to me that we’re all like, “Wait, nobody hire that person, because they’re fucking horrible.” Everybody has to fucking look out for each other. It’s like, let’s save the next person who hasn’t been warned. I wasn’t fucking warned, but then I went into the world and started playing music, and people were like, “Oh yeah, of course that happened.”

Do you dread Ryan’s inevitable comeback?

I don’t, I don’t at all. It’s just like being with a group of people who participated in that … whatever dude. There is a part of me that feels bad for him. A part of me that is separate from myself, that’s empathetic at all. I’m just like, “Man, you had a chance to be so cool, and you fucked it up.” I don’t fear it at all. If it happens I’ll be surrounded by people I love and people who are like, “This sucks.”

As your fan base has grown, so has your inner circle. How has your relationship with yourself and others evolved?

[I’ve become] a touring musician, which I wasn’t when I wrote the first record — a person who is always traveling, a person who still has a hard time being by themselves and ends up in codependent, weird shit. And even though I feel like an independent person, I end up in relationship dynamics where I need to fix people. I need to be around people who don’t believe in me because, otherwise, I’m afraid I’ll get a big head or something.

Fame is bizarre.

This is not all my friends. I love my fucking friends, and they’re so supportive for the most part. But every once in a while someone gets in romantically or friendship-wise where I’m like, What?! But I’m fine. Why do I need this person to tell me that I’m bad? It’s a weird sub/dom emotional thing where I need someone to hate me so that I don’t feel stuck up.

Later in May

Being in quarantine has forced us all to spend time with ourselves and changed everyone’s plans. How have you been personally affected?

Well, no tour, which is fucking depressing. Other than that kind of nothing. I’m doing the same interviews and stuff just from my house. I guess people have been pushing releases, and I chose not to because I conveniently have everything kind of done, like music videos and stuff. But it is depressing. I miss my life so much.

One of the highlights, at least for me, was watching you and Normal People star Paul Mescal have a livestream chat after he included you on a Spotify playlist of songs that inspired his character, Connell.

He, I guess, had sent me a message forever ago and then deleted it cause it was embarrassing. And then I watched the show and started talking about him and then people started tagging me in interviews where he talks about me. Then we became like internet homies, and now he’s my internet crush. [Normal People] definitely destroyed me, but it has been nice. Talking to Paul made it more palatable for me to not be super depressed after watching it cause it’s so sad and then he’s like a happy normal dude.

Have you struggled to remain creative, or have you found yourself being productive in some way?

No, it’s really hard to stay creative. It’s hard to even function like a normal human being, basically. I’m trying to take it every day at a time.

Your music is so cathartic for so many people. Have you thought about the timeliness of the record? Does it feel better or worse?

I mean, it definitely feels worse, but it feels good to have something out. I think everybody is living through the worst time in their lives, individually and collectively. But I am glad I have something to focus on. Even Bright Eyes’ new stuff has been more prescient and more relevant. Everything is becoming more relevant right now, and my music definitely isn’t exempt from that. It’s happening to all of us.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.