In Netflix’s Dead to Me, Linda Cardellini has to cry. A lot. You would cry too, if, like her character, Judy Hale, you: (1) committed a hit-and-run and covered it up, (2) befriended the widowed woman of the guy you killed, and then (3) helped that widowed woman hide your ex-fiancé’s body after she killed him in what she claimed was self-defense but was in fact less “self-defense” and more “bludgeoned in a primal rage,” which is considerably more murder-y. Not to mention reconnecting with your emotionally manipulative mother while she’s in prison, and also falling for a cute girl who just so happens to be the ex-girlfriend and current roommate of the detective investigating your hit-and-run.

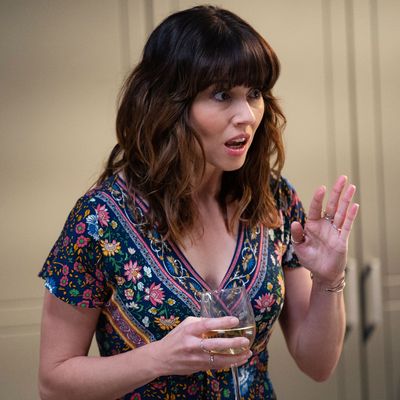

“Acting-wise, it’s a really athletic role,” Cardellini says. “It’s challenging in every way, in terms of the trauma of it, the drama of it, the comedy of it, and flipping back and forth. I get to do so many different things within this character, and the character is so different from who you think she’s going to be when you meet her in the first episode.”

To better understand how Cardellini tapped into that challenge, we picked five of Judy’s juiciest scenes from Dead to Me season two, and she graciously broke down the process behind her performance in each one.

In the scene that opens the fourth episode, Jen and Judy drive home from burying Steve’s body. They oscillate from nervous banter about being thirsty, to distressed panic about how they may have left a cell phone in the hole with Steve’s corpse, to outright dread when a police officer pulls them over and says, “You committed a crime.”

We don’t have very much rehearsal at all. We run the words and then we get in there and do it. You’re shooting from so many different angles, so you pick up what works as you go along. You pick up a response from the directors and everyone on set of what works and what’s funny. Christina [Applegate] and I just feel it. So with the drinking of the water, I was really gulping it loudly and then I’d do it a little less, and sometimes we turn the meter up and go broad. You get to explore different ways of doing it. We really trust everyone in the editing process as well to make it seem smooth.

It always feels like the world is about to crash in on [Jen and Judy], so it needs to operate in that high intensity for them, but you get these moments for relief with banter. That is what allows you to take a breath within the tension. If you’re sitting there with your best friend, what is going back and forth between you before the other shoe drops? When you have these moments of large emotions, there is something that comes along and breaks it up for a second. Even when [Jen’s] like, “My phone! My phone!” The idea of that being broken up by, “Oh! I found it.” It doesn’t stay too dramatic for too long, and I think that’s how life is; you have to do something to grab yourself out of it.

There’s tons of improvising on our show. At the end of that scene, when we get pulled over and we’re talking about being berry foragers, Liz [Feldman] was like, “Go ahead and keep talking until it gets to the window.” And then she’ll call out, “The berries work — go with that! The trees work — go with that!”

Later in that same episode, Jen and Judy crash a wedding (for the open bar, naturally), and Jen suggests that Judy take a moment to say something about Steve. Judy delivers a spontaneous eulogy that reveals so much of herself, meanwhile Jen is trapped with her secret — that she didn’t really kill Steve in self-defense — and the frisson of dishonesty beneath their friendship gives an edge to their vulnerable exchange.

It was a really difficult scene. It’s a lot of dialogue, coupled with a lot of emotion, and also we’re just sitting there. Keeping that intensity up for all of the different angles we shot it on, it’s always a challenge because the emotions are so high. When we’re doing a scene like that, where you have to have that emotion raw in every take, they are easily the most challenging. They’re exhausting.

I don’t think [Judy’s] ever really had a moment to talk about what [Steve] meant to her in a good way. Even though that relationship is really unhealthy, to her, as someone who is in this relationship that’s toxic, there has to be something good about him. And I think it’s important to see that duality in that relationship. She knows that he was toxic, but at the same time, he also made her feel very special, and that is what made her stay. She says he’s the first person who ever made her feel special, but he also made her feel the most terrible she’s ever felt in her life. It would be easy to tell her not to mourn, but that’s not who she is. I think that relationship is really complicated, and I think there were things that she truly loved about him.

But the moment where the guy comes up and asks them to dance while Judy is crying and baring her soul and unraveling this complicated relationship — because he’s clearly not reading the room, fucko! — Jen protecting her is something that Judy’s heart sparks to because she’s never had that in her life. She loves Jen’s ability to be angry and stand up to somebody, because she can’t. When he walks away, Judy is still like, “Poor guy!” She feels bad for him, and Jen doesn’t. That quality is aspirational in Judy because she has a hard time doing what Jen does easily. Jen protects her heart at that moment and says to her, “I’ll be your person. Will you be my person?” And that is all Judy wants to be.

As the character, I try to really listen when Jen is talking to Judy. She really is looking for these morsels of love from people. So when Jen says something about Judy being the kindest person in the world, that is the most enormous compliment to Judy because she knows she could’ve turned out to be someone like her mother. Deep down, she is afraid of that — she is afraid of becoming someone who doesn’t care enough about other people’s feelings. I shake my head no, because she can’t really accept it — because that’s too big of a compliment, and she feels so much shame for herself. And then they become each other’s person. Judy in that moment gets to have a breakthrough. She gets to talk about what happened with Steve. She gets to say, “I know it’s not right to feel this way, but I feel this way.” And she gets to have a friend to lean on.

And in true Dead to Me fashion, Jen has a huge secret that mirrors Judy’s secret from the first season! That’s the brilliance of how the writers weave things together. The characters have these wins, but they are always shadowed by these secrets and lies.

Judy gets a glimmer of happiness at the end of episode six, when she has a fantastic time with all her favorite people at the arcade and spends the night with Michelle (Natalie Morales). Feeling all post-sex-glowy in the opening scene of episode seven, she floats into the kitchen but then turns around to discover that Michelle’s ex turned roommate is … Detective Ana Perez (Diana Maria Riva), who is all kinds of suspicious about Judy and is extremely not happy to see her.

I love just saying “oh fuck” under my breath. Judy is trying to have a smile on her face, but she is in deep shit at that moment. The idea that Judy has this relationship with Michelle is such a breath of fresh air, and it’s a look at what she could have if she could be free of all the terrible things that have happened to her with murdering people. That’s coming off the heels of the night before, when they’re all having a good time at the arcade. She wakes up and says “I love you”; she goes into the kitchen feeling happier than you’ve seen her in two seasons; and she is confronted with that death stare in the kitchen. Judy is forced to wither under that stare for two minutes, and she can’t wipe off the smile from the night before.

And Diana is so wonderful. I love what you get to see about her character in the second season, because you think you really know who this character is, and she’s so much more than that. I love the relationship our two characters have. The idea of Judy being under that character’s gaze, Judy giving her a compliment on that T-shirt. She’s always trying to accommodate! She knows that’s how people let you in. She’s a little bit like a vampire that way.

In the ninth episode, Jen’s secret finally comes out. Judy thinks she’s about to deliver the worst news — that the police have enough to pin Steve’s death on Charlie — so she’s decided that she should take the fall. But as she’s making this declaration of self-sacrifice, Jen blurts out the truth: She didn’t murder Steve to save her own life. He said something cruel, and she lashed out and attacked him while he was walking away. In the argument that follows, Jen spits out that Judy is only willing to forgive her for this horrible transgression because she’s so desperate for love she’ll take anything from anyone. Judy leaves the house in tears, refuses to do or say anything to hurt Jen, and instead punches her own chest and screams into the night.

For me, the scene is terribly painful and incredibly emotional. There’s so much that happens. There’s me coming and talking about Charlie, then there’s “What are we going to do about it?,” and then there’s me confessing that I nearly killed myself, so I owe it to her to turn myself in. In a typical show, you might have a scene about each of those. We’re doing it in the span of a few minutes. And then Jen has to tell me her truth, which she’s been trying to tell me but couldn’t. That is her act of confession and kindness, but it’s followed up with something incredibly damaging to Judy: that she thinks she’ll love anybody because she’s desperate. It’s a terribly mean thing for Judy to have to digest. But during all of that, I also feel sorry for Jen.

When I walk into that scene, I’m walking in with the most horrible news I can imagine: They’re going to arrest Charlie. That’s the worst thing that can happen to Judy and Jen; they’ve decided they’re going to protect these children at all costs. When she walks in with that, it’s already at an 11 for her. She knows Jen is going to tell her not to do it, but she’s going to jump on the grenade because that’s her karma.

While this is happening, the person she cares the most about is changing before her eyes, because she finds out that Jen has been lying to her for so long. The two people who were her person are gone in that moment: Steve is gone, and Jen, as she knew her, is gone.

But then she has this moment of clarity because she realizes that how Steve made her feel — the emotionally abusive way he treated her — is probably what he did to Jen, and it’s not Jen’s fault. So she immediately goes back to Jen’s side. Judy sees everything as her fault. She carries this shame; she carries this guilt and the stress. You see that come out when she leaves the house and she takes it out on herself. She has this secret self-harm that she does, and it’s her trying to get this poisonous feeling out of her.

Judy is very accustomed to saying sorry. Jen, less so. Jen wants to deal with it by having Judy hit her and doing something physical, and Judy is sitting at the wheel of the car saying, “Please move, please move,” because the worst thing for Judy is hurting anybody, which is reminiscent of the whole reason this story exists, because Judy hit Ted with her car. Judy would never hurt somebody on purpose. Instead, when faced with somebody who just said this terribly hurtful thing to her, she’ll take it out on herself.

I didn’t practice [the scream], so when it came out, it just sounded like that. The great thing about playing those scenes is that my body is engaged, even though it’s a lot of dialogue and emotion, because it’s operating at this level where something is about to burst. There’s this physicality I wanted to get myself into by making my body almost feel like it’s buzzing, so there’s this energy shaking within her. That scream felt really good because she’s keeping so much in, and after that scream, she has nothing else to do but punish herself. To me, it was a natural progression of how Judy deals with her feelings.

The scream is really rare for Judy. You don’t ever see her yell. I know there has to be a certain level that she has to get to to get it to come out of my body. Everything in that scream is about getting my body to arc toward that place, to get it into my muscles and let it come out, but still having that poison left so she hits herself.

In the season finale, Judy visits her mother, Eleanor (Katey Sagal), in prison to tell her that she doesn’t have the money for a lawyer. But her mom pivots to asking for a deeper favor: Would she write a letter to the parole board telling them how much she’s changed? It’s proof that Eleanor will always manipulate her, refuse to take responsibility for the pain she’s caused, and will never be the person Judy wants or needs. Judy, having internalized Jen’s advice about needing to learn to say no, refuses to do what her mother requests.

It is high stakes because this is the person who has crafted her whole identity. She has longed for that mother-daughter relationship, that idea of family. She thinks she’s going to go in there and say, “Sorry, Mom. I couldn’t get the money,” which is a big deal for her. I think she feels accomplished by saying that, but there’s a little bit of an excuse built into that first no. When the second no comes, she really has to screw up her courage because her mother is asking her to do something for her, and Judy’s knee-jerk reaction is to say yes. The idea of saying no and telling her why — and the why being that she hasn’t changed — that is huge for her. She could have never done that without Jen’s friendship. It’s Judy coming into her own, and it’s reaffirming how essential the friendship is.

When her mom first says “I’m sorry,” Judy hears that and takes that in … but it’s followed up with “… but you were a hard baby and because of that, I had to do drugs.” Poor Judy! She never gets the recognition she wants from her mother, so she feels very guilty and lonely and sad. In the moment when she says, “No, you haven’t changed. It is you; it’s not me. I was just a child,” she forgives herself for some of the mistakes she made with her mother.

I didn’t go big with that “no.” I felt it was most powerful if it was almost casual, you know? I wanted it to be something that the audience knows is a moment, but Judy isn’t making a moment out of it. If you’ve been following the show, you know how much that “no” means. She doesn’t have to scream it because the act of saying it is the power that she holds.