What’s your favorite movie meal?

Perhaps it’s the opening feast from Eat Drink Man Woman. Maybe it’s Reynolds Woodcock’s “hungry boy” breakfast in Phantom Thread. Or could it be the spectacular timpano from Big Night?

Compared to those feats of onscreen decadence, the oily cakes from Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow are a more modest affair — a simple batter, fried in fat, then topped with a pinch of cinnamon and a spattering of honey. The secret ingredient is milk; in this case, milk that our heroes have surreptitiously purloined from the first cow to arrive in 19th-century Oregon. The addition of stolen dairy makes the oily cakes not just criminal, but also criminally delicious. They sell, well, like hotcakes. But can our pioneer protagonists fry enough to make their fortunes before frontier justice catches up to them?

I won’t spoil (heh) the ending, but I will say this: Thanks to the combined efforts of the movie’s props department, who gave the oily cakes their ideal ochre crunch; the sound team, who came up with the perfect oily sizzle; and the actors, who receive each mouthful with rapturous bliss, First Cow has given us the most appetizing onscreen dish in recent memory. Upon finishing the movie, I knew I simply must taste them.

And so, since I’m the person who does that sort of thing around here, shortly before First Cow’s theatrical release in March, I emailed A24 asking for the oily cake recipe. They obliged. (I found out later they’d also given it to another journalist, but we’ll get back to that.) Then the shutdown happened. I went to my parents’ house, where I spent three months not making the oily cakes, for fear of burning the place down. Then I went back to the city, where I spent a few more weeks also not making the oily cakes, because the nice family upstairs has dogs and small children, and I didn’t want to endanger them, either. But now, with First Cow out on VOD, and my neighbors out of town, there were no more excuses. It was time to try my hand at deep-frying.

What Are in the Oily Cakes?

A24 provided me with a basic list of ingredients and proportions: milk, flour, active dry yeast, butter, eggs, sugar, and salt, plus lard for frying. So far, so simple: Everything was period appropriate (except the yeast, which was standing in for pâte à choux) and readily available at my local Key Foods. However, I quickly ran into my first hurdle: They did not actually tell me what to do with any of these ingredients.

I wasn’t completely on my own. Actor John Magaro — who actually did his own fry-work — gave me some helpful advice. “Don’t get your oil too hot.” he said.” When you throw in the dough, you want a light bubbling around the edges. You don’t want it to be like a volcano going crazy, otherwise you’re going to burn it real quick.” But, he said, I’d probably be fine. “Make sure you have the right ratio of the ingredients, and the rest is pretty simple.” Personally, I was less confident.

How hot was too hot? The movie’s PR rep provided a range: Try to keep the oil between 355 degrees and 370 degrees. “Don’t let it drop below 350 degrees or they’ll get greasy,” they warned. (They advised using a candy thermometer, as the crew did; the commitment to period methods only went so far.) So: not too hot, and not too cold. I had a real Goldilocks situation on my hands.

As for the rest, since the oily cakes were basically rudimentary donut-holes, I figured a donut recipe would do. I turned to the nearest one I had on hand, which turned out to be Ruby Bhogal’s. After adjusting for my ingredients, it was time to oil up those cakes!

Day One

The first thing I did was get renter’s insurance. Just kidding! The real first thing I did was dump all of the fat into my Dutch oven so that it became a literal bucket of lard.

Here’s something they don’t tell you about lard: When you heat it up, it fills your kitchen — or, if you live in a studio like I do, your entire apartment — with a distinctive barnyard aroma. The smell can be polarizing; I was transported back to dreamy memories of childhood field trips, but my girlfriend had to flee the building, muttering, “The smell of pork haunts my soul.” If for some reason this does not sound appealing to you, vegetable oil will work, too.

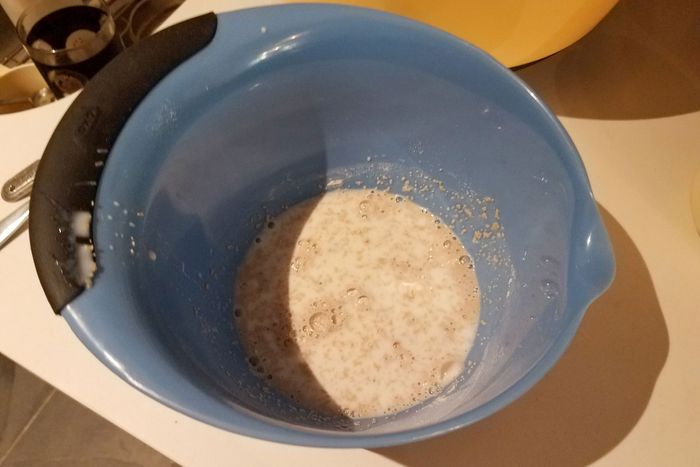

I’d been told that the filmmakers had the most success with a “quick-rise” technique with the yeast, which hopefully means I did the next bit right. In a small mixing bowl, I added the active dry yeast, one tablespoon of sugar, and one tablespoon of flour. After warming up the milk in a saucepan, I added it to the yeast mixture, then covered the bowl with a tea towel and waited ten minutes.

From there it seemed simple: Mix the dry ingredients together, then add the wet ones, then finally add the yeasty mixture. I stirred to combine, then let it prove again for ten minutes. This is what I got:

A dry, heavy, lump of dough that looked absolutely nothing like the batter in the movie. But, working off the assumption that everything gets more appetizing once you dump it in hot oil, I decided to press on.

By now the lard was fully liquefied. I turned the heat up to high, and got it to that 355 degree to 370 degree sweet spot. I set up my frying station. It was time for the rubber (in this case, absurdly tough dough) to meet the road (extremely hot lard).

The first batch went in, and I got the instant gratification of seeing the lard erupt into light bubbles, just as Magaro had promised.

After diligently swirling the oily cakes to make sure they were evenly cooked, I examined the first batch. The verdict: not good. They were crusty and craggy — more like deep-fried scones. I’m sure to a certain segment of Great Britain that sounds divine, but that was not the assignment. Could this dough be salvaged?

Since dryness was the chef offense, I added a few tablespoons of water to the mix. Voila! The batter got softer and more pliable, and the cakes puffed up into delectable round orbs.

How did the first draft of oily cakes turn out? They certainly looked amazing, so golden-brown the Stranglers themselves might be impressed. But that beautiful batch was also slightly underdone in the center. (I imagined an extremely tan man frowning and saying, “That’s raw dough.”) So back into the bath they went. A few minutes in the lard was enough to get the oily cakes a nice brown exterior, and a fully cooked inside.

Still, they weren’t there yet. Magaro had advised me that the oily cakes should taste more like beignets than donuts. (He also informed me that the fresh ones on set were “really good,” and that poor Toby Jones once had to spend a whole day eating cold ones, which were less good.) Mine weren’t close to that; they were denser, closer to a hush-puppy texture.

It was then that I discovered that the recipe I’d been given was slightly different than the one the filmmakers had given Slate. Mine called for one and ⅛ cup of milk; the other for one and ½, plus a little more water. Was this a mistake, or some sort of fun experiment A24 was playing on America’s entertainment journalists? I’m still not sure. But I did know that those ones looked significantly more like the oily cakes in the film. Unfortunately, it was getting late: Like a pre-cancellation Claire Saffitz, I would have to continue with this assignment for a second day.

Day Two

For the second day, I decided to make a few big changes. More milk, obviously. Following Magaro’s lead, I also decided to work off a beignet recipe, namely this one from Alexandra Penfold. And, for the sake of my girlfriend, who was trapped inside with me on a rainy Saturday, I chose to forego the lard this time and use vegetable oil for frying instead.

I’m happy to report that day two went much better! The milkier dough came together a lot easier — it was soft, stretchy, and slightly gluey. When the batter hit the oil, my apartment was filled with the unmistakable aroma of funnel cake, one of the food world’s top ten smells.

Texture-wise, too, I got what I wanted: crispy cracklings on the outside, with a delicate, pillowy interior. I was pleased to know that my favorite movie of the year was not based on a false premise: Milk really was the key ingredient after all!

These oily cakes were also not as sweet than I expected, but as Don Draper might say, that’s what the honey’s for.

Would I pay 10 silver ingots for one? That’s not important. The important question is, would you?

How to Make the First Cow Oily Cakes

Ingredients:

• 1 and 1/2 cup whole milk (if you can’t steal some from a local bigwig, store-bought is fine)

• 4 tablespoons sugar, divided

• 1 packet of active dry yeast

• 2 large eggs, lightly beaten

• 1 and 1/4 stick unsalted butter (10 tablespoons), melted

• 4 cups all-purpose flour

• 1/2 teaspoon salt

• 1/3 cup warm water

• Lard (or vegetable oil)

Method:

1. In a large Dutch oven or stock pot, warm the lard or oil over medium heat. Use enough so that the liquid fat is at least three inches deep.

2. Heat the milk in a saucepan over medium-low heat, stirring constantly to prevent a skin from forming.

3. In a small bowl, mix the yeast with two tablespoons of sugar. When the milk is warm, pour it in the bowl, and cover tightly with plastic wrap for five minutes.

4. While the yeast does its thing, add the flour, salt, and remaining two tablespoons of sugar to a large bowl. Mix. This is also a good time to melt the butter and beat the eggs.

5. Add the butter, eggs, and water to the flour bowl. Once the yeast mixture is ready — it should be frothy — add to the dough. You should have a light batter, solid but springy.

6. Now that you can devote your attention to the oil, increase the heat until it gets between 355° and 370°.

7. Scoop the batter into spheres, bigger than a golf ball but smaller than a tennis ball. Gingerly add them to the oil one at a time. Be aware that each dough-ball you add will lower the temperature of the oil. Three at a time seems like a good amount.

8. As the oily cakes fry, rotate them occasionally to ensure they’re evenly cooked on all sides. Remove them once they get to the color of a Burnt Sienna crayon.

9. Top each cake with cinnamon and a spattering of honey. Sell for a healthy profit, as a metaphor for America.