Ask people who grew up in the 1980s what the ’80s sounded like and you’ll get thousands of different answers that vary based on taste, background, age, or even the mood a person happens to be in that day. But ask them to imagine what the happiest, most cloud-free day sounded like in that decade, maybe while driving to the beach with all the windows down, and I’m betting a whole lot of them would say: the Go-Go’s.

The Go-Go’s were the party girls, the women who made irresistible, SoCal-bright pop songs that pulsed with feminine energy. The documentary that shares their name, The Go-Go’s, which airs Friday night on Showtime following its debut earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival, doesn’t deny the accuracy of that reputation. These ladies partied; they had fun topping the charts. But this engaging, sturdily guided film from director Alison Ellwood (American Jihad, Laurel Canyon) argues forcefully that there is more depth and value to a group that fought and celebrated, broke up and reconciled, burned out and rocked hard for four decades. Their breakthrough single may have been called “Our Lips Are Sealed,” but what’s remarkable about the Go-Go’s is that they were a band of women charting their own path while refusing to keep their mouths shut.

Other women obviously became pop stars long before the Go-Go’s broke out with their first album, Beauty and the Beat, in 1981. But the Go-Go’s did it without a male manager or shot-caller and they did it as a self-made band in the mainstream, a realm then reserved pretty much entirely for men. Beauty and the Beat made them the first all-female group who wrote their own songs and played their own instruments to reach No. 1 on the Billboard album chart, a feat that, according to the film, no other band has matched. Ellison’s documentary retraces what happened to get the five core members — rhythm guitarist Jane Wiedlin, lead singer Belinda Carlisle, guitarist Charlotte Caffey, bassist Kathy Valentine, and drummer Gina Schock — to that point, and what happened after. But more important, it’s a story about female ambition, a quality that, more than three decades after the Go-Go’s first dominated MTV, is often still seen as a liability rather than an asset.

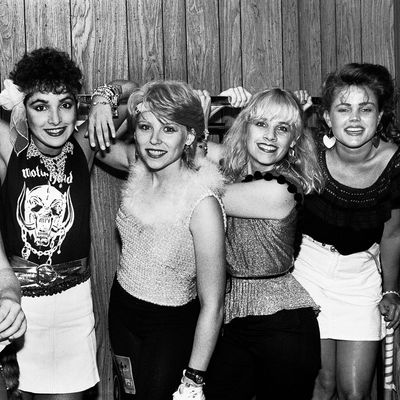

The Go-Go’s were born out of L.A.’s late-1970s punk scene, which is featured in some archival footage of the band at their earliest and most raw, in the days when Carlisle’s idea of fashion was black stockings paired with a trash bag. That gave them the freedom to be themselves and start their own musical adventure, even though, at that point, none of them knew how to play an instrument.

“In the punk scene it was like: great,” says Wiedlin. “You don’t know what you’re doing? Fucking do it.”

It was an all-female enterprise right from the start. The initial members were Carlisle, Wiedlin, Caffey, Margot Olavarria, and Elissa Bello. Their first manager, Ginger Canzoneri, signed up for the job simply because she was heartened to see them practicing together. “I love communities of women,” she explains. It was Canzoneri who, despite her inexperience as a manager, also was smart enough to make sure the band didn’t sign away their publishing rights when they made their first record deal.

That record deal came after the band replaced Bello on drums with Schock, embarked on a tour of England with the Specials, where they were met with plenty of misogyny from male-dominated audiences (“Show us your tits,” one jerk yells during a gig), and after getting rejected by major labels whose executives didn’t think a gaggle of women could sell records. “Best of luck with your enterprising all-girl band!” reads a line in one of the letters.

But the most seismic moment for the Go-Go’s, pre-fame, came when Olavarria, who originally came up with the idea for the band with Wiedlin, was ousted from the group. Olavarria considered herself a member of a punk band, in name and in ethos, but her colleagues were trying to break through and become bigger. “It was just becoming less about art and more about money,” Olavarria says. After falling ill and missing a New Year’s Eve gig, she was replaced by Valentine, a guitarist who said she could play bass, then taught herself how over a few days while on a coke binge.

After that falling out, there was backlash against the Go-Go’s within the L.A. punk scene that launched them. “We had sold out,” Carlisle says, describing the gossip about them. “We weren’t a punk band. We were” — here comes that word again — “ambitious.”

Their ambition got them a No. 1 album — fun fact: the band had so little money that Canzoneri had to buy the white towels the band members wear on the cover of Beauty and the Beat from Macy’s, then return them; more hit records and singles (“We Got the Beat,” “Vacation,” “Head Over Heels,” etc.); and a significant spot in the rotation on the then-brand-new MTV.

But it also led to a lot of drinking and drug use, particularly by Caffey, who was a heroin addict, and the dumping of Canzoneri in favor of more experienced management, a decision they all seem to regret. (“We should have just stuck with Ginger,” says Wiedlin.)

The Go-Go’s were viewed as a celebration of sisterhood and created in that spirit. If you watched the music videos of them frolicking in Beverly Hills fountains and fake waterskiing, all you saw was their effervescence and their playfulness. Behind the scenes, things got ugly. Eventually arguments about how much everyone was being paid — Caffey and Wiedlin, as the primary songwriters, were making the most money — led to the dissolution of the band by the mid-’80s. Their determination and the chemistry were, in part, what made them so great. But when those factors got out of balance, they also contributed to their undoing as a unit.

The band members speak candidly about their conflicts and their exploits. At one point, while recounting the day the band broke up, both Valentine and Schock imply they feel ill all over again. Ellison is deftly able to convey the hurt that they felt, while capturing the joy that radiates, still, from their music and performances.

As even casual Go-Go’s fans know, over the years they eventually managed to reconcile, get back together, put out a new album in 2001 called God Bless the Go-Go’s and continue to tour. So in a way The Go-Go’s really is a testament to sisterhood and how age, wisdom, and an understanding of how rare and special certain relationships are can bust through even the most hardest grudges.

The Go-Go’s is also a strong argument for why this band should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame already. In the closing moments of this documentary, several sources — journalist Chris Connelly, Stewart Copeland of the Police, and riot-grrrl pioneer Kathleen Hanna — note how ludicrous it is that the women who have the beat haven’t already been inducted. “Well, they’re in my Rock and Roll of Fame,” Hanna says. They also deserve to be in the one in Cleveland, and if you’re not sure if you agree, just watch this documentary. If you still don’t agree after that, do me a favor: Keep your lips sealed.