Herbie, the sentient VW first introduced in 1968ÔÇÖs The Love Bug, is in love. In his third movie, 1977ÔÇÖs Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo, heÔÇÖs fallen for a sleek (and, weÔÇÖre repeatedly reassured, female) Lancia racer, having made his intentions known with some loud, hyperactive sounds of vehicular horniness. But while his kindly chief driver, played by actor Dean Jones, supports this automotive union, his irritable partner, played by Don Knotts, does not. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt mind having a car that has a heart,ÔÇØ Knotts steams to Jones, ÔÇ£but I will not tolerate a car falling in love with another car!ÔÇØ

This curious transgression is one of many moments buried among the Disney+ archives. A few weeks before its launch in early November of last year, the streamerÔÇÖs Twitter account began an epic, baffling thread, in which the company listed every single movie that would fill the platformÔÇÖs coffers, one by one, in chronological order. We expected the Marvel films, Star Wars, and the super companyÔÇÖs many animated classics. But peppered in between the stalwarts were countless Disney Vault oddities: implausible animal farces, strange Christmas movies, far more Herbie sequels than we remembered, and something called Fuzzbucket.

Almost half a year later, IÔÇÖm still miffed by these titles. The only thing that has changed is that, well, a global pandemic has hit, and I, like many of you, finally have time to wade through Disney+ and answer for myself: Who is Sammy, the Way-Out Seal?

Dubbing the lesser-known Disney Vault offerings oddities is perhaps unfair. A number of these family-friendly comedies were hits at the time of their release, with some grossing even more than the companyÔÇÖs well-known animated classics. (The Love Bug, for example, was the third highest-grossing film of 1968, after 2001: A Space Odyssey and Funny Girl, earning over $51.2 million at the domestic box office.) In the ÔÇÖ60s alone, Disney released only three animated features versus 47 live-action movies (plus one hybrid, Mary Poppins), because where the toons took time and money, the live-actions were largely cheap to make. As a kid, I watched a few, in school, at summer camp, at home. I saw The Ugly Dachshund no less than three times, and distinctly remember The Shaggy D.A. and The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes.┬á

These films were of a particular strain of live-action Disney: comedies made during the ÔÇÖ60s and ÔÇÖ70s, during the era of civil rights, counterculture and sexual revolution, the Vietnam War, Watergate, and the death of Walt Disney himself. But youÔÇÖd never have any sense of such tumult watching them. Comedies like The Ugly Dachshund ÔÇö about a Great Dane who thinks heÔÇÖs a wiener dog ÔÇö contain no social commentary or parallels to real life. If they do acknowledge the outside world, itÔÇÖs with kid gloves. The Shaggy D.A. ÔÇö released two and a half years after Nixon resigned ÔÇö begins with a song featuring the lyric, ÔÇ£Let the past be water under the gate,ÔÇØ but makes no mention of the federal political scandal thereafter. If you squint, you can almost see hints of the WomenÔÇÖs Liberation Movement seeping into certain stories; the female leads are rarely stay-at-home moms but independent, employed, and quick to battle immature male leads, even if they always fall into their arms by filmÔÇÖs end.

One actor who played more than a few immature male leads was Dean Jones. When his acting tenure began at Disney, live-action comedies were still a relatively new addition to the companyÔÇÖs vast repertoire. It took till 1959 ÔÇö┬áthree decades into the companyÔÇÖs life, and almost a decade since its first entirely non-animated feature, 1951ÔÇÖs Treasure Island ÔÇö┬áfor Disney to make the lowbrow charmer The Shaggy Dog, about a bookish teen (Tommy Kirk) who involuntarily transforms into the one thing his retired mailman father (Fred MacMurray) hates:┬áa canine. Audiences loved it; it was the most profitable Disney movie of the time. And so did Walt, who described the next comedy, 1961ÔÇÖs The Absent-Minded Professor, as ÔÇ£one of the funniest comedies that ever came out of this town.ÔÇØ

Walt was less hands-on with the live-action movies than he was with the animated features (by the late ÔÇÖ50s he was barely involved with those either, tending instead to his next-level amusement-park spectacular). But Walt handpicked Jones for a role in That Darn Cat! after catching sight of him on the short-lived military comedy Ensign OÔÇÖToole, which came on right before Walt DisneyÔÇÖs Wonderful World of Color. Up until that point, Jones had played everything from drug addicts to soldiers onscreen, not to mention the DJ who gave Elvis his first radio play in Jailhouse Rock. But he didnÔÇÖt have a brand until Walt rang. That brand ÔÇö wholesome, slapstick ÔÇö has so stuck with him that itÔÇÖs hard to believe the guy from BlackbeardÔÇÖs Ghost originated the role of Robert in Stephen SondheimÔÇÖs game-changing Company. (You can hear Jones slay the barn burner ÔÇ£Being AliveÔÇØ on the original cast album.)

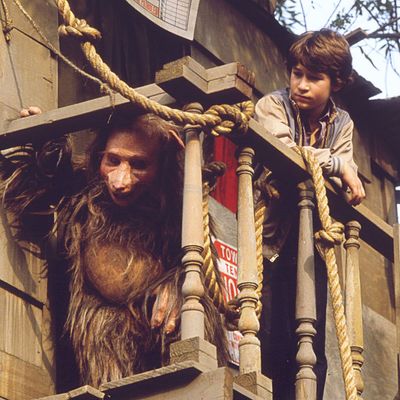

Indeed, Jones, who died in 2015, never had a more consistent run of roles thanks to Disney, who kept him employed at the company for 12 straight years and nine films. His movies tended to check the same boxes: a wacky gimmick punctuated by cut-rate effects and impressively inoffensive humor, often ending in a climactic car chase. Animals were optional but highly recommended. They had braying opening title theme songs and copious rear projection, and kept a stable of aging, mugging character actors ÔÇö┬áEd Wynn, his son Keenan Wynn, McHaleÔÇÖs Navy antagonist Joe Flynn, even Elsa Lanchester ÔÇö┬áflush with paychecks.

Walt always said he never made films for children; he wanted everyone to imbibe Disney, young and old. So as stridently as Dean JonesÔÇÖs comedies avoided realism, they still prominently featured adult matters few children would understand: Million Dollar Duck ÔÇö┬áone of three movies Gene Siskel ever walked out on ÔÇö┬áis about a fowl laying golden eggs, which wind up disrupting the global economy. Snowball Express depicts the grunt work of launching a skiing resort in an uncertain tourism market. In Monkeys, Go Home! (not on Disney+, alas), Jones inherits an olive grove in rural France, but when he trains chimps to pick his product for free, he angers locals, who accuse him (rightly!) of eliminating potential jobs. In the end, though, these movies offered a simpler version of adult life ÔÇö┬áperhaps one that Walt wished could be, filled with wacky animals and Flubber and pirate ghosts and thirsty cars. Here, he could give viewers a taste of what eternal arrested development looks like, where the culture surrounding our infantile adult protagonists is fantastically uncomplicated. ┬á

Forgettable and square as they are, the Dean Jones comedies set a precedent for the companyÔÇÖs future: They revealed that there was a market for movies that pointedly separated themselves from the pressures of the real world. Present-day Disney franchises are only slightly more hip to a changing culture than the Dean Jones comedies; Star Wars and Marvel films donÔÇÖt even flirt with an R-rating, and if they embrace progressive ideals (LGBTQ+ representation, for example), they do so superficially. Nonetheless, in the half century since JonesÔÇÖs heyday, Disney has ballooned into a corporate Galactus. Perhaps Walter Elias Disney sought to transform the culture, but when that failed, his successors simply bought it.