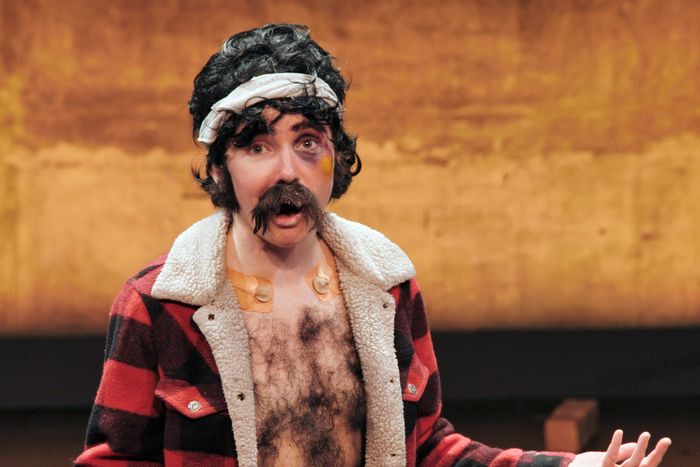

A short man roars onstage on a toy-size motorcycle, his black-and-red-checked lumberjack coat swinging open over his bare chest. He spoons up a mouthful of protein powder, spits it out past his enormous Yorkshire-terrier mustache, and lights the resulting dust cloud on fire. Grrrargh! He raises an ax high over his head, but it boinks delicately off a log. After all, inside this guy Nate — a bellowing, grimacing Napoleonic bro — is a very little lady.

When I speak to his creator, Natalie Palamides, in her Los Angeles home, she is whatever the polar opposite of Nate is, comfy in a purple maxi dress and yellow-lensed glasses. In normal life, Palamides doesn’t do the chaos-Muppet faces that characterize her comedy, and her ferocious energy is groggy at ten in the morning. But at any hour, playing any gender, her voice is her superpower. Low or high, Palamides sounds like a distracted Powerpuff Girl (she’s actually the voice of Buttercup in the recent series reboot), with the exact mix of gravel and squeak that makes you think something tiny is about to kick your ass. For most of her weird and wonderful Netflix comedy special, Nate, Palamides is unrecognizable, growling provocations from under a huge black John Travolta wig. Her costume lampoons and exaggerates masculinity and occasionally lets a glimpse of femininity peep through: Black cotton chest hair drifts over bared breasts; a stretchy rubber penis — much abused — is tied into little briefs. As a production, Nate draws from discomfort comedy, clown-character traditions, even cartoons. Imagine Andy Kaufman meets Sacha Baron Cohen meets Elmer Fudd — if all those fellas were women with no hang-ups about their boobs.

The show isn’t merely drag mayhem. As Nate tells us about a recent heartbreak and the adult painting class he’s taking to work through his feelings (“C’mon, Nate! Express yourself!”), the macho little pepper pot asks — often literally — questions about agency and vulnerability. If the comedy weren’t so profane, Nate would feel like an after-school special posing a moral conundrum (what constitutes consent?). Swaggering around in oversize boots, Nate talks earnestly about permission, but he constantly demonstrates coercion. “All you gotta do is ask,” he insists as he tries to cop a feel from a woman in the front row. “Ask!” the audience chants obediently and on cue. The conventions of being an audience member at a comedy show, with the assumption that one be a “good sport,” form a wave front of pressure; Palamides manipulates that pressure to force theatergoers past their comfort zones. Can Nate get a guy to call a woman a “whore-ass”? Can a half-naked Nate — five-foot-one in shoes — persuade some other fellow to wrestle topless? Only every goddamn time.

Long before the shutdown, Nate had achieved international success: The show was a crossover smash at the Los Angeles Upright Citizens Brigade, toured twice to New York, and won the Total Theatre Award at the 2018 Edinburgh Festival Fringe. After seeing it in Los Angeles, Amy Poehler and her production company put their muscle behind it; Nate will come to Netflix ready to be this season’s Nanette-level conversation piece. This is not the typical journey for foulmouthed, outer-orbit Weird Clown stuff. Palamides is part of a small community of tight-knit clown creators who have been making work in L.A. for a decade, but the venues are miniature—a sold-out show might top out at 95 people. In the normal scheme of things, there’s an intermediate step between the Deep Fringe and the Netflix special, but Nate jumped that gap.

Palamides, now 30, has wanted to be a comedian since she was a little kid: Growing up outside Pittsburgh, she was already making home videos in her backyard. Students would stop her in the halls at school to do bits. Her lodestars were Disney (she’s still obsessed to the point of having a podcast called Hidden Mickeys) and Austin Powers. “Looking back, I’m like, Oh, maybe it’s like a little bit early for a 9-year-old to be quoting the movie,” she says. “It was, ‘Oh yeah, baby. I’m horny.’ And my dad would be like, ‘Yeah, don’t say that.’ ” But it was too late: She had worked out that being small and talkin’ smut could get laughs.

Her college experience, at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, couldn’t have been more wholesome. (When you cross a road in the town, the voice of the walk signal is an impression of Jimmy Stewart.) But Palamides’s theater professor Rick Kemp introduced her to the study of European clown, which goes beyond mere entertainment, turning foolery into a quasi-spiritual pursuit. After honing her mask and commedia skills, Palamides was plucked out of the undergrad scene by Philadelphia’s beloved Pig Iron Theatre to work on “devised” theater — a collaborative form in which an ensemble improvises from a prompt — and she learned to make a play without a script. Another performer with the same interests might have gone on to study la tradition with grand French masters like Philippe Gaulier (Baron Cohen was once a student), but Palamides was impatient to get started on her senior-year-in-college goal: climbing the Los Angeles comedy ladder to get to Saturday Night Live.

In L.A., she hit those SNL-approved rungs fast, almost immediately joining a team at the Upright Citizens Brigade and booking voice-over and commercial work. She missed the am-I-falling-or-flying freedom of true absurdity, though. Luckily, L.A. had become a global center for clown performance, revolving around three important organizations: the Clown School, where instructors teach the sweet-natured “red nose” style; John Gilkey’s the Idiot Workshop, where the form is stripped to its core of being grotesque and goofy in public; and the Lyric Hyperion, run by the community linchpin Dr. Brown, a.k.a. Philip Burgers, a Gaulier-trained clown with a deep footprint in cringey, awkward-hilarious character work. Clown is a liberating corrective to the competitive nature of entertainment in L.A., says Palamides’s friend and co-clown Chad Damiani, where everything is built around getting discovered. Nobody looks cool while clowning: The failure is the point, the face-plant the reward. “We’re just the most foolish versions of ourselves,” he says.

Palamides started taking classes at the Idiot Workshop and the Lyric, and Damiani remembers the first time he saw her performing in the former group’s ensemble Wet the Hippo. “It was five very intense guys onstage at a little independent improv show, and she was just more fierce than any of them. She was so fearless and gross and funny.” In Palamides’s best work, a character always points out the sheer squelchy oddness of having a body that desires or is desired; 20 years after The Spy Who Shagged Me, her comedy signature was still that Austin Powers–esque repulsion-seduction. In one 2013 Wet the Hippo video called “Salad,” she fantasizes filthily about eating a salad out of a guy’s pants; in a sketch at UCB, she’s a promiscuous anthropomorphic egg who complains to the manager at L.A. sandwich sensation Eggslut. Throughout “Start Objectifying Women,” a viral video shot by Seth Allison, her character insists, in nastier and nastier ways, on being made into an object—first a man’s broom, then his ice machine, then his garbage disposal.

At the Lyric, Palamides decided to develop longer, more theatrical pieces. She began relentlessly workshopping bit after bit at variety shows, open-mic nights, and clown classes. She’d put on a strange outfit and go out in front of an audience with almost nothing planned, hoping to create one moment onto which she could build something new. Eventually, with Dr. Brown acting as director and mentor, she repurposed the Eggslut costume for her first full-length, hourlong show, Laid, about a woman who gives birth to an egg every day and has to decide whether to raise it or eat it (mess ensues). Laid went to the Edinburgh Fringe, where it was a wild success, winning Palamides the 2017 Best Newcomer Award. It also paved the way for Nate.

That September at the Lyric, during a boot-camp clown incubator, Dr. Brown asked participants to develop a bit in which they felt at risk. Palamides had long been curious about wrestling an audience member. How much danger would she be in? What could she get away with? (Kaufman’s experimental comedy around “inter-gender wrestling” may have been murmuring in her memory.) Nate was a character she’d dreamed up for a Pig Iron workshop years before — “this douchey guy chugging a two-liter bottle of soda watching TV and burping” — so she dusted off his mustache to see whether melancholy masculinity would be a good thing to take to the mat. In her incubator show, she tried it with Nate topless. At first, the entirety of the gag was the asymmetrical match. “Part of me thought it was funny to push the boundaries with what a woman’s body is like,” she says, “because men wrestle shirtless all the time and it’s not taboo at all! But to wrestle a topless woman has this taboo quality about it, and I thought, Isn’t that interesting?” After the incubator, she started to iteratively shape a love story for the chest-thumping pip-squeak. It was only then that she allowed Nate to start asking questions about consent.

Palamides is not willing to call what she does true clowning. “You’re taught that there’s only one pure clown that comes about every generation,” she says. These are the Charlie Chaplins, the Lucille Balls, the divine idiots. “It’s very rare. Anybody can learn to incorporate clown techniques, but to be a clown is something that’s not as easily obtainable,” Palamides continues. “There is an innocence to clown. There’s not supposed to be any sort of sexuality or anger.” And in Nate, there is certainly sexuality and anger, alongside a deep stripe of masochism. Palamides’s deepest pleasure comes from making the audience uneasy. She thinks, Well, if they’re there, they’re gonna play with me. She can use any response — a yes or a no or even silence — to lead to further humiliation. Laughter sours in your mouth. The questioning becomes a means of control. “It was like a puzzle,” she says. “It’s fun to think about how I could still get whatever I wanted, no matter what the audience said.”

This is where the live-wire danger in Nate comes from, the feeling that you’re discussing agency with someone who’s playing a dominance game herself. Whether watching Palamides in person or onscreen, one feels the tingle of vicarious terror as participants’ eyes grow more and more frightened. But Nate’s eyes change too. In one crucial moment, the mustache slips aside and we see what seems to be the “real” Natalie. Is it Nate up there, naked and strong? Or is that Natalie, naked and vulnerable? In the most finely calibrated manipulation of the evening, Palamides turns the waves of audience attention and has them crash down most punishingly on herself. The show ushered us there, coaxed and bullied us. Despite her protestations, this radically undefended moment is absolutely the core of clowning — the revelation of the human in the performance, the glimpse of the true fool, the unadorned and unpretending self.

*This article appears in the August 31, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From Fall Preview

- Which Movie Studios Won and Lost the Summer of No Blockbusters?

- Everything to Know About the Looming PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X Showdown

- The Hardest Elena Ferrante Lines I’ve Translated

- Let Amber Ruffin Be Your Guide

- Explore the World of Artists in Quarantine