On the still slightly wild Upper West Side where I was raised in the early 1970s, I saw plenty of cops, but only in my peripheral vision. The police officers who felt real to me were, paradoxically, the ones I watched on TV. The West 70s, at that time, were starting to gentrify, with drab new brick-faced high-rises next to long blocks of low-slung tenements, and the populace was a semi-integrated blend of Black, Puerto Rican, and Jewish longtime residents; gay men staking their claim to a new enclave three miles north of Greenwich Village; and the start of a wave of upwardly striving singles, couples, and families ÔÇö yuppies before there was that word to describe them ÔÇö who were attracted to the bookshops, bodegas, delis, and Chinese restaurants that lined the side streets.

My resolutely anti-suburban parents somehow fit in. Our part of the Upper West Side was neither the most luxurious nor by any means the roughest neighborhood in Manhattan in which to raise kids. My Jewish father, an entertainment lawyer, and my Catholic mother, a doctor at St. VincentÔÇÖs Hospital downtown, always took defensive pains to assert to my younger brother and me that we were ÔÇ£comfortableÔÇØ (which meant we had a nice rented apartment in a housing complex and a station wagon) but certainly not rich like the people on Central Park West, let alone those on the other side of the park.

New York was still the down-at-the-heels city of bankruptcy, blight, and seediness that ranged from the amiable to the menacing, so there were also, ambling up and down Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue, a fair number of heroin addicts, prostitutes, and pimps who actually dressed like they did on TV shows and movies set at that time, in fake furs, neon hot pants, and spectacular platform shoes. As a small boy, I took in stride much of what I saw and heard. On the sidewalk, my mother would briskly move me and my brother past the junkies and sex workers and tell us not to stare. In the afternoons and early evenings, they would congregate on or around the small pedestrian islands just north and south of the 72nd Street subway station, officially called Sherman Square and Verdi Square but known to all residents (and immortalized in a 1971 Al Pacino movie) as ÔÇ£Needle Park.ÔÇØ At night, the addicts and streetwalkers would hang out at the large diner across the avenue, guzzling endless paper cupfuls of Orange Julius, a chokingly sweet soft drink akin to a melted Creamsicle. ÔÇ£All junkies want sugar. TheyÔÇÖre like fruit flies,ÔÇØ my father said in the firm tone he used to deliver notable information as he hustled us along. And: ÔÇ£Never touch anything that looks like that,ÔÇØ as he pointed at the syringes and bits of charred-looking tinfoil that lay along the curb.

It sounds chaotic, but it felt routine. The raw material for scores of cop shows and movies seemed duller and more ordinary in real life; even the constant shrilling of sirens was a kind of ambient background noise, not even worth a glance toward the street. Occasionally I would see patrolmen blandly ushering somebody off a corner and into a squad car as red lights raked the building walls. Neither they nor the people they were arresting seemed especially upset, just bored and irritated, which is how all adults look to those who are not yet bored and irritated. Those officers were, as almost everything in a kidÔÇÖs world is, an unquestioned fact of life, but at the time, they had no deeper meaning to me than did the friendly brown dog dressed in blue and riding a police motorbike on the cover of Richard ScarryÔÇÖs What Do People Do All Day? They were people in uniforms, arresting other people who wore different uniforms. And, I knew, they were the men you were supposed to call if something was wrong, as it often was back then, when muggings and robberies happened to everyone and the NYPD wasnÔÇÖt expected to solve those crimes as much as to tally them.

And then, at night, the TV would go on and I would be transfixed by the cops I saw there, the men who seized a piece of my consciousness when it was at its most impressionable, captured my imagination, and made me believe in their effectiveness. I had not thought about those Hollywood policemen for a very long time. But this spring and summer, they came back to me ÔÇö more accurately, I realized that they had never left. The seemingly countless videos of men in uniforms committing acts of casual brutality that have filled our screens have forced us to understand something that is not at all new but, thanks to smartphones, is now visible and undeniable. For many white Americans, especially those of my generation, it has been a year of belated education, anger, and no small amount of shame. I have become painfully aware of how little, over the decades, I have had to think about cops, largely because cops donÔÇÖt spend all that much time concerning themselves with me. People who look like I look fall squarely in the category of those the police ÔÇ£protect and serve,ÔÇØ not those they target.

But although the term ÔÇ£white privilegeÔÇØ covers many of the things I didnÔÇÖt have to grow up fearing about the police, it doesnÔÇÖt quite encompass the strangeness of what I did grow up thinking and feeling about cops, something I rediscovered only when I started to rewatch the police shows of my childhood. They were, if not exactly nuanced, less baldly retrograde than I had imagined they might be ÔÇö but they were also undeniably indoctrinations into what authority meant and where you fit into it, and as such, their mildness only made them more effective. They were, for me, seductive in ways I had not wanted to think about for decades. Those imaginary men in blue had an unnerving and enduring hold on me. They were my gateway ÔÇö to the world of adult TV, to the mysteries of adult men, to my own father, and, as it turned out, to the lonely realm of my own unnameable longing.

I learned all about the police ÔÇö or thought I did ÔÇö when I was much too young to be aware that I was learning anything. Like many proto-gay kids of my era, I would have been happy to take in nothing but cartoons and sitcoms ÔÇö Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, The Brady Bunch ÔÇö forever. But my father would mutter ÔÇ£Why are you watching that garbage?ÔÇØ whenever he walked by the TV set, and the contempt that seemed to splash onto both the programs and me left me feeling what I already knew on some level ÔÇö that I was failing a kind of test. I knew he would have preferred that I watch the shows that he and my brother enjoyed: Westerns like Gunsmoke and Bonanza. But stories of men on horses threatening each other or fighting over cows or fences or land bewildered me. I was an allergy-ridden boy who needed to be injected with epinephrine and sent to lie down every time I got near a pony, and so the main subject of those dramas always felt to me like it was the mysterious absence of asthma. Only Michael Landon ÔÇö the sensitive son on Bonanza (there was no one sensitive on Gunsmoke) ÔÇö was enough to keep my attention from wandering for an hour, even if I didnÔÇÖt quite understand what his character Little Joe was doing or why I was so interested in watching him.

I needed a better connection to my father than I had, and the one I found was Adam-12, a series that was, in a way, designed with almost insidious perfection as My First Police Show ÔÇö a smooth transition from kidsÔÇÖ TV into the grown-up world. For one thing, it was only 30 minutes; for another, that half-hour was usually divided among two or three bite-size, easy-to-follow, often amazingly uneventful stories of two white cops on the beat in Los Angeles (a city as exotic as Mars to a child who had never been west of New Jersey). For most of its seven-year run, it aired at 8 p.m., accommodating my bedtime. It was even, literally, the perfect shape for a TV series, by which I mean a show to be viewed on an old-fashioned 4:3 screen. The visual that dominated almost every episode was a two-shot of its main characters: Officer Pete Malloy (Martin Milner) ÔÇö about 30, cranky, and sour ÔÇö behind the wheel and, next to him, Officer Jim Reed (Kent McCord) ÔÇö younger, gentler, more idealistic, a comic-book-handsome family man. I had a crush on Jim Reed years before I knew what a crush was or what it meant. I ached to have something from him ÔÇö to be driven around on patrol, to be taught a useful skill, to be told I was okay by him, to be his Robin. I could not have found words for any of that. Like Small Alison in Fun Home singing about her first stirring of desire in ÔÇ£Ring of Keys,ÔÇØ the sentence that began, ÔÇ£I

want  did not have an ending, just an ellipsis.

Adam-12 premiered on NBC in 1968 in the wake of protests and riots in Newark, Detroit, and Watts. When I revisited the series for this story, I expected to find a racist relic, as so much of pop culture from half a century ago turns out to be. What I found ÔÇö and I have binged an implausible amount of Adam-12 in the last several weeks ÔÇö was more complicated: an anxious, self-conscious combination of well-intentioned semi-liberalism about race that was counterbalanced by angry generational conservatism. From the beginning of its first season, the series featured Black policemen, but in the background rather than as main characters. One of them, an amiable, clean-cut rookie like Jim Reed, recurred several times, and there was even a special fact-based two-part episode about the first Black woman to become an L.A. police commissioner, a nice lady played by Imitation of LifeÔÇÖs Juanita Moore who asked to go on a ride-along so that Malloy and Reed could teach her about policing. Black people were frequently among those the cops would help out ÔÇö a nurse who couldnÔÇÖt afford Christmas presents for her son, a couple whose toddler daughter Malloy saved after she choked when they turned their backs for a minute. To them, the cops were heroes, a point that was underscored every year by a different special holiday episode about community service.

It was implicit in those stories that Black people had to struggle just to get by, but the show didnÔÇÖt care to explore the reasons; it was just how things were, and the point was that at least they were there and had the same jobs as, you know, regular people. That was pretty much the extent of what I was then being taught in early elementary school about equality ÔÇö that it was good and that America had it now. As I watched, sitting on the floor with my father behind me in his swiveling armchair, I could feel his eyes resting on me. I hoped it was with approval; I sensed that there was consequential information about the order of things that I was supposed to be absorbing.

Adam-12 was set in the flat, arid Los Angeles of single-story businesses and warehouses situated along wide, sunbaked avenues, and it was mostly about workaday problems, not urban unrest. The cops were depicted as social mediators who spent a lot of time on domestic disputes (almost always sparked by a comically overwrought or angry woman) and as patient explainers of the importance of the law to traffic violators. The more serious miscreants were burglars, car thieves, drug users, and anyone who remotely qualified as a ÔÇ£hippieÔÇØ; arrogant, shaggy-haired white kids in beads, sandals, and mock dashikis were all treated as potential members of the Manson Family. I learned quickly that they were bad news; you could tell by the way they looked and the way they mouthed off to Reed and Malloy. The Black citizens on the show rarely did that; they were what many white viewers of the time would have unhesitatingly referred to as ÔÇ£the good ones.ÔÇØ This was what I first came to grasp as the profession of policing: white cops living in the center of the screen and therefore of the world, there to watch over everyone, Black and white, and shield them from troublemakers. It felt like knowledge worth holding onto.

I think my father may have been one of the men who used the phrase ÔÇ£the good onesÔÇØ about Black people. I donÔÇÖt know where else I would have heard it, but I canÔÇÖt be sure; he died 40 years ago, when I was 14 and just beginning to be old enough to challenge his attitudes about race (we never got around to homosexuality). A full, fair picture of those attitudes is, after so much time, beyond my ability to excavate; it resides in answers to questions I can only ask of a ghost, and how much of him still lives inside of me is something I will never fully know. One of my first memories of him saying anything on the subject came when my allegiance shifted from Adam-12 to The Mod Squad, the ÔÇ£countercultureÔÇØ police procedural that also premiered in 1968, but on ABC.

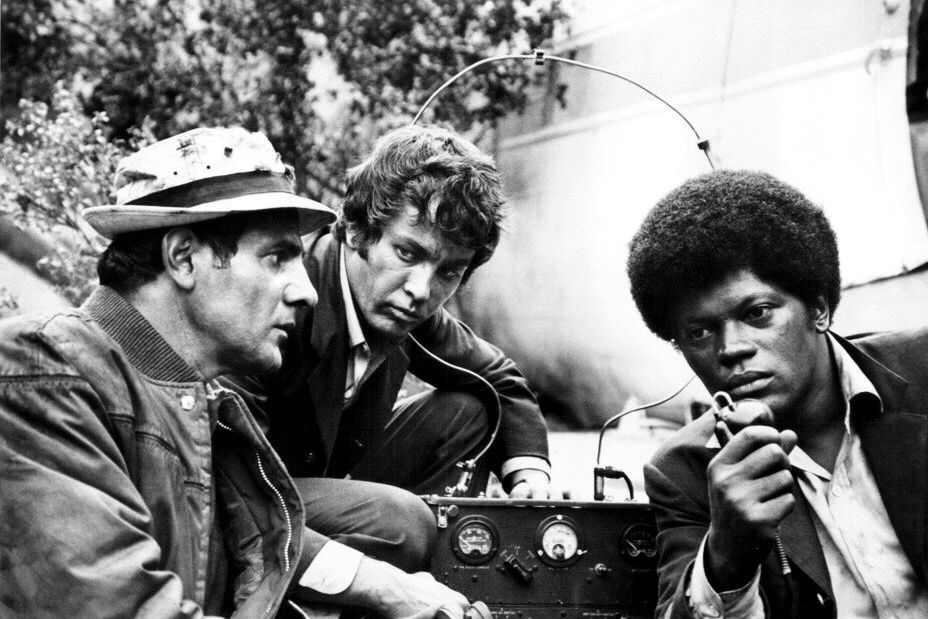

The Mod Squad is about three formerly reckless youths, bad kids plucked from the streets and turned into undercover cops because they could blend in easily with flower children and campus protesters and radicals and runaways. Pete, played by Michael Cole, was the rich white Beverly Hills rebel with a Warren Beatty mane, green-tinted shades, provocative chest hair, and a wounded James Dean mumble. (Why did I think he was so interesting? Never mind, I remember.) Julie (Peggy Lipton, later of Twin Peaks) was the beautiful girl whose mother was a prostitute and who was arrested for ÔÇ£vagrancyÔÇØ (I had no idea what that was and was disappointed when I later found out it was nothing particularly shocking).

And then there was Lincoln Hayes, who had grown up in Watts as one of 13 children. Anyone of a certain age who watched The Mod Squad will remember how transfixing Clarence Williams III was as Linc. He had an Afro, sunglasses, turtlenecks, and medallions, not to mention huge reserves of sangfroid; he also possessed one of the great thousand-yard stares in all of television, so that when he got his assignment from the captain, some weeks you couldnÔÇÖt tell if he wanted to wrap his fingers around his throat or was just quietly considering all possibilities. LincÔÇÖs trademarks ÔÇö an oft-repeated clip of him icily shrilling ÔÇ£Liiiiiiiin-coln!ÔÇØ when asked his name, or the word ÔÇ£Solid,ÔÇØ uttered with a righteous raised fist, were pretty good pop-culture currency for a third-grader to have in his pocket. The first time my father saw me raise my fist, he barked, ÔÇ£DonÔÇÖt do that! YouÔÇÖre not some Black Panther!ÔÇØ I would like to be able to tell you that he was giving me a lesson in the problematics of cultural appropriation, but it was 1972. What he was saying was, DonÔÇÖt let me catch you behaving like a Black kid.

Which is complicated because he never would have said it. My father ran his own very small law firm. Most of the people he represented were in show business, and most of them were Black. With his female clients ÔÇö the lead singer of a girl group, a stage actress, an early disco star ÔÇö he was deferential, generous, courteous, paternal. He would help to pry them free from abusive marriages or penurious contracts or unscrupulous white managers (ÔÇ£Motherfuckers,ÔÇØ he would mutter, lighting his pipe). Sometimes he would bring them home for dinner or take us out with their kids on the weekend for ice-skating. He was less patient with the men, who were not ÔÇ£the good onesÔÇØ: They did drugs, stole cars, pulled guns, got arrested. I learned almost the entirety of my profane vocabulary from listening to him curse people out on the phone, pacing the kitchen floor as dinner got cold, yelling his way to his first heart attack. I learned other words as well. ÔÇ£If I ever hear you say the N-word, IÔÇÖll slap you across the mouth,ÔÇØ he said to me after he realized I had been listening to one of those calls. (He didnÔÇÖt use the phrase ÔÇ£the N-word.ÔÇØ)

ÔÇ£You said it,ÔÇØ I said.

ÔÇ£I say it because that way, the people I work with know that I speak their language,ÔÇØ he said. I couldnÔÇÖt decode that, but I remember thinking that the perfect comeback would be a fist up and a ÔÇ£Solid!ÔÇØ I also remember knowing that it wouldnÔÇÖt feel worth the slap.

In an era when all TV shows have age-suitability ratings and content guides, the vigor with which adult cop shows of the 1970s were marketed to children seems shocking. But in fact, immense energy was invested in embedding those series in the collective consciousness of children. Dell published 15-cent Mod Squad comic books, and Topps sold Mod Squad chewing gum. You could get a wheel of Hawaii Five-0 Viewmaster slides and click through color pictures of unsmiling, black-suited Steve McGarrett arresting HonoluluÔÇÖs miscreants, or buy Milton Bradley board games based on Columbo, Starsky & Hutch, or Kojak (ÔÇ£Be a part of thrilling police action on the city streetsÔÇØ), which allowed young players to use informants to track down a suspect hiding in a building. I coveted the Adam-12 lunchbox, which had an illustration of Malloy and Reed helping a little boy on one side and on the other the two of them crouching with their pistols drawn, ready to fire on an unseen suspect. The images were two halves of the same coin.

Many of those shows donÔÇÖt stream today; in order to revisit The Mod Squad, I had to purchase a 39-DVD set that is only slightly smaller than the beat-up woodie wagon in which Julie, Linc, and Pete used to ride around together, Scooby Doo style. (Related: Is anyone interested in buying a slightly used 39-DVD set of The Mod Squad?) I prepared to watch with dread, realizing that the series I had loved so much as a kid was actually a five-year enshrinement of the narc as hero.

But the show, though it was goofy, cartoonish, and apolitical to the point of deliberate indifference at least half the time, is also a fascinating document of how pop culture sought to resolve some of the most unresolvable issues in our society during its run from 1968 through 1973, when the country felt to people of my parentsÔÇÖ generation like it was flying to pieces. In many of the episodes, the squad members function not as narcs but as translators, rendering the youth community (of rebels, of hippies, of revolutionaries) comprehensible to their boss ÔÇö and vice versa ÔÇö and solving a problem before it comes to a head. Their targets included racists, pushers, even a right-wing arms dealer.

Still, the title of the show might as well have been The Good Ones, both in reference to the three heroes themselves and to the process of social sorting that gave many of the hours their plot lines. It was occasionally the squadÔÇÖs job to root out the bad elements who were undermining a good cause. (Good causes included helping Native Americans, mentoring kids in the inner city, trying to make slums more livable, and basically any protest that was not against the police and wasnÔÇÖt violent.) And the people they helped were almost always grateful ÔÇö a trope meant to reassure the white audience at whom virtually all TV programming was then aimed. ÔÇ£Oh, my!ÔÇØ said a blind young Black woman named Janny (Gloria Foster, later The MatrixÔÇÖs Oracle) as she reached out to caress JulieÔÇÖs long, straight blonde hair. ÔÇ£You must look like a princess!ÔÇØ

Later in that hour, a complicated and sad romantic tension is established between Janny and Linc  the private glimpse of the connection between two Black characters its audience was granted was, at that time, rare on any TV show. The Mod Squad was largely goodhearted, but in a way that made clear that the parameters of what constitutes a good heart were defined entirely by its white writers and producers. If the show were on now, it would be in sympathy with the Black Lives Matter protests, but it would single out those who lit fires and threw bricks as people who dont truly believe that Black lives matter, and it would definitely not endorse defunding the police, because without the police, who would be able to explain all of this to the young people? Cops knew everything, could solve everything, could protect everyone  if you would just let them do their work.

By the time I was 10 or 11, I had learned to bury my crushes on men so deep that they would be undetectable by anyone, even, if I was vigilant, by me. My must-see TV had become a new show called The Rookies, which ran on ABC from 1972 to 1976 and was sort of The Moderate Squad ÔÇö three cops in Southern California, two white, one black, all under the supervision of a gruff but supportive older (white) officer. One of the white cops ÔÇö the sensitive one, naturallyÔÇöwas played by Michael Ontkean, whose slightly injured air, dark curls, and black-coffee-colored eyes mesmerized me. (Even now, I can report feeling a twinge of sorrow, admittedly mixed with relief, when I discovered that the series does not stream.) Every Monday night at 8 p.m., I would watch, hoping that the episode would be about his character Willie, still not knowing precisely why, but aware that what lay beneath that desire was private and indefinably embarrassing. My father would watch with me; although the series was probably too humorless and melodramatic for him, he was just happy that I liked a cop show. By then, my understanding of the police ÔÇö that they were heroes who got it from all sides and whom nobody really understood ÔÇö was entrenched and reinforced by everything I saw.

Was there anything in my life ÔÇö my actual life, the part not lived on the carpet in front of a TV set ÔÇö to contradict this? Not yet, but my world was changing. The great cratering of New York City was now at its most dire ÔÇö it was the era of overflowing trash cans, of sidewalks full of dog turds, of garbage men on strike and blaring horns and headlines about financial default (ÔÇ£New York City Is Now DeadÔÇØ stories are not an invention of 2020), of graffiti-covered subway cars and mimeographed notes sent home from school about how to teach your children to protect themselves against muggers. I was still too young for some of the movies ÔÇö The French Connection, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three ÔÇö that reinforced the national image of New York as an ill-tempered hell where everyone was sweating just to get through the day. But my father took me to a couple of long-forgotten cut-rate versions of those films ÔÇö Cops and Robbers and Law & Disorder ÔÇö that played in our neighborhood. And around that time, worried that I was weak, he sent me to ÔÇ£self-defense school,ÔÇØ a private karate class run on Saturday mornings by a florid, bloodshot ex-Marine who lived in a grim, hoarderish room over a shoe store. It smelled like scorched coffee and damp paper; stacks of yellowing bodybuilder magazines leaned against the walls. ÔÇ£If a couple of bigger kids come at you to take your money,ÔÇØ the teacher told me, ÔÇ£hereÔÇÖs how you crush their windpipes.ÔÇØ I was extremely small for my age; it didnÔÇÖt seem likely that I would pull that off.

But I kept going back. If my father and I could find any common ground, it was this: I wanted to be streetwise, and he wanted a streetwise son. (Different streets, I would realize much later.) The police shows that were now on the air were one of the increasingly rare patches of neutral turf where we could meet. These werenÔÇÖt like the earnest series IÔÇÖd watched a couple of years earlier. The new ones ÔÇö Kojak and Baretta were my fatherÔÇÖs favorites ÔÇö were set in New York City, and, more than that, in a New York City that felt recognizable, where the sky was always gray, everyone was a dirtbag, a hustler, a wise guy, a shouter, an asshole, and cops were, as Joseph Wambaugh called them, the ÔÇ£new centurions,ÔÇØ working thanklessly to keep the streets of a modern Rome from running with blood.

Kojak, it is worth noting, had started as a TV movie set in 1963 that was explicitly about the racist framing of a young Black man for the rapes and murders of two white women. When it was turned into a series a few months later (you can stream seasons two, three, and five on Amazon), it was updated to the then-present ÔÇö the fall of 1973 ÔÇö and its sense of social conscience became considerably more intermittent.

Occasionally, one of these shows would have an episode about police brutality or a dirty cop. But unlike the 1973 movie Serpico, which concerned itself with systemic corruption and cast a long shadow over the police storytelling that followed it, the ÔÇ£systemÔÇØ in these series was depicted as flawed but essentially sound. ÔÇ£Not all copsÔÇØ was the baseline ethic of shows like Kojak; they would occasionally critique a policeman, but not policing. These series were ÔÇ£knowing,ÔÇØ they were savvy, and their cynicism seemed to spread in all directions at once. The vibe was, WeÔÇÖre not gonna pretend that some criminals arenÔÇÖt Black, and weÔÇÖre not gonna pretend that some cops arenÔÇÖt racist, and most of all, weÔÇÖre not gonna pretend that this is a nice place to live or that anything about it can be fixed.

This felt like significant news; when you reach fourth or fifth grade, nothing feels truer to you than the first pieces of pop culture to convince you that what you were told before was a lie. In real life (as seen on TV), there was no Officer Jim Reed, there was no Mod Squad. There were only the fed-up smirks of big, bald Telly Savalas and squat, menacing Robert Blake, trying to buck the higher-ups or to keep the savages at bay, depending on the story line. The best you can hope for, these shows argued, is that we all live to fight another week, thanks only to incremental justice or to the fundamental decency of one cop with his own moral compass. Watching them, I felt armed with the lowdown about how the world really worked, about how cops were the only thing standing between chaos and more chaos. I had still never met one in real life.

My father was, by then, always mad ÔÇö about Nixon, about Ford, about the stock market, about whatever sonofabitch was trying to screw him over, about the fistful of pills he had to take every morning. But cop shows seemed to make his own fury more palatable to him; they reflected back his view of the way things were, the only way they could be, in one hour, four acts. One July night, we were all watching Baretta together when the TV image suddenly reduced to a silvery dot, then blinked off. ÔÇ£God damn it,ÔÇØ my father said. Then the lights went out in the living room. ÔÇ£God damn it,ÔÇØ he said. We looked out the window just in time to see all of New York City go dark.

By then, it was 1977. I was 13, and our moments of untroubled family unity had become rare enough so that each one was memorable to me. I had drifted away from police shows and toward Norman Lear sitcoms that I watched on the black-and-white TV in the next room. And I had also drifted away from my father, who seemed often not just to be angry but to be angry at me ÔÇö whoever I was, whatever I was. He was dying of heart disease by then, although I didnÔÇÖt know that and IÔÇÖm not certain when he did. We fought a lot ÔÇö about the length of my hair, about my attitude, about how I never listened, about what I liked and what I didnÔÇÖt. I only learned later that around then, he said to my mother, with both desperation and determination, ÔÇ£I need a couple more years with him. Do you think I have that?ÔÇØ

We did not have a lot of father-son bonding experiences, but there was one night that year, during the time he was still healthy enough to go to work, when my younger brother was away on a school trip and my father decided that we were going to have a night together. I took the bus to his office in midtown, and he took me out to a chain steakhouse for dinner. By then I had become intensely interested in movies, and he had started to take me whenever he could. Next to him, I watched One Flew Over the CuckooÔÇÖs Nest, Network, Rocky, Dog Day Afternoon, and Jaws, and I knew that my love of movies was something he uncomplicatedly enjoyed about me, one of the few enthusiasms we could share without tension. For all of our mutual frustrations, my father was never uninterested in me; when he said, ÔÇ£WhatÔÇÖs on your mind?ÔÇØ he wanted to know the answer, even ÔÇö perhaps especially ÔÇö if it was something he hadnÔÇÖt considered himself. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm never going to yell at you for having your own opinions unless itÔÇÖs about your safety,ÔÇØ he said, and on that, he was usually as good as his word. That night, he walked us down into the not-yet-refurbished Times Square and bought us tickets to a cop movie: The Enforcer, the third Dirty Harry film. It was the one in which Harry gets a female partner. I watched the movie and was mostly interested in Tyne Daly, chasing criminals in a sensible skirt and wool jacket while carrying a huge shoulder bag. At the end, she took a bullet and died, to HarryÔÇÖs mild but not overpowering distress.

I had not seen it coming. I walked out of the theater somehow crestfallen, and my father looked at me for a long time. ÔÇ£YouÔÇÖre sad,ÔÇØ he said. ÔÇ£Are you sad because of the movie? ItÔÇÖs just a movie.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt know why IÔÇÖm sad,ÔÇØ I said, because I didnÔÇÖt.

We walked in silence for a while, and then he said, almost to himself, ÔÇ£My sad son.ÔÇØ He stopped talking again, as if he were working through something for which my presence wasnÔÇÖt fully necessary. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs all right,ÔÇØ he said finally. ÔÇ£You can be sad. It just means youÔÇÖre sensitive.ÔÇØ I remember that word, and the lightning flash of feeling that a door of permission had briefly opened ÔÇö a door I had no idea how to walk through. We didnÔÇÖt say anything more.

A year later, he was dead. As a teenager, I tried to numb my memories of him; feeling nothing seemed like the only way to survive. And yet: Sensitive. The word stayed inside me, like a latent virus that could flare up at any time. For a few years, I did not watch police shows, or go to police movies; it wasnÔÇÖt a conscious decision but rather a sense that they belonged to a childhood that now existed in a distant, simple past across an unbridgeable chasm. There would be no more crushes on TV policemen, no more yearning for the sensitive men with badges, no more imagining that under their calm and authority, they might be like me. They were there to maintain stability and control ÔÇö the things I wanted more than anything. But now that my world had spun out, that spell had been broken. They couldnÔÇÖt do anything for me anymore.

Yet they had left their mark, and despite whatever conscious work I do to erase it, I know it still lingers. It is humbling ÔÇö at least, it should be ÔÇö to come to understand all of the ways in which one is a product of oneÔÇÖs time. During this season of horror, I have often thought about children who are watching TV (or YouTube), and about how little distinction there is, when youÔÇÖre very young, between scripted, created, carefully manufactured imagery and actual news; itÔÇÖs all news at that age. The policemen who shove an old man or a young woman to the ground, then pass by indifferently as their heads bleed; the cops who kneel on a manÔÇÖs neck as he begs for his life, the ones who pull down a protesterÔÇÖs mask to pepper-spray him and who shoot rubber bullets just because they can, the one who fires not once into a manÔÇÖs back but seven times: Those videos, with their fragmentary, abrupt documentation, are the police shows on which a generation of children will be raised. These are their cops, not the men on Blue Bloods or Chicago P.D. or The Rookie or whatever people 50 or 60 years their senior are watching for the sake of nostalgia, comfort, or reassurance. They will have far less na├»vet├® to lose, or to fight, pointlessly, to preserve.

And they will not have to work to erase the lies they had the luxury of telling themselves. After my fatherÔÇÖs death, I rarely thought about law enforcement at all until eight years later, when, finally, I met my first cop face to face. It was the dawn of the crack era; I was a 22-year-old who had experimented hungrily with cocaine and was now experiencing my first panic attack. After calling 911 and explaining that I was dying, I was visited by a white officer and a Black paramedic. ÔÇ£YouÔÇÖre fine,ÔÇØ the paramedic said, looking at me with searing, fully earned contempt. ÔÇ£We see four of you every night. You wanna go to the hospital, IÔÇÖll take you. But a doctor will tell you the same thing.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£Or,ÔÇØ the cop said, ÔÇ£maybe you wanna come up to Harlem with us and see what kind of animal youÔÇÖll turn into if you keep doing this.ÔÇØ I did not. I had learned my lesson. And of course, I didnÔÇÖt doubt for a moment that he was there to protect me, including, apparently, from myself. As embarrassed as I was, I felt completely entitled to that protection. Even as I sat on the couch, my heart racing and sweat pouring down my neck, listening to the officer administer his reprimand, I didnÔÇÖt feel worried that IÔÇÖd get arrested. I had been taught very well. I knew how this worked. I wasnÔÇÖt one of the animals. How could I be? I was one of the good ones.