Darwin told us that danger hastens change — gazelles get faster because the lion gets faster first. So while it’s a terrifying time to love the theater, at least on the (bleak, Darwinian) side, we do get to observe the changes in live performance as it evolves. For decades, artists have been working out how computers and social-media operate onstage, but it wasn’t as if theater needed the internet for survival. That’s changed. The gazelle of remote performance just took a little leap.

To try to understand the evolutionary process, I talked to the makers of the online show Circle Jerk, a notable success at finding a new third way between the forms that used the mechanics of broadcast to increase (rather than diminish) theater’s stagy, greasepainty, sweaty essence. Combining lessons from live television filming, advances in technology, and an extremely online sensibility, creators Patrick Foley and Michael Breslin made a show that could be a model for others. It was also a shocking success: 5,557 people bought tickets. How’d they do it? Here’s a practical ten-step guide, complete with budgeting and blueprints.

STEP ONE: Start out with a long development process already behind you. Oh, did you not do this already? Foley and Breslin started developing Circle Jerk in May 2019 through the Off–Off Broadway theater Ars Nova’s Makers Lab. Last year, the group got six weeks of dedicated residency time with Ars Nova, which culminated in two public showings of what was then an in-person theater piece. Confident they had built a functioning show and intent on producing it before the election, they acquired a producer (Caroline Gart) and an angel (Jeremy O. Harris), and began lining up a theater in the Village. Contracts for their July 2020 run arrived in March … two days before the shutdown.

STEP TWO: Get a deadline. For a while, they just absorbed the shock. “We didn’t talk about Circle Jerk for a while because none of us knew what to do. And we were just trying to be kind and friendly to each other, and be friends instead of colleagues,” says Gart. To revive the show’s hopes would mean converting it into a completely online project, part film, part production. In June, they restarted the cold engine. The election gave them an end date, since the piece was explicitly political — it calls out white gay men’s complicity with white supremacy — and a deadline focuses the mind.

STEP THREE: Nail down your inspirations. Michael Urie’s early in shutdown apartment revival of Buyer & Cellar galvanized the group. In April, Urie and his team used multi-camera sitcom strategies, shooting on two iPhones, which allowed for close-ups, shifts of perspective, and wide shots. That discovery “opened up the vocabulary of what the first two acts would be,” says Breslin. He talked to his collaborators and David Bengali, their video and lighting designer, about exploring that same visual language. “Our first act feels like a farce or a Molière play, so what’s the cinema language of that online? We got to the three-camera, sitcom-y kind of thing.”

When it came to creating the aura of the Always Online, they looked to YouTube for models. “The big one,” says Breslin, “is ContraPoints, the YouTuber. She does these huge, queer, baroque long-form videos. She doesn’t usually do them live, but at least aesthetically, we felt that look is both doable and theatrical.” The Circle Jerk group, which includes dramaturg Ariel Sibert and performer Cat Rodríguez (also a dramaturg), had been thinking about “the interaction between live human corporeal performance and media technology” since forever, says Breslin (also, if you can believe it, a trained dramaturg). “One of the things during this whole pandemic that frustrated me was people being like, ‘How do we do this online?’ And Liz LeCompte [of the Wooster Group] and Marianne Weems [of the Builders Association] have been doing it for a really long time! We can look to people — women! — who have done it before.”

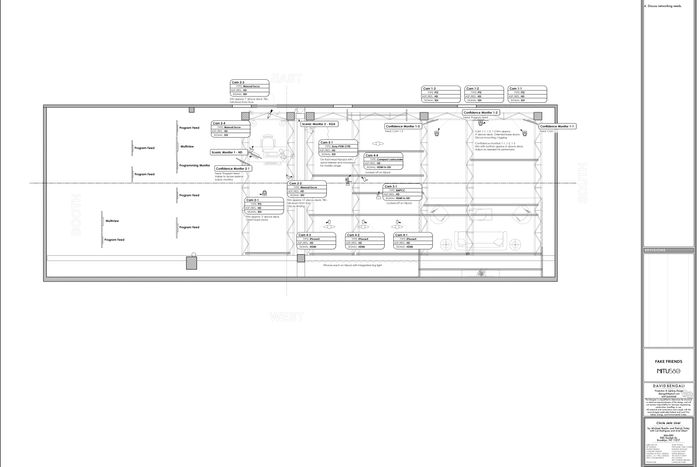

STEP FOUR: Embrace your technology. There were long conversations about what cameras they should use. Circle Jerk needed to show full bodies — the static Zoomography of most online theater simply wouldn’t cut it. Breslin brought up PTZs, pivoting cameras that can pan, tilt, and zoom (hence the acronym) and can be programmed to be remotely operated. “Once we found those cameras and David Bengali said, ‘Yes, this can work, and I’ve worked with these before,’ that’s when we started to lay out the set and figure out how the piece could live in meatspace,” says Foley. This was not DIY — they hired two video engineers. “It does take some sweet time and people who actually know how to do it,” says Breslin.

STEP FIVE: Budget. The all-in cost of Circle Jerk was around $87,000. They got a commitment from Harris for 65 percent of the budget, then raised the rest. During fundraising, people from both the theater and film worlds expressed doubts, but the extension brought in enough cash that the team was able to distribute some bonuses. They didn’t, though, recoup their costs. Given the immense effort and the tiny return, another show under the same conditions wouldn’t be possible, but Circle Jerk’s success has meant that doors (and wallets) are open now that weren’t before.

STEP SIX: Select a theater. The team went to Theater Mitu’s MITU580 space in Gowanus. Why? It’s flexible; it’s been customized for remote theater (because the seats were taken out this spring); it has upgraded livestreaming capabilities. And “Oh, yeah. My husband runs that theater,” says Gart. (He’s the co-artistic director of Theater Mitu and the space’s manager.)

STEP SEVEN: Find your online venue. The platform is important. The team toyed with using the gaming site Twitch, but they felt its ambience wasn’t right. They junked the idea of YouTube for logistical and moral reasons: “A lot of the alt-right stuff is perpetuated by YouTube’s algorithms, and we were not on Facebook for similar reasons,” says Breslin. “And then because the show is so referential [it’s full of audio and video samples]: A lot of these platforms have AI bots that stop your streaming if the audio goes over a certain length of time.” They chose Vimeo, hosted on a Squarespace web page, for its high video quality and its embeddability. Theaters and producers take note: Embedding video on your own website smooths and unifies the audience experience.

STEP EIGHT: Approximate the danger of liveness. The three performers rehearsed with director Rory Pelsue (Breslin’s boyfriend and Sibert’s roommate) — they formed a pod and quarantined, so all five could be in a room together. (Only at tech did the performance pod and the tech pod merge, and even then, only in a socially distanced group of around a dozen.) To learn to work with cameras that weren’t there yet, they memorized a precise set of stage movements, with stage manager Codey Leroy Butler clapping and shouting out the camera changes. (“Like a Suzuki class!” says Foley.) Once they were performing, they knew they wouldn’t be able to deviate from the choreography, since all 13 cameras were preprogrammed. Standing in for the zing of improvisation, therefore, was precise pacing and panic. The actors performed a variety of roles, whipping in and out of complete costume and wig changes, racing between two sets — a blue velvet living room and an ooky basement lair. “Performing it actually feels very, very similar to in-person performance,” says Breslin, “because it is so task-based and so task-oriented. There were so many marks to hit, and if you were one inch off, you were out of frame. So it was a technical task that felt not very fun in some ways, but also very nerve-racking in others.”

STEP NINE: Make (and keep) mistakes. There were several pretaped components of the otherwise live broadcast — like visits from an Internet Troll, who looked like a Cirque du Soleil clown at the end of a long weekend on angel dust — but even those were done in single takes, flubbed lines and all. The one-and-done approach was “100 percent a dramaturgical value of ours,” says Breslin. “If it gets screwed up, that’s part of the energy.” The team discussed the work of Christopher Grobe, a performance-studies scholar, who wrote about this summer’s virtual Democratic National Convention. Remember the lovable and janky roll call of the states? Grobe pointed out that awkwardness lends prerecorded material the sense of being live, and that sense of liveness, in turn, lends authenticity. Even with state-of-the-art cameras swiveling busily on their little bases, mistakes made sure there was a downtown, this-is-real vibe.

STEP TEN: Stay loose. Despite all their planning, some elements of October’s online ticketing wound up being worked out at the last possible moment. Each night of the run, Gart and Sibert were hand-entering ticket requests till the last possible moment. When we spoke, the team was still shell-shocked from what they (fondly?) call “the Eventbrite fiasco of 2020,” a brush with disaster during the run when Circle Jerk’s log-in links weren’t sent out in time. The group talked for hours about when they would cut off ticket sales, but eventually they “had to let go of our fear of people passing the password around or people entering our show without paying,” says Gart. “There’s a certain amount of control that you don’t have, which is maybe just the internet.” And giving up control is its own reward. “I do have to say, this process has been amazing, but the performance-week experience of it … I’ve never been filled with so much anxiety,” says Foley. “Every day, waking up being like, I’m gonna die today. I’m gonna die today. I’m going to be canceled, like, my career’s never going to even take off. And you know, then we’d go to the theater, and doing the show is actually the most useful fun time.”

Personnel: $32,000 (creative, production, hourly labor)

Production costs: $30,600 (video, sound, lighting, costumes, scenic, props)

Misc. production: $12,942 (production overhead + transportation + theater rental)

Overhead/administration/marketing/taxes: $11,583