Listening to Freddie Gibbs rap is like watching a running back score a hundred-yard touchdown on a kickoff return. He locates pockets that shouldn’t be there, speeding forward with poise and precision that make it look easy, even joyful. If you’re a fan, you know that the chops that made 2014’s Piñata and 2019’s Bandana, with elusive West Coast indie-rap icon Madlib, and last May’s great Alfredo, with veteran rapper and producer Alchemist, were present as early as 2008’s midwestgangstaboxframecadillacmuzik and 2010’s Str8 Killa (run back “Sumthin U Should Know” and “Rep to that Fullest” for proof). But it wasn’t until well into the 2010s that hip-hop heads at large recognized this; it wasn’t until last November that a major music-award show took notice. Alfredo’s nod for Best Rap Album at the 2021 Grammys (alongside new releases from Nas, Royce da 5’9”, and Jay Electronica) has got the 38-year-old Gary, Indiana, rhymer reflecting on the peaks and valleys of his nearly two-decade career, from signing to and summarily getting dropped from Interscope Records in the early aughts, to the promising work relationship with Jeezy’s CTE World imprint that fizzled out badly and publicly a decade later amid differences of opinion regarding the direction of Gibbs’s career, to gaining the trust and friendship of legendary beatmakers, to sparking the ire of chatty cultural commentators.

Speaking over the phone in mid-December, Gibbs is an intriguing mix of confident and humble. He’s grateful for and excited about the recent accolades for his formidable catalogue. He’s also plotting moves for 2021 that’ll carry his gifts as a wordsmith and a side-splitting internet humorist in his videos and social-media accounts into new fields of play.

Alfredo made a lot of lists of the best music of 2020, and you were nominated for your first Grammy for Best Rap Album. What’s your mood?

Oh, man, it’s surreal. I wake up every day, and I’m like, “What?” I got to look at it every day to believe it. Obviously, everybody feels like they should be nominated for a Grammy for something that they do that’s received well, but I never thought that I’d actually get nominated, especially for an album like Alfredo. So, I’m grateful.

It came out right when all the protests were jumping off and touched on the same kind of revolutionary mind-set. Do you feel like we’re any closer to better circumstances for Black America than when 2020 started?

No, not at all. We got a new president, I guess, so, he’s going to have to take it from there. I don’t really see how you can change 400 years of injustice in a year or two. It’s going to take a while. There’s a lot of things that are going to have to change, not just police brutality. That’s the media focus, but it’s a lot of things. You got to bridge the wealth gap. Until that happens, it’s still going to be the same type of people in power.

I agree, but on another level, in four years, this country nearly turned into a dictatorship. They tried to end democracy. That makes me wonder whether it’s actually that hard to change things or if people are just not willing to.

I’d say that people [are] not willing to. When you got certain people in power, it’s going to be tough to make changes in the way this country is ran. Been difficult, man. I take everything any politician says with a grain of salt. For one thing, nobody in the [2020 presidential] campaign talked about reparations for Black people. Every group of people that went through [similar] injustices like slavery, I feel like there were whole generations that were taken care of, but I don’t see that with us. And it’s not just a money thing. It could be a tax thing, an education thing, some type of boost toward the development of Black people.

A lot of people say you’re the best rapper out right now. For the last, like, seven projects in a row, you’ve been melting our brains with flows and wordplay. What kind of practice does that take?

I wasn’t as good of a rapper [in my early work with Alchemist]. Back then, I was still sharpening my sword. Now I know where I’m at lyrically, musically, emotionally, all of that, when I go in and make songs. I kind of zeroed in on all of that. Really, it’s just studying the game, seeing where the game is at. Trying to be in the mix of the game, but not blending in, if that makes any sense. I gotta be in it, but I can’t be the same as my peers or guys under me. I got to take things from what they do and pay attention to them, or I’m just ignoring the competition. If everybody in the NBA got a Euro step, and you ain’t got one, you kind of fucked up. So, that’s where the versatility comes into play. I listen to everything so it gives me a better sense of what I should do. If everybody’s going left, I’m gonna go right.

For the last handful of projects, you stuck with just one or two producers. Do you feel like that makes for a more cohesive project?

It depends. I was real fortunate to be able to work with Madlib and Alchemist. I feel like you gotta really work very hard to even get in a room with those guys. So I put in the work to get there, and once I got there, I made the most of it. Those two guys really made me a better rapper than I was before them. They challenged me, and I accepted it and stepped my game up. I had to step my game up to do a project with both of those guys. All of these things are related. If I didn’t do Piñata and Bandana, I might not have done Alfredo.

It’s not just that you work with Madlib and Alchemist, who are kings of a certain strain of hip-hop, because you’ll also go and do a track with Hit-Boy, and you’ll do records with Kenny Beats. Not everyone can hang with both the boom-bap stuff and the trappy stuff.

That’s the mix. That’s why I think I’m the best. Because I can do all of that stuff. I can do a lot. It’s not nothing that I can’t tackle. I’m not going to spread myself thin. I’m not going to try to emulate somebody else. I could fit in. I could bring Freddie Gibbs to any world. That’s what makes it all special: I could do anything, lyrically, that I want to do.

What kind of thought process goes into picking beats?

[I like it] if I feel like my voice would sound good on it. And sometimes when I’m working on a project, like I just did with Alfredo, the beat-picking strategy might be a little different because I’m trying to make everything cohesive and fit together correctly. I think those little details are what puts you in Album of the Year lists, and puts you in the Grammys and things of that nature. We kept it simple but complex at the same time.

Are you involved in the production process at all or are you just kinda picking beats and then letting the producer take the wheel?

I’m like Diddy, man, the whole situation. I’m like if Suge Knight rapped.

Wait, elaborate!

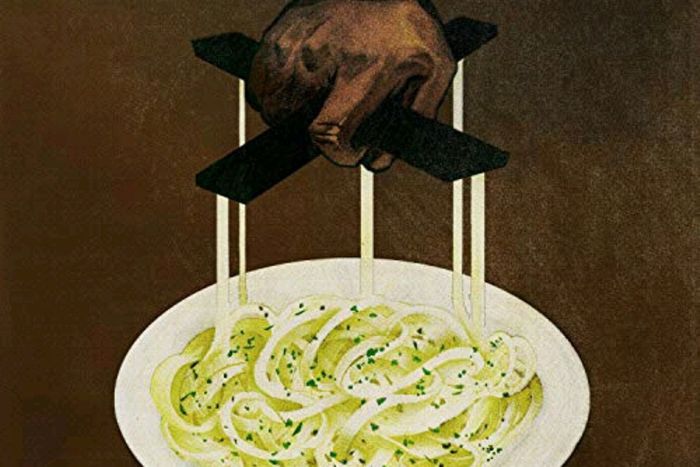

[Laughs.] I’m picking everything. I put it all together, the producers, everything. I might not play the drums and I might not do nothing like that, but I’m pulling all the strings. I put the Alfredo theme together. That’s why you see that black hand [on the cover]. The strings and the pasta. Black man winning and in charge. That’s me, man.

How’d you even get Madlib to do a second collaborative project? Most people are lucky to get even one.

Man, I rap the best; he couldn’t deny me. During the first one, me and Madlib really developed a great relationship, a real tight bond. So it was deeper than just making music at that point. It was like a family-type thing. So it worked out for the better. We a team. I look at all of us as one big family. I’m sharing this [Grammy nomination] with Madlib, too. He set the precedent with those albums that he did. They made me and Al step our game up. We always give it up to Madlib.

A lot of fans got onboard around Piñata, but you’d been rapping and putting out great projects long before that. Does it make you a little nonchalant about accolades, knowing that a lot of people need to see other people paying attention before they get in the mix?

No, man, I’m thankful for every new fan, every new person that comes to my music. I’d be tripping if you didn’t want to call and interview me. I can’t say that I necessarily make music for the accolades or for the awards or for the attention. I do it because I love it, and the people that love me love it. So my main thing is to satisfy my fan base. And as long as I keep feeding them, I’ll be happy. I can take care of my family and do what I got to do.

Growing up in Gary, Indiana, how did that upbringing formulate your perspective on life? A lot of people who don’t know the Midwest — and I don’t know the Midwest all that well— hear of Gary, and we know you, the Jacksons, and that’s the end of the story.

Gary’s a tough area. It’s right by Chicago. It’s a blue-collar town, steel-mill town, predominantly Black. That’s how it was when I was growing up in the ’90s. For the most part, it’s a tough town to grow up in, and you gotta have a heart to stick it out and grow up, to come up out of there. Anybody that’s from there will tell you the same thing. I bring that blue-collar mentality to everything I do, my work ethic, everything. My mother was a postal worker for 30-plus years. She ain’t never take a day off. I look at the things that she did, all the work and overtime she put in just to keep the household stable. That’s definitely an influence on everything I do. It’s a Gary mentality.

There’s a point in the 20th century where the Black population in Gary triples in just a few decades, presumably because white residents picked up and left when factory job prospects dried out. It seems like the same story all over the country, cities being neglected when the white population disappears. It’s the story of the inner city in New York, too.

They dry it out, turn it into the Rust Belt, make it fucked up, and then they get it fixed and gentrify the shit. In 20 years, Gary will probably be all condos or some shit. It’s right on fucking Lake Michigan. Real talk, man. That’s how they do, man, divide and conquer, dog. I just want to carve my little piece of the earth out and raise my family, man, wherever that is. I’ve been traveling a lot, so I’m kind of on a global wave in my thinking right now. I’m in the process of buying property overseas. I ain’t even thinking just America no more.

It’s probably a good time for people who have the means to get out. The place is cashed. People overseas are getting back to their lives, and we can’t even sit inside bars.

If I could pick up everything and go right now, I would, but I got a job to do. I gotta rap.

Did you just stockpile music all 2020? What have you been up to? Usually you jump out on a tour after the record, but that hasn’t been possible.

That’s been kind of wild. The album’s been doing well and I’ve just been in the studio. I’m renovating my house. I rebuilt my studio. Nothing crazy. I been chilling. We can’t really do nothing. I just got off vacation. I went to the Dominican Republic, and that was cool. I went to Miami. Anywhere that’s open I kind of go to, staying safe, though. I was in New York for a month. We took the time and shot a movie. I made the most of it. I’m going to the Grammys [Ed. note: The Grammys were postponed to March 14 after this interview; it is currently unclear who will attend]. It was a down year for America — a tough year for all of us — but a decent year, workwise, for me.

What’s this about a film? Can you share any details?

No, not yet. I’m naked in there, though. I’ll just tell you that. [Laughs.]

Over the summer you signed with Warner after being independent for a few years. You haven’t had the best time with major labels. What makes this situation different?

The one time I was signed to a major label before [Interscope], I was just a kid. I didn’t really know nothing. Nobody knew me. I didn’t have leverage. This situation was different because I’m me now. I got more control. My talent level is higher than it was then. I can do more now, I know the business a whole lot better, so I can make the situation work for myself. They see value in what I do and I see value in what they can bring to the table. I think it works out.

Do you wish there was a better understanding of how much time it can take to make music a good-paying job?

I don’t know. I never worked hard to get signed. I got signed after probably a year or two of even rapping. I didn’t really know what that was to be signed or none of that. I got dropped in six months. That shit came and went very quick. I had to learn how to become my own machine. My path to where I’m at is very unique, probably quite different than a lot of other people. I had to fall flat real quick, and then learn how to take some years and time and a whole lot of effort to get where I’m at. If you would’ve told me 10 years ago that I was going to have to wait 10 years to be Grammy nominated, I don’t know if I would have kept rapping. But that’s me and my young mind. I would have been like, “Damn, I got to do this shit 10 more years?” The years in between are all learning years. I wasn’t ready for the stage that I’m on right now, back then. But now I’m ready for it.

People are too impatient to appreciate the slow burn. It’s pass or fail now.

Motherfuckers feel like if they don’t make it by 22, they dead. I’d rather have it later in life than get it quick and then lose it all. I know a lot of rappers that were popping 10 years ago when I was trying to get it popping, and now they gone. A lot of those guys probably can’t go do a show nowhere; a lot of them probably don’t own their masters; a lot of them probably ain’t getting no money off streams or whatever; a lot of them probably signed with somebody who can’t put out a project. It’s all about longevity for me.

Jeezy mentioned your name on the song “Therapy for My Soul” from November’s The Recession 2. And you’ve said that you felt like he was drumming up controversy to sell albums. Will the air ever be cleared between the two of you?

Maybe. Maybe. I don’t see it as a big deal. Ain’t nobody dying. Nobody get shot. Ain’t nobody get hurt, so it ain’t nothing like that.

Sure, but “Real” is one of the rudest diss tracks of our time …

I was more hurt than anything. That’s what it feel like when one of your favorite rappers gets at you like that. I think that he see where I’m at now, and then he looks back at that shit, and he regrets it. I don’t say I regret nothing. But it’s better ways I could have handled things with him, maybe talked it out and communicated better. Maybe it could have worked out. I don’t have beef with him like other people may. I think it was just two guys who didn’t communicate correctly. He had a vision, and I had my vision, and we just couldn’t come to a common agreement. I don’t hate the man or anything of that nature, not at all. At one point, I looked up to him. And I still respect everything that he did musically. I still listen to his music. So, like I said, man, maybe one day, who knows?

Who won the Verzuz, though?

That’s a tough one.

I feel like I have to give it to Gucci just for walking in the room and doing all the old diss tracks face-to-face.

That was a little too far, man. I was like, “Damn.” Gucci one of my favorite artists, too. So both of those guys is trap legends. But, yeah, Gucci probably took that one.

Over the summer, DJ Akademiks, who went at you on social media over Jeezy, was let go from his position at Complex and admitted to contacting the police over Twitter beef with Meek Mill. I’m just curious if you have comments.

Good old Akademiks. The whole thing was corny. I just feel like certain guys like that, their opinion don’t really matter. Why are we even listening to a guy like this? How did he get on? Twitch? He not a DJ. I ain’t got no problem with the kid. I seen that kid one day in L.A. before all of this started. And when I tapped him on the shoulder, he was hella spooked. So he know what I’m about. Everybody know. Everybody that know me, know what a problem with me, what it comes with. I’m a cool guy. I’m a good guy. I don’t go around starting no trouble. I be chilling.

But you’re not one to let someone else start it up without getting a word in.

No, no, no, no. I got to have the last laugh. You’ve got to crush them till they eliminated. That’s just the way it got to go.

I talk to a lot of artists who don’t really care for social media, but you keep pure chaos and comedy going on Instagram and Twitter every day. How do you find that stuff?

At this point, man, people send me that shit. It’s the way I talk about it. I’m like the new Tosh.0. They want to hear me put my captions on the shit. They know I’m gonna speak the truth about shit and call it like it is. If you got a baldhead ass baby and they fall down the steps, I might put that shit up on my Instagram story [laughs].

What’s on your calendar for 2021? Is your song with Big Sean going on a project somewhere?

Comedies, man. Movies. I’m trying to do more film in 2021. I’m trying to do sports. I’m trying be like the ghetto Stephen A. Smith … not that Stephen A. ain’t ghetto, but a more thugged-out version of that. Music, I got that in the bag. I’d like to thank Big Sean for being such a giving, caring person. He’s one of the most lovable guys in the industry. Rich-ass nigga gave me a verse. I appreciate him. I got more where that came from. I just started working with Hit-Boy. Metro Boomin hit me. I’m ready to really go in.

So you might be back on a trap wave next year.

I’m going to be on a crazy wave of everything. People saying I’m the best rapper, and now I’m about to stand on it. A lot of guys are that great, but I think I bring a different kind of personality to the music, to everything. I really want to stand on that this year and have some fun with it. I’ve shown people that I know how to make classic albums. That ain’t no problem for me. Now I want to get into these Big Sean hit singles and stuff like that. Just jamming on the radio, maybe. If not, cool. I want to make some strip-club songs. Me and Wale are going to do some shit. I’m trying to work with Tobe Nwigwe. Niggas like that be inspiring me. Then I listen to a nigga like Future, and I’ll be like, “Oh, hell yeah.” Future’s probably my favorite artist, period. I listen to Future and 2pac every day.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.