Over the past few weeks, our collective pandemic brain has turned its attention to the High School Musical franchise, specifically its latest iteration, High School Musical: The Musical: The Series and its various melancholically vengeful constituents. Personally, not to brag, I have been thinking about High School Musical for 15 years. I grew up in the early aughts with two younger sisters who were the perfect age to be permanently ensnared by what was initially a three-part franchise — a bright, gently psychotic tale that centers on two star-crossed New Mexican teens named Troy Bolton (Zac Efron) and Gabriella Montez (Vanessa Hudgens), who cannot figure out how to do high-school theater, play basketball, be lifeguards, and also chastely date each other. As such, I am not only word- and note-perfect on every single song from all three films, but I also saw High School Musical 3 in theaters with my entire family, and, yes, all of us cried.

I’m not here, however, to discuss the evocative machinations of the third and final High School Musical film, a moving treatise on coming of age in George W. Bush’s post-9/11 America. I’m here to talk about a three-minute stretch from High School Musical 2 that has haunted me — and I mean that in a neutral but literal sense — since its 2007 premiere, which, incidentally, fell on my birthday and brought in 17 million viewers, more than any other Disney Channel Original Movie in history. The moment in question is a stunning microcosmic expression of the futility of the human condition, as performed by Zac Efron. It is both disturbing and unbelievably hilarious. It is simultaneously a nice shampoo for your brain and a cursed artifact that, like the video from The Ring, will permanently alter you. I recommend it as both a balm for whatever ails you and as a stark reminder that all of us are doomed to Hades.

First, a bit of background: In High School Musical 2, Troy and Gabriella and their friends all land cushy lifeguard jobs at the local Lava Springs Country Club (a thinly veiled reference to hell that will become important later), where, inexplicably, there is a staff talent show. Sharpay (Ashley Tisdale), Gabriella’s rich, blonde nemesis, attempts to incite tension between Troy and Gabriella by insisting that Troy perform with Sharpay in the lifeguard talent show; in exchange, she will ask her well-connected father to give Troy a more bougie summer job as a golf pro and also help Troy land a scholarship at the highly exclusive University of Albuquerque.

Troy, a smiley and sweetly dim teenage boy with nice highlights who thus finds himself in this sort of situation more often than not, takes the job and becomes fancy, subsequently alienating himself from his friends, one of whom is named Chad. Gabriella soon dumps him, returning the T necklace he gives her at the beginning of the film and singing a song about needing space. A spiraling Troy turns to his father, Jack Bolton, for advice, and his father, limited by being a man named Jack Bolton, tells Troy the answer is in Troy. The next morning at work, Troy learns that Sharpay has manipulated the situation even further, forcing his friends to work shifts at the country club rather than participate in the talent show. Now none of his friends will speak to him, not even Chad. Troy is bereft. You won’t believe me when I say this, but this was the shortest way I could figure out how to summarize this movie for you.

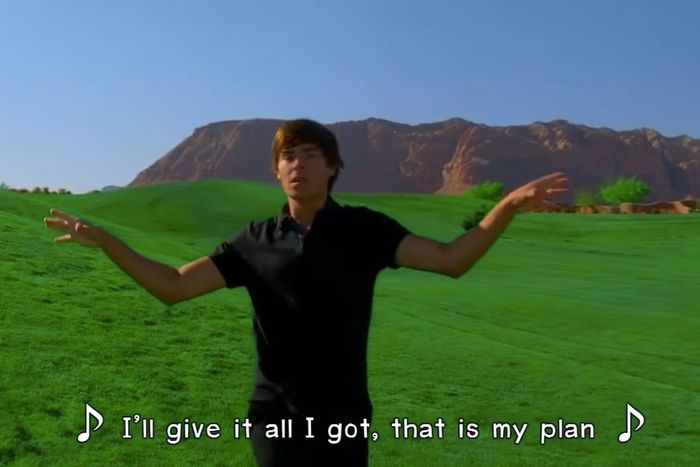

That’s when Troy returns to the golf course, the very site of his social devolution, for some difficult self-reflection. Wholly alone, clad in a black polo and dark denim no doubt absorbing and retaining the broiling midday Albuquerque sun, Troy begins to prance, with increasing fury, across the uncannily smooth greens. A tense drumbeat begins. Troy kicks out his left leg, briefly engages in a moment of sad jazz hands, and stomps gracefully but with visible rage. “Everybody’s always talking at me,” Troy sings, his face a grotesque mask of despair as his hands become fists, which he raises to his ears, covering them as if to block out the relentless noise of modern life. “Everybody’s trying to get in my head / I want to listen to my own heart talking / I need to count on myself instead.”

This marks the auspicious beginning of “Bet on It,” a song about the impossibility of free will that’s also one of the first Troy Bolton solo numbers Zac Efron was allowed to sing with his own voice, instead of having it quietly overdubbed in post. “I was not really given an explanation [from director Kenny Ortega],” Efron told the Orlando Sentinel of the overdubbing back in 2007, in a story “unearthed” by J-14 a full decade later and then covered by Teen Vogue as news. “It just kind of happened that way. Unfortunately, it put me in an awkward position.” In the second film, Efron explained, “I had to put my foot down and fight to get my voice on these tracks.” With that context in mind, “Bet on It” takes on an entirely new dimension. It is not only a song about a teenage boy plumbing the depths of the human experience on a golf course in New Mexico; it is also a song about Zac Efron doing the very same, about a young man pushing for control of his own destiny, “putting his foot down and fighting to get his voice on these tracks.”

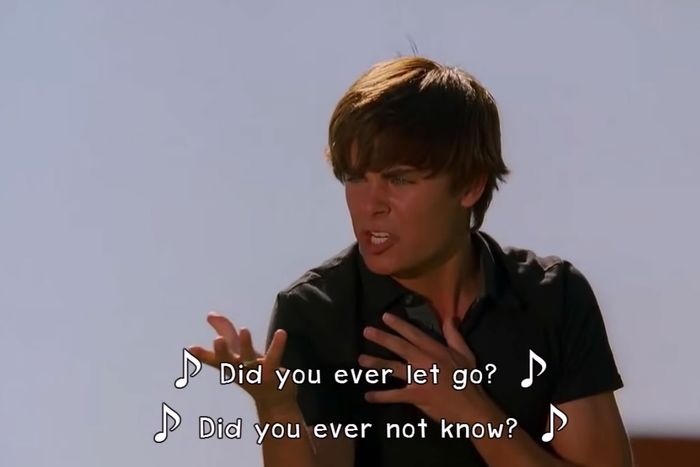

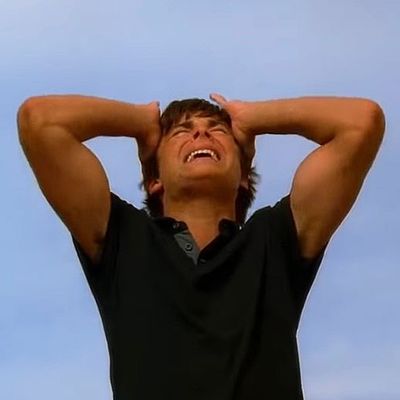

That meta layer is reflected in Efron’s commitment to the number, which is so intense as to be disorienting. Out of respect, I seek to match his intensity in this analysis. Watching the three-minute video, rife with popping forehead veins and clenched hands and ground-punching and flawlessly executed twirls, one gets the sense that, were Efron to commit to the bit any further, he would stroke out. But it’s that very intensity that makes “Bet on It” so compelling and, as I mentioned earlier, haunting, especially when set against the surreal, empty hideousness of Troy’s surroundings.

There is an unsettling chasm between Zac Efron’s earnest, full-bodied song-and-dance routine and the fact that he is performing this routine on a silent golf course surrounded by fake country-club desert, a setting notably artificial even within the hollow confines of the Disney Channel Original Movie Universe. Perhaps that’s how Ortega intended it: Behold this hopeless young man, trying to find his authentic, existential center in a contrived world where even the grass is shorn until it no longer looks like itself. By setting up this sharp contrast between plaintive human expression and the capitalistic mimicry of nature, Ortega suggests that Troy is — as is Zac Efron is, as are most of Ingmar Bergman’s protagonists, as are we all — set up to fail, fundamentally incompatible with the manufactured travails of modern life.

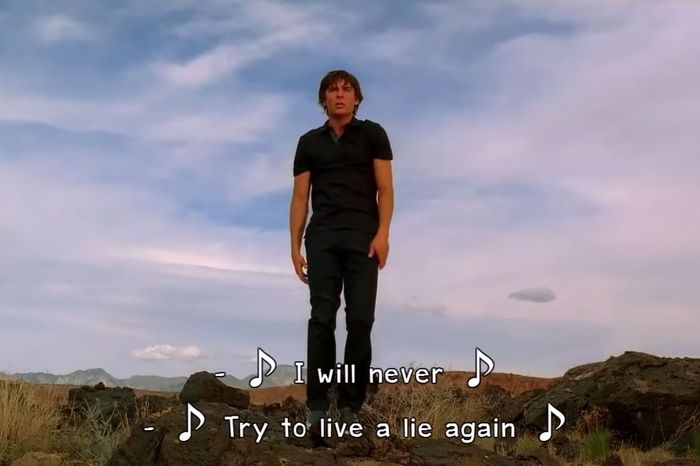

About halfway through the song, during which Troy becomes so distraught he kneels in agony, he wanders off the manicured grass into a rockier area populated by wilder-looking grasses — an area that appears achingly close to its organic counterpart, despite being just another forgery of the natural world. He is “out of bounds,” which I just learned is a golf thing. Troy holds his hand to his heart. “I don’t want to win this game if I can’t play it my way,” he sings wrenchingly, as if he understands he will be forced to play this game anyway, and he will lose. He hurls his body off one of the fake rocks and onto a pile of fake sand, which he then expels from his hands on beat.

But moments later, Troy finds himself, quite inexplicably, right back on the smooth golf course. At this point, it becomes clear to both us and to Troy: Troy Bolton is in purgatory (more popularly known as the Disney Channel). Like the characters in Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit, Troy Bolton is a damned soul among other damned souls, locked in a country club surrounded by shoddy imitations of the world they once lived in, where they will torture each other and themselves for all of eternity.

The camera spins around Troy, indicating that he is helpless, a mere fictional mortal unable to truly see or control his fate. His dancing becomes more manic, more furious. He beckons from over his shoulder for the camera to follow him as he reaches the bridge (of the song and of his life). “Ho!” he yells. “Hold up!” He looks at the sky as if, for a moment, he is able to glimpse and absorb his fate. Briefly, the music pauses. But Troy visibly shakes off the knowledge of his damnation and instead pulls a golf club out of a bag that has mysteriously appeared out of thin air — a fact he does not question, as he understands, on some level, that he is being puppeted by an unholy force beyond his comprehension (Kenny Ortega). As the sun sets behind him, Troy hits the ball directly into a manmade pond. He is visibly disgusted with his own limitations, his now plainly obvious dearth of free will and agency. “Gotta work on my swing / Gotta do my own thing,” he yells, hurling the golf club offscreen, where it disappears as quickly as it manifested.

Suddenly, it is midday again. Troy stares at his own reflection in the golf pond. “It’s no good at all / To see yourself / And not recognize your face,” he sings. “Out on my own / It’s such a scary place.” It’s here that Troy finally allows himself to digest the fact that he is trapped in limbo, a fictional invention in an endless stage play from which he will never escape. But just as quickly, he rejects this truth. He plunges his hands into the pond, shattering his reflection, and runs frantically, joyfully back toward the country club, where he knows he will be able to subsume his fresh, painful understanding of the nature of his reality. “I’m not gonna stop / Til I get my shot / That’s who I am / This is my plan,” he screams, doing his best Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music. He runs back to the fake rocks, where he strikes a defiant pose, his arms extended toward the heavens. “You can bet on me!” he sings, as if challenging the gods (Ortega) to contradict him.

But the camera zooms away from Troy as his voice echoes across the canyons, revealing that he is, indeed, still — and always — alone. The camera then cuts away; in the next scene, it becomes apparent that Troy has figured out how to leave the golf course and, at least temporarily, reenter the more populous areas of Lava Springs, where he apologizes to Gabriella and gets her back. The talent show goes off without a hitch. Nobody mentions having seen Troy stomp across the golf course, or that moment when he tried to prove he had wrestled back control of his own life, only to plop a golf ball into the middle of a pretend little golf pond.

At the end of High School Musical 2, the entire cast of the film heads onto the golf greens together, carrying glowing orbs, which they release in tandem into the “sky.” Troy and Gabriella smooch as fireworks explode in the “distance.” “Here’s to the future,” says Gabriela, laying her head on Troy’s chest. “No,” says Troy, looking at the painted horizon, his face anxious and pained as the camera fades to black. “Here’s to right now.”

More From This Series

- ‘It’s Everything I Love in One Place’

- The Renegades Who Made A Woman Under the Influence

- The Six-Movie Season That Turned Jude Law Into an Oscars Punchline