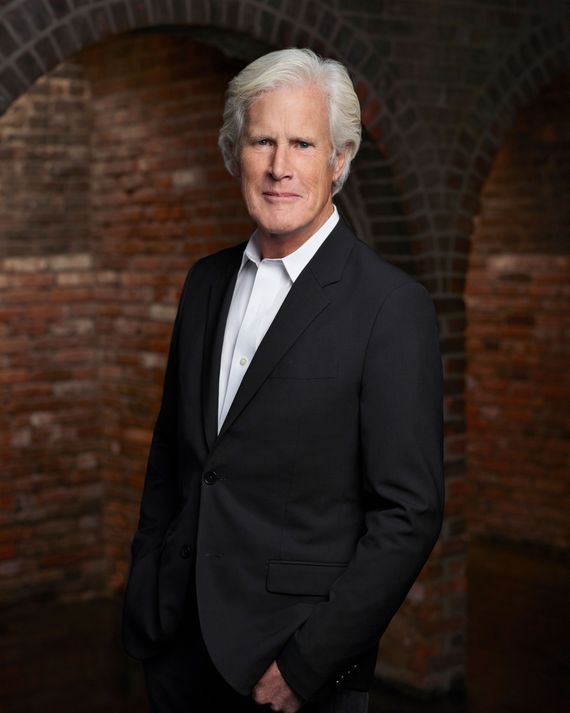

After more than 50 years in the broadcasting business, there are still some surprises to be had for Keith Morrison, the dulcet-toned correspondent of NBC’s long-running newsmagazine, Dateline. For instance, the success of his first podcast, 2019’s The Thing About Pam, which hit No. 1 on Apple Podcasts and will soon be adapted by Blumhouse Television into a limited series starring Renee Zellweger.

“I hadn’t given much thought to the podcast world because we were busy enough as it was,” says Morrison, who began his career in radio. “I was somewhat skeptical at the beginning that this would be such a good fit for us, but once you realize that you’re not constrained by all the structure of a television show, you can get more into the details and down the rabbit holes. It was fun.”

So fun, in fact, that Morrison has decided to do it again: His new podcast Mommy Doomsday follows the bizarre story of Lori Vallow, an Idaho woman whose two children went missing in 2019 and were later discovered dead on her husband’s property in 2020. The series, produced by Dateline and NBC News in partnership with Neon Hum, debuts February 16 with two episodes. (Check out the trailer here.)

Vulture recently spoke with Morrison about Mommy Doomsday, his initial reluctance about covering true crime, and the one case that he just can’t seem to shake.

When you sit down to review the vast number of cases Dateline has covered over the years to select one for the podcast treatment, what criteria are you looking for?

Keith Morrison: I think the principles of a good story are all the same … It needs a strong character who people are amazed by and want to hear more about. And also things that happen that you wouldn’t think could possibly happen. If you can allow people to imagine what might be coming next, and that what is coming next is really quite remarkable, then you’ve got a good story to tell. I’m just talking about it in terms of storytelling, the morality of these things is quite another matter altogether.

Is it just coincidental that the two podcasts you’ve done so far have centered around crimes perpetrated by women?

[Laughs] It is, totally. Although, I don’t know whether it is safe to say such a thing, but some of the most interesting criminal minds you run across are the women. I’m from Canada, and people used to say — and maybe still do — that “We don’t get as many murders in Canada, but they’re so interesting.”

For those who are unfamiliar with the particulars of the Lori Vallow story, what can they expect out of this podcast?

This is a story about a woman who had been having trouble getting stability in her life, who had kind of bounced from one thing to another, one husband to another, one difficulty to another. She’d always been a religious woman. She seized upon a religious crusade that would give her some real purpose in her life, but it went off the rails, and it left bodies in its wake. We’re still investigating just how many bodies that may be.

To your point, investigations are still pending, so her story really isn’t finished. How then do you craft a compelling conclusion for listeners?

I fully anticipate that there’ll be another trial before too long — and would already have been by now, had it not been for COVID. [Vallow’s trial for misdemeanor charges is slated for August 30.] So you can leave things in advance … as long as listeners or viewers kind of understand what’s what and who’s who and what happened. You don’t have to see them carted off to prison. It sounds so cold. It’s a weird thing. Can I back up for just a second?

Of course.

Getting into this line of work, this storytelling about true crime, was not an easy thing for me. I had covered all kinds of stuff for a long time in Canada and the U.S. — daily news for NBC Nightly News and the Today show and long-form documentaries on NBC, but also on the CBC for years covering politics mostly, but other stuff, lots of stuff, and I enjoyed it immensely.

And when true crime sort of took over the genre of long form in America, I was one of the early resistors. I didn’t want to do it. I just thought, What? It’s almost like you’re intruding into a process, which it’s our right to intrude and look into it and see what happened. But I wasn’t sure it was a good thing for us to do, necessarily. But as I have done it, it not only opens a window on human character, that is probably a uniquely suited way to get there. I don’t know of any other way to get to the heart of what makes a human being, a human being. To dive deeply into a criminal matter that a person has been involved in. And the victims of these murders or whatever they happened to be, the families of those people, we don’t talk to them unless they want to talk to us. If they want their privacy, we give them their privacy. But we find more often than not, they’re happy to do so. That it’s cathartic for them. That it’s a way to honor and celebrate the life that was lost. And so I feel better about it, but I will say, I never expected to be quite so fascinated about the many and varied facets of human behavior. How we’re all strange little ducks inside somewhere.

I feel like shows such as Dateline give viewers a level of transparency about the justice system that we maybe wouldn’t get otherwise.

Yes, I agree. I’ve learned lots of things about the justice system I wasn’t aware of.

You just celebrated your 25th year with Dateline. I’m curious if, in all this time, you’ve developed a BS meter for when people are lying to you?

Maybe to some degree. I was fascinated by the study that came out years ago on this very question. I interviewed this guy, and he’d done a lot of research, and the evidence shows that an average college student can detect lying with a somewhat better average than the average detective who’s been working in homicide cases. The research speculated that the reason for that is simply that the homicide detective thinks he can identify a lie, therefore he’s apt to make mistakes when listening to the answers. Really, human beings are incredibly good at lying and not very good at determining when they’re being lied to. I think that’s a large part of the reason people are so fascinated by true crime, because they are in a world where you don’t know who’s telling you the truth and you want to find out.

So would you say you’re in between a college student and a detective?

[Laughs] I’m probably the worst of those.

Speaking of your long tenure at Dateline, is there one case you’ve covered that stands out as the most memorable — one you just can’t shake?

There’ve been so many, there really have. The one I think about, it’s a story that really, nobody knows and hasn’t been particularly celebrated outside of classrooms where they teach about it in some universities. It was a case the Innocence Project took up and never got the result they were hoping for.

The case involved a man named Billy Wayne Cope, who lived in a small town in South Carolina. His daughter was murdered and sexually assaulted one night, and Billy Wayne had been in the house. He called 911, and they decided he must’ve done it. And though he denied it endlessly — 666 times, his attorney would later say — he eventually caved. He was not a terribly bright man, but he was a very sweet fellow. He was charged with the murder. He finally confessed. But a month later, they identified the DNA that was found in his daughter [from] another crime that occurred a block or two away from where he lived. And the person who was caught for that crime, it was clear as day that he also committed this crime. I mean, he left DNA in both of those people. But instead of absolving Billy Wayne Cope and charging the other guy, they charged him with conspiracy and tried them both, and accused Billy Wayne of helping him and watching, and being an even worse villain for that, even though they’d never met each other before. And so it was a total bogus case and he was convicted, sent away for life. All the efforts of all the Innocence Projects that got involved, because they wanted to free this innocent man, came to nothing and he eventually died in prison. So it’s a very, very sad story, but one that I can’t shake. I think about it a lot.

I’ve always been a fan of Dr. Seuss. One of my favorite books of his is Horton Hears a Who!, and the reason is because it exemplifies what’s good about the justice system. A person’s a person, no matter how small and is entitled to equal justice under the law. And that, I think, drives a lot of people who are in that line of work, that they would like to see justice achieved for everybody. And it’s a terribly imperfect system, but I think that’s the goal people have, and the thing that gives emotional heft to a lot of stories, like the one about Billy Wayne Cope.