Earlier this month, one of 2020’s greatest late-in-the-year releases earned a Golden Globes nomination. Wolfwalkers, from Irish independent animation studio Cartoon Saloon, is the beautifully rendered telling of a folkloric myth, centering on a very real and traumatic moment in Irish history: the destruction of culture, nature, and independence under English colonialism in the 1600s. It’s still a kids’ movie, though, so it’s also whimsical and fun, full of clever and soulful hand-drawn animations and voice performances, and some cliché-defying strong female leads. On the day of its nomination, we spoke to directors Ross Stewart and Tomm Moore.

Congratulations! How are you feeling about your nomination?

Ross Stewart: It doesn’t really feel real, I suppose because we’ve just been stuck at home, and everything’s virtual. If we had a big party with, like, Champagne being popped, it would feel a bit more real.

Tomm Moore: I think just having the whole crew watch the nominations was fun and nerve-racking. Never been nominated for another Golden Globe myself, so it definitely feels surreal.

RS: We haven’t seen some of the crew since last year when the film finished up. Because of COVID we haven’t gotten to meet. So it was just nice to see familiar faces.

Since Wolfwalkers went up on Apple TV+, what has the feedback and reaction been like, particularly from kids and families?

RS: Yeah, loads of kids pretending to be wolves and howling and running around on all fours in their sitting rooms and stuff. And what’s lovely is that it seems to be catering to such a wide range of ages. All the way up to teenage kids are loving it. I was wondering what the youngest would be, and I read a tweet yesterday from someone who said their 2-year-old loved it.

TM: I have a 3-year-old granddaughter who’s quite sensitive, and she’s Frozen mad. She just loves Elsa and Anna. And the other day, she wandered into the office and asked, “Could [I] watch Robyn?” She calls every movie by the main character’s name. We watched it up to the running-with-the-wolves sequence. We kind of left it at that because she gets frightened easily.

It’s great that it has such all-ages appeal, because one of the things that impresses me so much about this movie is the historical specificity. You turn Oliver Cromwell into this Claude Frollo–style animated villain. It grapples with the evils of colonialism and has a strong anti-puritanical message. It’s about the loss of this beautiful pagan culture, and the forests being cleared out. Why did you choose such a specific historical setting to tell this folklore story?

RS: It seemed like the perfect setting for the story that we wanted to tell because there was such conflict around this time in Irish history. It was a time of huge environmental destruction. The Cromwellian forces were ordered to cut down so many forests because that’s where the rebels and the wolves were hiding out. There was a determined focus to make the wolves extinct. And then there was also this huge clash of cultures: You had this old Irish culture that was pagan, like you say, but also had a very strong matriarchal kind of emphasis. There were powerful women leaders, and there was a connection to nature, and there was more of a symbiotic relationship with living. And then this puritanical force came in and replaced it. And it was very much patriarchal. It was very much dominion over nature. And it was very much about taming the wildness, inside as well as outside.

TM: It was also the time period where the biggest change happened in Irish history that we still have echoes of today. I think the whole world is waking up to the fact that we’ve all suffered from that colonial mindset for so long. I think it speaks to a lot of modern trauma that we still carry from that time period and that we need to move on from, given the crisis in the climate and the biosphere at the moment. That whole way of looking at nature as something to be dominated really has to change. It’s become urgent.

RS: And with regards to Oliver Cromwell — he’s, like, the villain of Irish history. He’s universally hated among Irish people. He’s the guy who canceled Christmas and everything.

The imagery at the end of Wolfwalkers can be read as fairy tale–ish; they’re in this flower-strewn carriage drawn by a white horse. But there’s also a secondary reading — and I haven’t seen anything about this, so tell me if I’m totally off the mark — are they supposed to be Irish Travellers?

TM: There was a bit of a feel of that. And definitely, we thought originally that Mebh’s accent and Moll’s accent would be a bit like a Traveller’s accent. Then we thought that was the period that the Travellers were kind of created. My family, the Moores, and the other family, the O’Dowds, were removed from their land by Oliver Cromwell, over to Connaught, over to the west. The Moores ended up settling, but the O’Dowds became Travellers. So that was a time period where a lot of the Irish Travellers started, or some of the Traveller families started. So it was kind of a little echo to that, with the wagon and everything, but not being so specific. Because the Irish Travellers have become a culture onto themselves and will have their own stories to tell about themselves. So it’s just a bit of a nod.

RS: I’ve read a couple of books about the Travellers, and — less so I suppose lately, because of the influx of modern influence and technology — they were the keepers of so many old traditions. There was a great musical tradition among the Travellers, and they had their own language, the Cant language. And they used to tell lots of stories. And they used to have all the old crafts and everything. So it was kind of a nod to this older way of living that was gradually being forced out by a newer society. One thing about the ending is it’s very bittersweet. They are uprooted from their home; they’re forced to travel off to somewhere where they won’t be persecuted. And ultimately, the wolves do go extinct in the 17th century, which we didn’t sour the ending by proclaiming. But there is definitely a kind of melancholy to the ending, in that they have to run away to survive.

You’ve mentioned before that this is the ending of your Irish-folklore trilogy, the other two films being The Secret of Kells (2009) and Song of the Sea (2014). How did approaching Wolfwalkers as the third film in a trilogy inform how you made the film?

TM: We’ve been working together for 20 years now. Ross and myself sort of felt like, let’s come up with something that takes everything we’ve learned from the previous movies and pack it all into one last bite at the apple, in a way that would feel like we were free to go in different directions. Because there were themes and visual ideas and music ideas and story ideas and everything, tying through the previous two movies. So when we came up with it, we were thinking along the lines of this being the last one of this little triptych.

As trends in children’s animation move toward making movies look as un-stylized — and even photo-realistic — as possible, Wolfwalkers goes in the opposite direction, having a distinct aesthetic, embracing stylized flatness.

RS: Maybe in the big-budget movies, but there’s definitely lots of really great animated films that have come out consistently that have embraced their own styles and not been the typical realistic or pushing-toward-realism style. Like Rémi Chayé’s films, Sylvain Chomet’s films, great European films like that. Not even to talk about the Japanese ones that have come out that have really embraced a unique style.

TM: I think because we’re in the Anglosphere, and we’re a Western culture, we’re kind of a bridge. Ireland’s always been like that. So I think that’s how our movies have … they seem really out there and arty and different sitting beside mainstream U.S. studio fare. But I think they seem a little bit more accessible — a little bit less “foreign feeling” than a lot of other European movies — to American audiences. I think we just benefited from that middle ground. But I think for us as animators, the point of making an independent film is that we can offer something different than what the mainstream is. Because there’s a definite commercial value to fitting in. There’s a commercial value to parents feeling comforted that this looks like a Disney or a Pixar [film]. But if you come up with a style that’s your own, you will stand out, for better or worse.

RS: We did notice that Cartoon Saloon films tend to be shown in art-house cinemas, while in the mainstream cinemas, something that might be made in whatever the popular CG format is might make ten times the box office. We’re always up against that. The commercial pressure.

TM: We have been around long enough now that it feels like it’s kind of come back into fashion. The stuff that we’re doing might have seemed really weird 15 years ago because everyone was rushing toward CG. But now I’m seeing stuff like Spider-Verse. Big studios are starting to get kind of experimental. And I think audiences are a little bit tired of that super-realistic, uncanny-valley stuff, and they’re eager to see more illustrative or experimental visuals. I always say, “We wore the same pants for long enough that they came back into fashion.”

The Anglosphere angle is definitely a part of it, but I also think your storytelling is more accessible and easier to fall in love with, for children, than some of these other visually exciting works. Young kids aren’t watching The Triplets of Belleville.

TM: They were children’s films. So that was another thing that joined all these three [in the trilogy] together: that the ambition was 8- to 10-year-olds. That was our primary audience. And then the animation fans and adults as a secondary concern. I don’t know. Maybe the next movies we make will be more focused at different demographics.

One of my favorite things about the animation in Wolfwalkers is the visible pencil lines. They do so much for movement and expression. I love seeing those sketchy lines either kept in, or overlaid, or however you do it. It reminds me of The Aristocats — that cool, retro sketchbook style.

RS: With the actual pencil marks you can really see how the different artists would approach their animation, some cleaner, some rougher.

TM: You can see the artist’s hand. I watched Shaun the Sheep: Farmageddon the other day, and I love that because there’s just a tone. You can see the thumb prints on their faces, but it’s actually really touching. At first it’s goofy because it’s just little Plasticine characters, but you really buy into them. It’s amazing how it’s able to be both tactile and handmade, and also really engaging and believable at the same time. It leaves the rough edges in, and it’s part of the job. When you can see the craftsmanship of the animation, it definitely gives a different tone than when everything is all smoothed off and perfect.

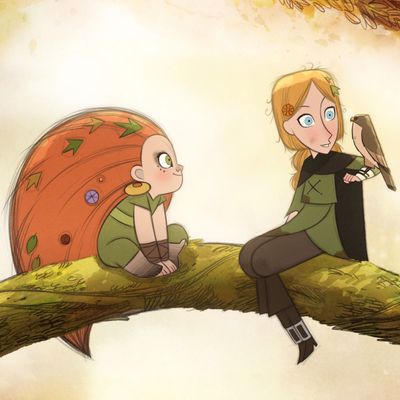

How involved were you in the character-design process? The designs are so wonderful, especially those of Mebh and Moll. Moll is just this giant, powerful, big hug of a person.

RS: She’s a big Earth mother. An Earth-mother goddess.

TM: She was probably one of the saddest casualties. In terms of design, Ross and I both come from a design background, and we did a lot of early concepts and designs ourselves, but we were also really surrounded by an amazing team. And a big thing for Ross and myself was that we were kind of tired of our own style. So we were delighted [to have] other artists like Federico Pirovano on the characters, and Maria Pareja on the backgrounds. They brought their own style to it. With Moll, we had designed her, and even in the trailer, everyone was kind of excited by her as a character. And the same thing happened a bit with Bill and Lord Protector. These adult characters were becoming so interesting that scenes that we’d storyboard with them — people were mad to animate. We had to cut things down. And I remember there was one scene in particular that even the voice actor, Maria Doyle Kennedy, had done a fantastic performance — of Moll saying good-bye to Mebh on the night that she has to leave. It was a really poignant moment. And we ended up trimming it. We really thought it was a great scene, and so many animators wanted to animate it, but ultimately, we had to serve the fact that it was going to be Robyn’s story first and foremost. So we kind of left Moll much more mysterious. But it’s been fun to see what a fan favorite she’s been.

She’s very much in line with the internet’s love of Steven Universe’s mom.

RS: Yeah, there is that, isn’t there?

TM: And Steven Universe is funny because we had this joint evolution with them — because we had Lisa Hannigan in Song of the Sea, and then she did a voice in Steven Universe. So I feel like some fans of Steven Universe discovered Song of the Sea backward from loving one or the other.

I want to ask about your decision to animate the wolves, distinct from the wolfwalkers, as less anthropomorphic. There is an alternate-reality Disney version of this movie where Robyn turns into a wolf at night and all the wolves sing her a song, or something like that. What was the thinking behind animating them to behave like a more literal wolf pack?

RS: We had to do that because one of the questions that Robyn asks is, “Are all of the others wolfwalkers, too?” So we had to really make the animals very much like animals. Otherwise, there might be all kinds of questions thrown in, like, “Are some of the wolves [wolfwalkers]? Do they have some kind of human personalities to them? How great is their intellect?” And all that. The closest that Tomm and I got to an argument was about Merlyn, because Merlyn is a wild animal. And I remember very early on, we had discussions about how much of a human expression or understanding Merlyn could have. Because he could go from being a little human birdie, and then he could also be a completely wild animal with no empathy at all. Even though there is fantasy in the story, we had to straddle that realism. There is supposed to be danger there. There’s supposed to be the fact that you can get shot by a crossbow and die.

TM: It also speaks to the speciesism argument that we wanted to make the movie about in the first place: An animal doesn’t have to be human to have value. That there is personhood and value in the experience of wild animals, and that is enough in itself that they should be respected. We didn’t want to make it that only the animals that were able to talk were valid.

RS: Anthropomorphism is quite dangerous, in that the animals that show a little bit more of a resemblance to human activity, we put greater value on their lives. Even the difference between, say, dogs and pigs — that we can see a little bit more of our own personality in a dog, so therefore a dog is of greater importance than a pig. All these weird little arguments that the human race has made for itself.

At what stage into Wolfwalkers’ development did Aurora get involved? What was the process in matching the music to the “Running With the Wolves” sequence?

TM: That was a sequence that Ross and I were already developing with Guillaume Lorin, the storyboarder, into being a tentpole moment. It wasn’t a big moment in the script. But when you put things up on reels and storyboards, you start to see the movie in a very raw form. It felt like we really needed to emphasize for Robyn that this is a change that there’s no going back from. And then we wanted to have a little moment almost of just joy, where Robyn realizes what life as a wolfwalker could be and how free she could be — so the audience could understand how hard it will be for her to try to fit back into society in that kind of Puritan world afterward. So that sequence we knew was important. I think we always thought that maybe Bruno Coulais and Kila, the musicians that we always work with, would come up with something really perfect for that. But I happened on the song by chance when I was going for a run at lunchtime. That was before Aurora was super well known. She agreed to be part of the movie. And as we were working on the movie, she started rising in her stardom and doing the voice in Frozen and everything. So, yeah, it was just good happenchance. Good algorithm suggesting a good song for me.