Like Harvey Weinstein before him, Scott Rudin has been called an “open secret” throughout the entertainment industry. For decades, the megaproducer — one of only 16 people to have won an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony — has held a reputation as one of the worst bosses ever to work in Hollywood. Still, the press, and the industry itself, has often presented his abusive behavior — throwing computers, insults, and tantrums at his assistants — as the idiosyncratic by-product of an eccentric man. Even after The Hollywood Reporter published a piece earlier this month going into greater detail, Hollywood and Broadway largely remained silent.

Meanwhile, the whisper network has become a chorus, with thinly veiled tweets and Instagram posts from former assistants lighting up social media. As detailed in a 2005 Wall Street Journal profile titled “Boss-zilla!,” Rudin, by his own estimation, burned through 119 assistants over five years — or, as one former assistant describes it, “an absurd revolving door of disposable, interchangeable, bright young people whose purpose is to be the target and outlet for his anger.”

We spoke with 33 former assistants and interns of Scott Rudin Productions who worked for him from 1994 to 2020. While the date and length of their time there varies — from three days to three years — all shared memories of a workplace culture predicated on bullying and physical intimidation. The portrait of Rudin that emerges from their stories is remarkably consistent: constant verbal berating, sleep deprivation, and an ambient, paralytic fear dedicated to fulfilling the most mundane tasks, like ordering food or binding scripts. Many spoke on the condition of anonymity, citing NDAs, vindictiveness, and the influence he still wields. In response to the allegations listed below, Rudin released the following statement through a spokesperson:

“Scott has acknowledged and apologized for the troubling office interactions that he has had with colleagues over the years, and has announced that he is stepping back from his professional work, so that he can do the proper work to address these issues. That said, the ‘stories’ you have cited specifically herein are in most cases extreme exaggerations, frequently anonymous, second- and third-hand examples of urban legend.”

Since the publication of THR’s report, Rudin stated he was “stepping back from active participation” in the upcoming production of The Music Man, as well as films with A24, and would be seeking anger-management classes. Many insiders view the move as Rudin’s attempt to hedge his bets that he can, once again, weather the controversy. The reporting below, however, paints the aggregate image of Scott Rudin Productions as not merely a toxic workplace but one of psychological trauma. “There was a permanence to what he did,” one assistant said. “There’s something you carry with you in your life after that.”

The Rudin Files

I.

The Offer

For most interns and assistants, Rudin’s reputation as an intimidating boss was far from a secret when they accepted the job; it showed up in Google results that he would yell and throw things at his employees, and some applicants were warned by friends in the industry. But many wondered: Could he really be that bad? I’m pretty tough; I can handle it. Most believed that’s just how the entertainment business works — If I stick it out, I’ll be rewarded with career opportunities. It was worth rolling the dice.

“When I went in to interview for the job, the office culture was alluded to in a coy way: ‘I’m sure you’re familiar with this office’s reputation. We’re looking for people that are thick-skinned and can work in a high-stress environment.’” —Development intern and assistant, 2018

“They made it sound kind of nice. It was a $55,000 salary, which for assistants is actually good. You get this prestigious name, and it’ll look great on your résumé.” —Eileen Klomhaus, phones assistant, 2019

“The office attracts a cold-blooded, young-exec type who thinks, He’ll treat me differently. I know exactly how to make this culture work for me. Everyone is proven wrong eventually. Rudin lives to break people — with very few exceptions.” —Intern and phones assistant, 2015–16

II.

The Job

Over the years, the assistants who worked in Rudin’s office have been predominantly white, male, and under the age of 25. While job responsibilities often blurred, typically there were five kinds of assistants: the executive assistant (who handled schedule, travel, and logistics); the phones assistant (makes and tracks calls; known as the “hot seat” and commonly described as the worst job); the theater assistant (who dealt mainly with theater and event ticketing); the documents assistant (tasked with collecting, filing, and archiving everything from scripts to press clippings); and a personal assistant to Eli Bush, who, as one former employee put it, “is sort of Rudin’s Smithers.” Bush, along with Adam Rodner, was the rare Rudin assistant to rise into production after beginning as an intern. (According to a spokesperson, Bush left SRP last week.)

The schedule was grueling. “Every day, you’re getting in at 6 a.m. You’re probably working until eight, nine, ten at night. On the weekends, the assistants all take turns being on call for Scott, so you’re probably working at least one weekend a month,” one assistant said. “Even if you aren’t working in the office, you are probably still doing a lot of work from home to catch up on the sheer volume of what was expected of you.” Despite the scope of Scott Rudin Productions, it was a tiny operation. “I was shocked by how small the office was. I was picturing a 30- or 40-person office,” an assistant said. “There was a moment where it clicked: Well that’s why they’re all working 14-, 16-hour days — because they have an entire production company’s worth of work to do and it’s ten people.”

.

The Horror Stories You’re Told on Day One

Certain rumors of Rudin’s behavior were frequently shared among the assistants, particularly the newbies, as to become office lore. Really, it was to prepare them mentally for what might happen.

“There’s a girl who worked for him, and she passed out in the conference room in front of him. I think from pure exhaustion. He stepped over her, turned to an assistant, and said, ‘I’m going to go out, and I want her gone by the time I get back here.’ The other one is the dishes. This one’s pretty famous. Supposedly, he got off a call with a reporter about a story or review he didn’t like, and he goes into the kitchen. He takes all of the dishes out, and he starts slamming them on the floor. He breaks every dish in the kitchen. Then he silently walks out of the office and leaves.” — Documents assistants, 2017

.

8 Lessons Learned on Week One

According to five assistants and interns who worked there between 2001 to 2017.

1. “The first thing you’re told when you walk in the door: ‘Don’t look him in the eye.’ Because if he’s in a bad mood and he’s looking for somebody to yell at, he might pick you.”

2. “Never talk to Scott.”

3. “If you were in the kitchen/storage-space area, whether you were photocopying a script, washing the dishes, or restocking the fridge — if Scott came in, you were to try to exit immediately.”

4. “Don’t go into the storage closet if he’s in the office, because if he sees inside the closet, it could be dangerous for you. You have to make sure the door’s always closed when you’re in it. It was disorganized, and the thinking was he would be so upset by the disorganization something bad would happen. What would that be? I don’t know.”

5. “His phone cord is nine feet long. If you’re in his office, make sure you’re ten feet away, because then the phone won’t hit you when he throws it at you.”

6. “Don’t get up to pee or eat in front of him.”

7. “He has an enormous closet of snacks — giant Tupperware of M&M’s, Oreos, Cheerios. Don’t eat snacks when he notices things are low in the kitchen.”

8. “You’re not allowed to take the subway because you can’t lose cell reception at any point while you’re working for him. I would have to take these hourlong Ubers [paid for by the company].”

III.

Scott’s Neurotic Tendencies

As assistants described it, much of the job was taken up by an Olympic level of busywork geared toward not setting Rudin off — whether that meant getting his food order exactly right or making sure a document was handed to him in the right font. “There was a binder of all of Scott’s preferences and what needs to be ready for him in meetings. What not to do and why not to do it. And there are little stories in there. It’s all prepared by interns. I don’t think it’s an official document,” said a development intern from 2019. “There was a running joke that, even if you have done everything correctly, he will make up something he wants changed,” said one assistant. “One thing I’ve thought about for a while is: This is 100 percent not an efficient way to run an office. I think he indulges and enjoys the abuse.”

.

A few of his preferences:

According to four assistants who worked there between the early 2000s to 2017.

1. A cast list must be in alphabetical order by first name and not last name.

2. A photocopy must be perfectly centered.

3. A document must be in Garamond font size 12.

4. Every night he would get a black JanSport backpack delivered to him that would have materials he needed to read, and invariably he would not bring them back. There was a constant rotation of, “There needs to be this exact kind of black JanSport backpack at the ready for him.”

5. He did not like emailing or texting on the iPhone keyboard. There was a closet full of later-model BlackBerrys, the ones with the external keyboard. Because he would so often smash them.

6. I had put a little “Sign Here” sticker with an arrow right above a line where he needed to sign. (He was going through a big legal situation with Shuffle Along.) He was frustrated because he felt it should have been on the line instead of above it. He worked himself into a tizzy. He tried to pick up the chair he had been sitting in to throw it at me. He did not succeed in doing that. He ended up just shoving the chair at me.

7. I remember the routine and the intensity around making hole-punched scripts. They had these little brads. You’d have to hammer it, and it needed a top sheet, and it needed to be labeled on the spine. If there was a mistake, it didn’t slip by him. It had to fit into a mail crate, and a lot of times it couldn’t. It was the perfect illustration of what it felt like to work there: having to curate as many documents as possible and then being told he needs all of it in a really small box.

.

The Phone System

While the phones job was known as “the hot seat,” practically every assistant mentioned “rolling calls” — a description for the practice of calling and leaving messages with talent or other executives first thing in the morning. “When we do roll calls — which means Scott will run through a bunch of names — you feel like you’re going into fricking battle,” said one assistant. “He’ll start listing names at rapid fire.” Part of the reason for the early calls was so people in Hollywood would wake up to voice-mail messages from Rudin’s office. “It’s a phone game where you’re calling people, and if they answer, you hang up,” another assistant said. “The point is that everyone owes Scott a call, so Scott’s always in control,” explains an assistant. “Only he can decide to take the call or say he’s not available.”

Another tactic Rudin instructed the assistants to deploy was called “jamming”: When he owed someone a call, he would have assistants call the same number from two phones simultaneously so it would go directly to voice-mail. “Sometimes that person would call right back and say, ‘I don’t know how I missed the call. I’ve been waiting for a callback for months,’” recalled an assistant. “We would say, ‘Let me see if I have him.’ Then he would decline the call, and you would say, ‘Sorry, I don’t have him.’”

.

The Food System

There was a world of stress around Rudin’s food and drink preferences. Assistants said his requests were very particular. He liked his bagels perfectly burnt. Only a certain type of Oreo was stocked. “I will never look at M&M’s the same,” said one assistant. “His coffee would be a couple shots of espresso in a Venti Starbucks cup, full of ice with a bunch of heavy cream,” said another. “If the cream wasn’t this particular shade, it would infuriate him.” And you had to get it to him fast.

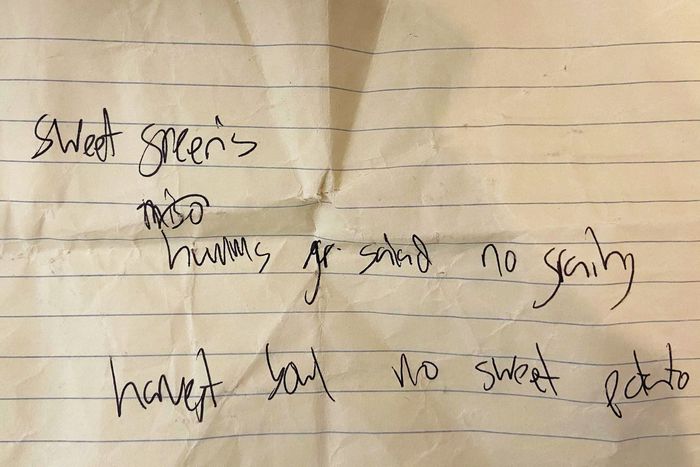

“One day, Scott barges in and is like, ‘I want food. Give me the hummus salad from Sweetgreen with no greens.’ I thought he said ‘no grains.’ So I confirm: ‘No grains?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, go get it.’ Ten minutes later, I’m getting calls from the assistants, and they’re like, ‘Where are you? Scott’s hungry.’ ‘Listen, the line is out the door. I’m going as fast as I can,’ I said. Five more minutes go by. They call me again: ‘Scott is pissed, he has to leave.’ They call again: ‘Where the hell are you? You’re going to be in huge trouble.’ I was like, “‘Shit, please give me a couple more minutes.’ I order the food, and I am sprinting back. When I run in, all the doors are open. They opened the doors so I could sprint into his office. I set it down, and he goes, ‘What the fuck is this? This isn’t my order. I asked for no greens.’ I was like, ‘Scott, I misheard you. I wrote it down.’ And he was like, ‘No, you didn’t write it down. You weren’t listening.’ I said, ‘Here’s my piece of paper.’ I pulled out a crumpled piece of paper. He was like, ‘Get out of my office.’ He threw the salad onto the tray that I was holding. I walk into the kitchen to put the salad away, and this other intern was like, ‘Holy shit. I heard all of that. Are you okay?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, this guy is literally crazy. I took his order down. I even confirmed it with him.’ I didn’t realize Scott was right behind me. He was so pissed I was talking about him, screamed at me again, called me ‘a fucking idiot’ one more time, and stormed out of the office.” —Justin Verbiest, development intern, 2019–20

“I Broke the Food System for a While”

“The Times Square Hale and Hearty Soups was a regular spot for Scott. You had to get him a menu every morning at 10:30 a.m. I ended up having an intern go to Hale and Hearty and buy every soup on the menu, and I would hide them throughout the office. Then I would bring in a soup menu, and he’d be like, ‘Well, it’s not going to be here for a half-hour,’ and I’d be like, ‘Scott, I got it.’ Then I would microwave the soup and have it there in five seconds like a fucking magician. He’d be like, ‘How did you do this?’ I’d be like, ‘I guessed which one you wanted.’ He was like, ‘Well, I didn’t want this one. I want another one.’ Then we’d play that game. He’d try to stump me, but he didn’t know if he opened a bookshelf he’d find some beef-stroganoff soup.” —Carl Neisser, phones assistant, 2016

IV.

Scott’s Classic Intimidation Tactics

Rudin’s behavior has often been depicted as the result of the amusing whims of an eccentric producer. But as described by his assistants, patterns begin to emerge. Many said they felt intimidated, manipulated, and threatened in their interactions with him, which created a tense environment where they were constantly on edge in anticipation of the next explosion. “When he walks in, it’s like a fear you feel through your arms,” one assistant said. “The impending doom pulses through your veins.” Rudin’s physicality was a key factor in this fear. “In addition to being a bully, Scott Rudin is a large man in all senses of the word. He’s a very intimidating presence,” said Sam Laskey, an intern and paid reader from 2008 to 2011. “When he would be angry at somebody, it was like a bull in a china shop: You’re trying to look at the desk, and you’re basically cowering in fear.”

He can be charming.

“What’s alarming about Scott Rudin is that he’s really fucking charming and funny. When he’s verbally abusing people, sometimes it’s zingers. You almost want to forgive him. Then it’ll make someone cry and it’ll ruin their life, and that’s when you realize it’s not funny.” —Development intern, 2019

And unpredictable.

“A hallmark of an abusive dynamic is not just that the perpetrator overtly mistreats you. It is also the ways in which they flatter and cajole you to let your guard down to believe, Oh, maybe this time things are different. Or the next time you actually have to do something for him, you were going to do it in a way to try and gain that validation again. It’s dangling the tiniest carrot in front of you so you don’t complain when he’s hitting you with the biggest stick.” —Evan Davis, assistant, 2012–13

“There was an assistant who Scott gave a very expensive pashmina to for her birthday. I was like, Oh, he must really like her. Then — I don’t know how long after this was — I came across her absolutely sobbing in the breakroom, being comforted by the office manager, another assistant. She was completely devastated by whatever he had said to her. And this was somebody he had bought a several-thousand-dollar pashmina for.” —Laskey

He can make you question your reality.

“He is a professional at gaslighting and manipulating to the point where he’s so confusing you start to question your own reality. He talks in shorthand, and he emails in shorthand. Sometimes it doesn’t make sense at all, and he will play off of that. When you don’t know what he’s talking about, it’ll send him over the edge.” —Documents assistant, 2019

And humiliate you.

“He had a hot-seat assistant who could take Scott’s shit like nobody else. He was great at his job, but Scott eventually starts looking for something about you that bothers him. For this particular assistant, it was that he ended every conversation and phone call with ‘Got it.’ It didn’t affect his productivity in any way, but Scott made it a problem — he made the person hang a huge sign over his desk that said ‘Don’t Say “Got it.”’ When the phrase slipped out one day, Scott began to lose it on this guy, so much so that he pulled him into the office kitchen behind a closed door. Scott normally has no problem tearing assistants a new asshole with everyone around. Then we all heard a glass shatter, and the assistant ran out and never came back. I went into the kitchen and cleaned up the pieces of a wineglass off the ground.” —Intern and phones assistant, 2015–16

“I saw the movie Whiplash and was blown away by how much the J.K. Simmons character nailed the psychological layer of it — identifying your spots of vulnerability, finding that nerve, and pushing at it.” —Junior creative executive, 2012–14

It can feel dangerous.

“He yelled at somebody in the office because they were wearing cologne and he didn’t like the smell of it. He came out of his office, took a full can of Dr Pepper, and threw it on the ground. It exploded. And he started screaming about the fact that his desk hadn’t been properly wiped down with a Clorox wipe. He wasn’t yelling at anybody in particular. He was just yelling because he was pissed off about this cologne. That was the first time that I was like, Oh my gosh, something dangerous could happen.” —Kiera Wilson, documents assistant, 2017

And make you freeze up.

“When he’s yelling at you, you’re in fight-or-flight mode. I would go into some other zone mentally where I’m like, I just need to get out of the situation. He calls me a piece of shit and I’ll just be like, ‘Yep, I am. I’m sorry. I’ll do better next time.’” —Development intern and assistant, 2018

“One day, I was bringing in a bunch of material for him, along with something he’d been gifted from a movie studio. So I physically had a stack of things in my arm. I couldn’t carry anything else. I walk in and he goes, ‘Pen and paper, pen and paper, pen and paper,’ and starts repeating it, getting excessively louder. Then he goes, ‘How are you going to remember what I want to throw out and what I want to keep if you don’t have a pen and paper?’ But he’s screaming. And he starts chucking pens at my head. I literally backtracked out of the conference room. You get so afraid, your brain gets cloudy and you’re operating off fear.” —Documents assistant, 2017

Sometimes he tries to make you emulate his anger.

“He would try to get me to yell at people on the phone. I remember once I was talking to the office, relaying some piece of information he didn’t like. And he was like, ‘You tell him this!’ I would say it in a more human way, and he would start screaming at me to say what he’d said: ‘Tell him he has the IQ of a plate or a baked potato,’ or ‘Tell him he’s brain-dead,’ trying to get me to channel his anger more.” —Assistant, 2002-03

.

Scott’s Insult Playbook

According to eight assistants and interns who worked there between 2008 and 2020.

One of the assistants kept a book of things Rudin had said to insult people. One infamous line was, “Is your brain the size of a lentil?” Another: “After this, you’re going to be flipping burgers at the Times Square McDonald’s.” He routinely insulted people’s intelligence and skills with terms like: “retarded,” “fucking idiot,” “fucking clod,” “illiterate,” “sloppy menace.” Once he emailed an assistant, “If I were you, I’d be embarrassed to show my face in a fucking remedial kindergarten classroom.” He often said, “Do you think what you did today would make your parents proud of you?” Another recalls: “When I was there, his line when he was mad at somebody was always, ‘What is the point of you?’ I hear it in my head constantly.”

The One-Word Command

Rudin was known for shouting out just one word, often repeatedly, to demand an item he wanted immediately — assistants cited LaCroix, coffee, cashews, sausage, and Diet Peach Tea Snapple as favorites during their time there. He often relayed his message by pressing a button from his office to shout into the main room where the assistants worked or sending a text message.

“Scott would yell ‘Snapple!’ and I’d have to run to the kitchen, grab a Diet Peach Snapple, and race to his office before he yelled again, which was like six seconds, usually. But sometimes he’d start yelling before pressing the conference button, which cut him off and made it difficult to figure out what he was saying. But you were supposed to react immediately, and you were not supposed to ask questions. There was one time where I didn’t understand what he said. So I said, ‘Could you repeat that?’ And he came out of his office and asked me in this mocking tone if I was deaf. At that point, you can’t really engage in an argument with him, because whatever you say, he’s just going to yell at you.” —Eileen Klomhaus, phones assistant, 2019

V.

The Physical Violence

Some of the most dramatic stories about Rudin involve his throwing items at assistants. What made him terrifying, though, was not just the violence but the sense that it could happen at any moment. “There was always the threat that he would physically harm you,” says Laskey. “That feeling is what makes him different.”

Multiple assistants described physical scenes happening behind closed doors:

“My co-worker and I were at the office super-late. Scott was there with his assistant producer — someone who used to be an executive assistant, whom he had adopted and brought on. He said or did something wrong, and Scott got pissed. He was like, ‘Fuck you. You’re useless. Get out.’ But he didn’t get out. All of a sudden, we hear this huge crash. Glass shatters. And immediately the air in the room changed. My shoulders were up by my ears. We heard this blood-curdling scream. Someone yelled, ‘You’re so fucking crazy. You’re insane, man.’ And then Scott goes off, screaming. He had taken his empty glass bowl of cashews — that he always had to have — and threw it. It hit the credenza and shattered on the wall. We had to go in and clean up all the broken glass and cashew bits. There was a dent in the cabinet when we went in there.” —Development intern and documents assistant, 2019

As another assistant from the late 2000s put it, it was chilling to hear the sound of an altercation from afar: “It was being somewhere in the back of the office, and hearing something crash in the front, and being too scared to get up and figure out what happened,” he said. “There’s something visceral about being in an environment that suddenly becomes violent. Over time, in talking about the experience, or reading about it, it becomes abstract, almost a joke. But it’s really jarring to hear a phone hit the wall, or to hear something shatter and have the natural emotion — to want to react or leave. But you have to act like it’s normal.”

When things did escalate to the point of violence, assistants described lasting effects. Kevin Graham-Caso, an executive assistant in 2008–09, began seeing a therapist specifically for PTSD after his time working for Rudin; he died of suicide last year. His identical-twin brother, David Graham-Caso, has stated that he believes Kevin’s mental-health issues were at least in part owed to his time working for Rudin, which three of Kevin’s friends confirmed. They cited one incident in particular in which Kevin was thrown out of Rudin’s car. “They’d be in communication about work, going from one location to the other, and then a little thing would piss Scott off and he’d be like, ‘Get out,’” said his friend Klodiana Alia. “But that time was memorable because Kevin said the car was still moving when he was thrown out. Kevin was humiliated and hurt. It was devastating.”

Another assistant recalled what happened when his colleague forgot to deliver a message to Rudin from the head of a studio. “That’s not good, right? The reaction that happened afterwards, I had never seen anything like it,” he said. “He picks up one of those big iMac computers, the see-through ones, and starts chucking them, one by one, across the room at the assistants. Not at a wall; at the assistants. We were all dodging them. At which point he fires everybody.”

“There was a permanence to what he did,” he continued. “There’s something you carry with you in your life after that, a distrust of people, maybe. When you know what a person will really treat another person like, and you see it … I don’t know, it changed me.”

VI.

Whom Scott Likes (and Especially Doesn’t Like)

Multiple people cited Rudin’s perceived tendency to favor white men over the people of color and women in the office — of which there were few.

“I had a fairly decent relationship with him. I’m gay, and I think he took a liking to me in part for that reason. He liked to mentor me. I felt I received unfairly better treatment than a lot of the women in particular in the office. I bore more witness to other people being abused. I saw him shove a printer off a desk towards someone. I was there when he pulled out a tray of glasses in the kitchen that shattered all around someone on the kitchen floor. But I was not the subject of that stuff.” —Assistant, 2015–16

“When I started my job, everyone sort of laughed at me in the office, and I would ask why. They’d say, ‘Of course he takes to you, this well-groomed, well-dressed, nice white Jewish boy.’ I think it’s because he sees the potential for us to be cruel in ways that other people can’t.” —Intern and executive assistant, 2020

“One of the first things any of the other interns told me was that it would be way easier for me because I was a pretty gay person and not a woman, and especially not a woman of color. He would have me do all of the runs; I would take things to his house so he could read them. That was an opportunity that was given to me because I was pretty; he could trust me. The Black women, especially, he would never trust. He doesn’t invest in them. My jaw would drop every time some poor girl got in his viewfinder. The way he was cutting and cruel to me was awful, but it was funny, because he was like, “Ha-ha-ha, whatever, you’re catty.” It was so much worse when it was targeted at a 21-year-old girl.” —Development intern, 2019

“I had to go to the front and get everyone’s coffee order. Scott came out, and he was yelling at this intern — a queer woman — about how his report wasn’t ready. He stops for a second and sees me, smiles, and he goes, “Hi. Nice to meet you.” And he was so friendly and warm. Then literally went back to screaming at this poor girl. It was that moment where I realized he seems to fetishize younger gay men and we get a little more respect from him.” —Development intern, 2019–20

“I definitely felt there was a favoritism towards the male interns and by the way, thank God, because that saved me.” —Intern, 2013

“Every time I submitted a document for review, he would say that my work was not as good as the man who worked in the position before me. So one time I had the man who was in the position before me do my job, because I was getting a little desperate and I didn’t know what I was doing wrong. I still got a response that said, ‘This isn’t as good as the man who had the job before you does it.’” —Amanda Pasquini, theater assistant, 2017

“The people who end up lasting longer with him are people who share some sort of adversarial spirit and lock horns with him. I didn’t take his fighting or insults as a game to be played.” —Junior creative executive, 2012–14

“I remain horrified that he liked me; I try to not think about that too hard and what that means for me and my personality.” —Intern, 2008–09

VII.

Celebrity Appearances

Famous people regularly cycled through the office to do business with Rudin. As some assistants tell it, it’s hard to imagine anyone walking into that space and not sensing that something was wrong — in part because Rudin often did not attempt to hide his temper in front of talent. “There’s an overwhelming energy of stress and dread that hangs over that room,” said one. “I do think celebrities who come in are aware of how it is and choose to turn a blind eye because this is a huge megaproducer who is going to get your project made.” Others felt that Rudin “flipped a switch,” putting on a different face when talent was in the office.

“One time, he was literally chewing us out. And then his executive assistant was like, ‘Timothée Chalamet’s coming up the elevator.’ As soon as the door opens, he literally turns from berating us and is like, ‘Buddy! How have you been?’”—Documents assistant, 2018–19

“On the first day I started as an intern, Chris Rock had come out of a story meeting on what was going to be Top Five. He walked past the front bullpen of the office and joked to all the assistants and the interns, ‘It’s okay. You can relax. I know he beats the shit out of you all day.’” —Junior creative executive, 2012–14

“He’s not above screaming at a celebrity if they rub him the wrong way; he’ll send a vicious email to someone who he thinks has crossed him and say he’s going to make sure they can never work again. But there is a difference between how he treats his underlings and how he treats talent. One of the hardest things as an assistant was you’d see these people waiting to meet with him, and they might overhear some of that abuse. There’s no way they didn’t — it’s open to the rest of the office — and they keep coming back.” —Assistant, 2015–16

VIII.

4 Firing Stories

Whether they were “soft firings,” where the assistant quickly came back to work after Rudin’s temper died down, or firings where they never returned, the producer fired people constantly. This was often the result of perceived slights or minor mistakes. As one assistant put it, “When you’re operating in a workplace where the employee who has the most institutional knowledge has been there for 30 days, it’s impossible to do your job correctly.” The only institutional knowledge that did exist was the fact that Rudin constantly fired people. “When I left, I left a 10- or 15-page document called ‘How Not to Get Fired by Scott Rudin,’” said an assistant who worked there in the 1990s.

“Maybe you’ll get in a car crash.”

“Rudin was working on what was at the time the Untitled Aziz Ansari Project, and Aziz Ansari came by the office. Scott had been mad at me previously in the day because I had not properly wiped down his table. And then I started to wipe down his table while he was at it, because he made it sound like that’s what he wanted. He completely lost his mind on me. It was one of those days where he was in a really bad way. He was screaming at people left and right for every single thing. As he was leaving, someone said, ‘Have a good weekend, Scott.’ And he turned to the room and said, ‘No, none of you get to have a good weekend after this week.’ Then he looked at me and said, ‘You live in Westchester, right?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He was like, ‘Well, it’s gonna snow this weekend. And I bet you drive, so maybe you’ll get in a car crash.’ And like, literally, I was looking at Aziz Ansari as he said it. That weekend, the office manager called me, and she was like, ‘I don’t know if Scott wants you to be there on Monday.’ And I was like, ‘Great, I’m not going to be there on Monday or ever again.’” —Documents assistant, 2017

“You’re done, you’re finished. I don’t ever want to see you again.”

“I had been soft fired four or five times before it stuck. He snaps at you and says something like, ‘You’re done, you’re finished. I don’t ever want to see you again.’ And the expectation is you go home or you wait at the Starbucks downstairs, and either an assistant will flag you back in later that day, or the next morning you’ll come in as though nothing has happened. I got soft fired because I had to make him a DVD of clips of actors for the Broadway production of The Crucible. He was mad that the volumes were at different levels based on the initial sources. He was upset he would have to use this remote to turn up and down the volume accordingly.” —Junior creative executive, 2012–14

“What the fuck?”

“I saw a guy get fired before 7 a.m. on his first day. I go, ‘So here’s the deal: If the phones ring, you answer, and you say “Scott Rudin’s office.” The phone rings at probably 6:45, and he picks it up and says ‘Scott Rubin’s office.’ And it’s Scott. You just hear through the phone so many expletives: ‘What the fuck?! “Scott Rubin”? You’re fired! Get the fuck outta here!’ He packed his stuff up, and he was gone by like 6:58.” —Assistant, 1990s

“‘My bad?’ What is this, fucking high school?”

“I was let go because I didn’t know about a meeting, and because of that, I didn’t have a script printed. Scott confronted me and said, ‘Where is this?’ He kept yelling and yelling, and eventually I looked at him and I said, ‘Scott, I don’t know what to tell you. It’s my bad. I didn’t know about the meeting. I can print it for you now. Do you want me to or not?’ He looked at me and said, ‘My bad? What is this, fucking high school?’ He was like, ‘You’re done here,’ and then he started kicking and throwing things. He went into the kitchen at one point, and we just heard stuff breaking. You don’t see him, but you imagine this tiny dinosaur-arms toy being let out of control. On his way out, he kicked the wall and slammed the door. I just started laughing, and I was like, Okay, I guess I’m done.” —Documents assistant

.

One Quitting Story That Resulted in a 45-Minute Tirade

“I had a good relationship with Scott until the bitter end. I eventually quit because it got to be too much of an emotional toll. I was the first one in that day, and he said, ‘Hey, good morning. All right, what the fuck is going on with this list of calls? God, you haven’t set a single one of them. You’re really fucking it up.’ I looked at him and I was like, ‘I’m not here for this.’ And he was like, ‘What do you mean you’re not here for this?’ I started going into my rehearsed speech of ‘Thank you so much for this opportunity. I’ve learned so much from you,’ and he goes, ‘I don’t care. You’re so stubborn and selfish and stupid, and no one will ever want to work with you in this industry. You’re fucking up something that could have been really good for you.’ I said, ‘I know.’ He went into me for 45 minutes, trying to break me down.

“I was telling myself, Dude, don’t cry, don’t cry, don’t cry, don’t cry. I teared up at one point. I was just staring at him — his empty eyes, his empty face. Eventually he turned back to his computer and was like, ‘I’m done with you.’ I went to walk out, and he turned and said, ‘You’re really doing this, aren’t you?’ Like ‘You’re really, really, really fucking this up, aren’t you?’ I said, ‘I’m not going to be verbally abused by you on a daily basis.’ He said, ‘This isn’t verbal abuse. This is me trying to push you to be better, to be tougher, to be stronger.’ I said, ‘I am tough. I am strong. I am better. I’m out.’ —Max Hoffman, intern and executive assistant, 2020

IX.

The Mental-Health Toll

Former assistants described the symptoms they experienced working for Rudin in disturbingly similar ways. Some of them manifested in physical ways while they worked there. Others came out through years of therapy, or were triggered unexpectedly, and resulted in a dramatic change in self-worth in future jobs and relationships. Much of the suffering was compounded by how isolating it felt to work for Rudin. “You’re basically chained to email all day and night,” said one assistant. “So you’re going to sleep reading these crazed, invective-filled messages from him and waking up to them. There is something clever in a diabolical way about how he works. We were all ambitious young people, and there’s a part of you that’s like, I’m clearly not keeping up with him. There’s something wrong with me.” Here are 15 ways assistants and interns, working between 2008 to 2020, described the personal damage:

1. I had my first panic attack in a toilet.

2. My skin broke out constantly because of the stress, which was not a regular occurrence for me before or after.

3. I had terrible diarrhea because my stomach was constantly in knots.

4. I struggled to eat due to nerves. I lost weight.

5. I gained weight.

6. I lost hair.

7. I was so afraid of going to work I would wake up every morning with hives all over my body. I would take Benadryl all day to keep the hives under control, but then I’d have to chug Red Bull to keep myself from getting drowsy.

8. I had a bad kidney infection because I could not pee. It’s the worst feeling in the world. I talked to my aunt, who’s a nurse practitioner, and I have stress-induced bladder spasms. Now I get to go to a physical therapist and learn how to control it.

9. I had nightmares about it for a long time, and it affected my sleep. I was like, Wow, I haven’t slept for this whole year.

10. I got stress-induced pancreatitis. It’s funny seeing photos of us when we worked there because we’ve all had such glow-ups.

11. It permanently fucked my nerves.

12. I always said, “The day he makes me cry is the day I’m done,” because he had never made me cry and always made everyone else cry. Not that I think that I’m any stronger than the others — everyone who works for him is strong. But the day I eventually I cried, I was like, Fuck, he got to me.

13. We all knew Scott was a horrible guy, but we had Stockholm syndrome. All the interns got to go to one of the dress rehearsals for West Side Story and we’re sitting in our seats and Scott waves to us and we all freak out. We’re all like, “Oh my God, hey Scott!” Like so excitedly waving. And you know he didn’t give a shit about any of us. We all wanted acknowledgment from him even though he was so terrible to us.

14. I quit after a bunch of soft firings, and I came back two weeks later to help train my replacement. Everybody looked at me like I was a different human. They were like, “The light is back in your eyes. You look like you’ve gained ten pounds back on your face.” It’s slow in how it gets you, but once you’ve been there a full year, you’re forever different. The environment adds up to lasting, serious damage.

15. The only way to succeed in it is to completely dedicate yourself to it fully, and that often means losing your ability to see the situation for what it is. You start to lose your own humanity.

.

The Aftershocks

“A couple months into the job I had after Rudin, at a television network where I still work, my boss called me into his office, and I ran in with a little notepad. He asked me to do something, and I said, “Yeah, okay,” and I ran out of the office. He called me back in and said, “I need to ask you something. Why are you like a rescue puppy? You don’t need to run into my office.” He was trying to say, “Am I being rude to you? Do you feel nervous?” —Kiera Wilson, documents assistant, 2017

X.

A Scott Rudin Origin Story

Chellie Campbell worked as an assistant to Rudin and his boss at the time, television and film producer Edgar Scherick, from 1982 to 1984 in Los Angeles. Having worked with Rudin when he was in his early 20s, Campbell saw a different side of the producer than assistants in later decades. While Rudin was demanding and would yell at Campbell, Scherick’s constant angry outbursts were much worse, she said. She felt that Scherick’s actions signaled to Rudin that this type of behavior was acceptable. Campbell, who is currently 71 and a “financial stress reduction” coach, left the entertainment industry after working for Rudin and Scherick. She recalled the first job interview she had after leaving: “They said, ‘Well, the main thing we want to know is if you can work with difficult people.’ I burst out laughing. I said, ‘Let me tell you some stories.’”

“He would have been 23, 24, and had just come from New York, where he had gotten a very early start at age 16. He was very charming during the job interview. Very nice to me. I was about ten years older than him. I remember him asking if it bothered me that I was older than him. I said, “No, you’re a producer. I’m not. I’m happy to learn what you know.” I worked for him for about nine months and then I moved up to working for Edgar. I found much more anger and eruption from Edgar. He was so volatile. One time he jumped up on my desk, screaming at the office runner who did errands all the time. I had never seen people behave like that. And that was happening all the time. Scott, it seems to me, kind of got permission. These people are not alone in the motion-picture industry of being screamers.”

XI.

Normalizing Scott

.

In the Office

Many assistants described a sense of solidarity, where they would try to shield one another from Rudin’s outbursts. “The film The Assistant, by Kitty Green, felt like it was plucked whole cloth from my brain,” Davis said. “There’s that moment where the other two assistants helped Julia Garner write an apology email to him — the other assistants did that for me. I quote-unquote ‘fucked something up’ in the mind of Scott, he unloaded on me, and three of the other assistants basically workshopped an apology email for me to write. We all did that for each other in various ways.” Others noted how quickly Rudin’s behavior became normalized in the office. One intern recalled a time an assistant brought Rudin the wrong medication — it was either Advil or Tylenol — “so he threw it at her. She ducked, and it did not hit her, but he was aiming for her head. Because it was so ritualized, people reacted like, ‘Well, why didn’t you bring in the one he asked for?’ Which is not how human beings should react.” Getting screamed at by Rudin was so banal in the office that, after one’s assistant’s first experience with it, “everyone was like, ‘That’s good, you got it out of the way — your first Scott tantrum.’ It was weird to me that the attitude was, ‘At least you got it out of the way.’ That it was just kind of a hazing thing.”

According to multiple former employees, Eli Bush — who started as an intern and until recently served as a top executive at SRP (with producer credits on films like Lady Bird, Annihilation, and Uncut Gems) — was one of the few people to quickly climb the ranks and stay there. “Eli is an amazing survivalist. Nobody does that job with that much proximity to that ruthlessness without a sense of cynicism. When Scott would leave the office, Eli was one of us — air quotes ‘one of us’ — and then when Scott was back, you’re just on your own. He really fucked over a lot of assistants that just were kind of in his way. He’s in this really ugly machine, and I can’t really empathize with a person who stays there for that long,” said Neisser. “It’s one thing if you’re learning the ropes, and you eventually come to understand, in your mid-20s, Oh, this is bad. I should go. It’s another thing if you really make this your brand.” As another former assistant put it, “It’s like bowling: His job’s to put the pins back up so Scott can go in and knock them back down.” (Through a spokesperson, Bush declined to comment.)

.

In the Industry

Assistants had various theories as to why Rudin’s behavior had been accepted for so long: the normalization of abuse within the industry; the power Rudin wields in both Hollywood and the media, where he’s a major and regular advertiser; the fact that many are bound by NDAs. But many noted that working for Rudin was viewed as impressive precisely because of his reputation as a terrible boss. A job at SRP was often described as a rite of passage, even as it had the effect of driving many people out of the industry. “There’s the idea that it looks good on a résumé,” said one assistant who worked there in 2018. “It catches eyes, and that is still true. Every interview I’ve done since then, people bring it up. They’re all aware of the reputation of that place and what it means. There’s a little bit of like, ‘Well, you survived that.’”

“I’m embarrassed about the extent to which I wore this whole experience as a badge of honor for years. At parties or in classes, or when I was at a meeting in L.A., that was a great point of conversation: ‘I survived Scott Rudin’s office.’ ‘Oh, wow. What was that like?’ I bragged about it rather than stopping to reflect and say, ‘No, this is awful. This is not an environment anybody should be asked to work in.’” —Laskey

“There’s an implied social contract. People think if you’ve worked for him long enough, you can write your own ticket in the industry. What’s challenging is that Scott is so self-sufficient in terms of how he develops, you don’t actually learn a lot about the day-to-day mechanics of producing. You really just learn how to work for him.” —Junior creative executive, 2012–14

“I interviewed to be a personal assistant to an Oscar-nominated director after I left SRP. The interview was not going well, but when I mentioned I was actively looking for a job with a different working culture than Rudin’s, I was shown the door. That’s my experience in the industry in a nutshell.” —Intern and phones assistant, 2015–16

“I felt resentful of people in Hollywood. Greta Gerwig has done many movies with him. But she’s also a champion of people. Beanie Feldstein — how progressive are you? I was excited about being a part of the industry, and seeing how bad behavior is okayed because it fulfills other people’s motivations and desires was disillusioning. It’s the culture of complacency; that it’s okay — as long as the movie gets made, or as long as we win the award, or the recognition comes in, it doesn’t matter how we got there.” —Documents assistant, 2017

“I knew someone who worked for Vulture a few years ago, and at the height of Me Too, they asked if I could find people willing to talk about Rudin. It never got that far because the pitch was apparently met with silence. Everyone in the entire industry, even you and I, are culpable to abuse in some way or another.” —Intern and phones assistant, 2015–16

“The Catch-22 of working there is I also have judged assistants in my own career for lacking attention to detail. There’s a weird way you internalize it. Are we going to decide this behavior is archaic? I think we have a generation of filmmakers and executives and actors who are all deciding that maybe our legacy is that we don’t want to punch down just because we were punched.” —Intern and development assistant, late 2000s

XII.

Breaking Free of Scott

I tried very hard to never become Scott. I started as an assistant in 1994 at 22. I got promoted to story editor. I was director of development at age 24, and he offered me the VP job. I had to make a choice: Do I want to keep going down this path and become Scott? Or do I want to get the hell out of here? I quit and I gave five weeks notice. On my last day, I spent hours locked in his office. He was trying to turn the thumbscrews to get me to sign an NDA. And I said, “Man, I’ve already made my choice not to be in this world with you. I am not signing an NDA.” I was literally the last employee to leave that office without signing one. He started with the whole “You’re an ant, you’re a nothing. You’re a glob of spit. I will crush you. You’ll never work in this town again.” You’re 24, and you’re like, Oh, I have just pissed off a titan. And there is nothing I can do about this.

I ran into Scott one other time after that. I was Rollerblading through Central Park. I did the only thing I could, which was blade right over to him to show him I was no longer scared. And you know what happened? He was charming as hell because I was no longer someone he had any power over. The power dynamic was no longer there. It was sickening to see him have absolutely no guts outside of that office space.

Suddenly as an adult, I’m looking at it and I’m like, Who the fuck does this guy think he is? The 48-year-old me is pissed as fuck about how he treated 22-year-old me. That was 25 years ago, and every single person who has worked there since has had to shut up about their stories. The more I talk about Scott and remember everything, the more I want you to put my middle name in the piece. I want it in the biggest goddamn font you can find. I want him to know who’s saying this, because I have the ability to say it. I’m saying this for all my friends who can’t, who are tied to these NDAs, who are worried about getting sued by Scott. I hope once the NDAs are released, every single person shares every horror story that that man has ever inflicted on them.