In an anniversary that screams “Wanna feel old?,” last week marked 20 years since the release of Spy Kids, Robert Rodriguez’s candy-colored YA adventure film that made a generation of children wish Antonio Banderas was their dad. The movie was groundbreaking for its portrayal of a Latinx secret-agent family — which Rodriguez had to convince the studio to include — and spawned a franchise that saw preteen siblings Carmen and Juni Cortez fight off a series of escalating maniacal enemies and nightmare-inducing baddies.

The series’ first antagonist was Tony Shalhoub’s Alexander Minion, a former agent who uses a children’s show hosted by the eccentric Fegan Floop (Alan Cumming) as a front for his plan to mutate all spies into monsters so grotesque that I’m surprised I’m not still traumatized. On top of that, he also wants to build an army of intelligent-robot kids. Writing it out like that makes Spy Kids sound totally unhinged and … well, it is. But Rodriguez’s fantastical dreamscape hearkens back to an era when four-quadrant popcorn movies could just be weird without having to explain themselves. Artificial thumb bodyguards? Sure, why not! The beauty of Spy Kids is that it knows no bounds.

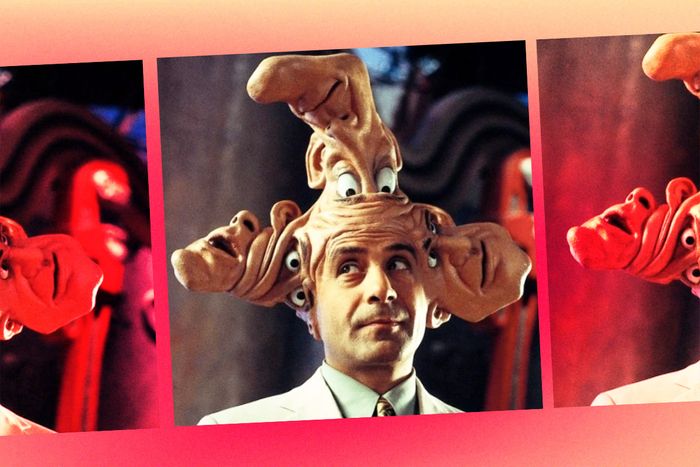

In a movie where its cast has to compete with the depths of Rodriguez’s wild imagination, Shalhoub remains an easy standout. Minion’s arc in the first Spy Kids culminates in him growing three extra heads thanks to his own invention, but Shalhoub plays everything so hilariously straight-faced that it only enhances the chaos around him. The beloved actor has an enviable résumé, ranging from cult films (Galaxy Quest, Big Night) to Emmy-winning performances (Monk, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel), yet Spy Kids rises to the top as a role he still treasures, as evidenced by his endearing eagerness to show off the bust of his character that he keeps at home. “I’m trying to get it in the right light,” he says, as he tries to take a picture. “It’s pretty cool. It weighs a ton, by the way, just so you know when you see it.” In light of the film’s milestone, Vulture called up Shalhoub to talk about his memories of playing a multi-limbed evil scientist.

Where were you in your life and career when this role came about?

I had done a series in the ’90s, Wings. I think this had to have been before I started Monk, which probably came right after this. But I was living in L.A. We had two daughters — they were, at this time, 11 and 6 — and [Spy Kids] seemed like a great opportunity to do a kids’ movie, and I was a big fan of Robert Rodriguez. That’s where I was in the continuum.

How was Alexander Minion first described to you?

I had read the script and then I was invited by Robert and Elizabeth [Avellán], his wife who was producing, to come out to Austin. I think, at that point, they may have even had some of the sets built. He wanted to go through not exactly a storyboard, but just drawings of the different creatures and things that were going to be animated, just to give me an idea of the world of the whole thing. He originally described Minion as a nerdy scientist who turns out to be quite diabolical.

Minion has this interesting arc: You’re initially led to believe he’s just the villain’s sidekick and then he’s revealed to be the mastermind behind the whole plan. But then, in the sequels, he’s actually reformed and helps the Cortez family. I liked the idea that anyone can have a shot at redemption.

I liked that too. I mean, I certainly didn’t know that was coming. I don’t really remember us having a conversation about the sequel when we were doing the original, but certainly in the character of Floop, Alan Cumming’s character, there was that element of: We think it’s the villain, but he turns out to have an empathetic side. So certainly that was in the narrative. I just love that idea that [Rodriguez] was illustrating, for his own children and kids in general, that it’s okay; your shortcomings don’t necessarily define you. The things that you maybe don’t like about yourself, or possibly have shame about in yourself, you can evolve past. Change is not only possible but inevitable. I liked the message that was being put out there for my own kids, too.

I’m curious to know what Robert Rodriguez was like as a director. He said that he wanted the film to feel like it was written and directed by a child. Do you think that childlike energy was also reflected on set?

Absolutely. He’s much more than a director. He’s everything: He’s a one-man army; he’s the writer; he operates the camera; he edits the film; he does the music. He does everything. He explained to me, in our first meeting, that when he was a kid — even before he started filming things — he was drawing and making figures and creating characters on paper. He has so retained that kind of childlike quality of wonder, creativity, and fearlessness. Kids just go into things full bore, without really contemplating the consequences, and he does that. I did see him as this very larger-than-life talented kid all through the production. It was delightful.

It was quite a personal film for Robert as well. He incorporated elements of his life and dreams into the story. Did he ever talk to you about that?

A lot of the work he had done prior to that was more geared toward adults. He had at least three or four kids, and what he did talk about was that he wanted to do something for them: an entertaining but teachable moment, something to inspire them. [He wanted to] tell a story that would make it okay for them to make mistakes and rise above them.

The concepts in this film are so wild and eccentric, like the thumb henchmen and the Fooglies. When you were seeing these creatures, did you ever have a moment where you were like, What am I getting myself into? Or did you just fully trust Robert’s vision?

No, I didn’t question it for a minute. As I said, my kids were young, and so, as a parent of young children, your whole mind-set is kind of moving at least 50 percent in that direction anyway. We’re reading to them when they’re little, we’re playing with them — we’re kind of in that world anyway. So all of these images that Robert was throwing at me, I was kind of trying to see it all through my kids’ eyes and how much they would get excited and inspired by it. I didn’t question that at all. I embraced it fully.

What did your kids think of the film?

They were crazy for it. In fact, we went to the theater for the premiere with both of them, and the first thing my older daughter said to me at the time was that she wanted to be a spy. She had decided that that’s what she was going to do with her life.

After Spy Kids, there was a whole wave of adventure movies geared toward children.

It was groundbreaking in a lot of ways, because the family was from the Latino community. I don’t think there was anything ever like this before. So it had that whole component going for it, too. It was comedic. It was a little creepy in places. I think it had a bit of a darker side. It just checked a lot of boxes.

It also cultivated this legacy as being a major part of millennial and Gen-Z childhoods, at least for me — I watched it a dozen times when I was a kid.

I’m happy to hear that it really did land in the way [Robert] intended, or even beyond the way he intended. I know that there are a lot of fans of the film, because sometimes when I’m recognized, that’s the thing that people talk about, especially people of your generation. It’s good to know that it was not just a job but that it’s had some life.

Is Minion one of the roles you get recognized most for?

I don’t know that I would get recognized most for it. It just depends on the age of the person, mostly. And I get recognized for a number of different [things] — Men in Black, Galaxy Quest, Monk, of course. But I’m really very proud to have been a part of the Spy Kids movies.

Jumping back to the movie, Minion falls victim to his mutating machine and grows extra heads and limbs. Was that effect all practical?

Oh, yes. They built this gel mold of my face contorted. [Robert] did all of that, by the way — that was all his work. He designed that whole thing. In fact, I can send you a picture of it. It’s amazing. He made a clay mold of these three heads — well, four, because my face is included — and then he bronzed it and gave it to me as a gift. It’s really incredible. I’ve kept it all this time. It stands about a foot tall, and it’s about a foot wide, and it’s exactly what I wore. I wore this enormous thing on my head. It was lightweight, but it was big.

Was it difficult to wear?

It was not heavy, but it was somewhat precarious. I can’t remember exactly how they [did it]; maybe they stapled it to my skull. But no, it was not terrible. I’ve had many worse things I’ve had to put on my face and my head.

I really loved the dynamic between you and Alan Cumming. What do you remember about working with him?

Alan!? Oh my God, it was thrilling. Alan and I both came up in the theater. He’s just a massive talent: singer, dancer, a jack-of-all-trades. I had never worked with him before — or really any of those people. Carla Gugino became a good friend, and I got a chance to work with Antonio Banderas, whom I always loved. The whole thing was just full of great people.

How do you see Spy Kids within your career?

The projects you work on, they’re kind of like your kids or your pets: They’re different, but you love them, and you’re appreciative of them for different reasons. Spy Kids came along at a really perfect time in my life. I’m not sure, had I been in a different place in my life, maybe I would have made the mistake of not doing it. But all of these elements came together at the right time, at the right moment. Like I said, I keep this bust of the three heads in my living room, so obviously it’s something that I value.