Truth or Dare is a snapshot of stardom in 1991, before fame was something that existed in people’s pockets. Pop documentaries have surged in the past decade, with many younger artists striving to make their own versions of Truth or Dare. Try as they might, Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, Billie Eilish, Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, Justin Bieber, the Jonas Brothers, Ed Sheeran, Demi Lovato, Ariana Grande, Shawn Mendes, and Coldplay can’t quite replicate the novelty of early-’90s Madonna. (Time will tell whether Pink, Nicki Minaj, Rihanna, or Alicia Keys can do any better.)

Maybe that’s because Truth or Dare wasn’t initially designed to be so personal. What began as a traditional concert film ripened when director Alek Keshishian observed the seven dancers, two backup singers, and dozens of attendants in Madonna’s retinue. What came next was less a celebrity-branding ploy than an organic peek behind the Blond Ambition Tour’s curtain. Madonna funded the roughly $4 million project herself, according to producers Tim Clawson and Jay Roewe, but she and Keshishian created a new approach to storytelling, unburdened by any rule book.

“The movie isn’t pure cinema vérité,” explains Keshishian, who scripted Madonna’s pensive narration. “It’s kind of this odd hybrid.”

What’s most striking about Truth or Dare 30 years later is that, unlike the subjects in today’s pop docs, which tend to emphasize solitude and struggle, Madonna looked like she was having a ball. In the vein of the Old Hollywood luminaries she idolized, she adores being famous; she’s good at it — or at least she was, before becoming hyperdefensive over the past few years. Long before social media warped celebrities’ self-perceptions, Madonna understood the mechanics of fame in a way that some of her peers did not. “Even if the camera followed me around for my entire life, how can you ever really completely know me?” she told MTV’s Kurt Loder when asked about the film’s limitations.

At the time, mystique was thought to be fame’s ultimate fertilizer, and Madonna’s then-boyfriend Warren Beatty scoffed that she “doesn’t want to live off camera.” Beatty wasn’t wrong, though: Madonna was an exhibitionist before everyone became exhibitionists. She came across as a freewheeling den mother and a haughty taskmaster rolled into one charismatic package, reflecting an age when celebrities weren’t yet required to seem “just like us.” As a result, people didn’t know what to do with Truth or Dare other than gawk — and boy did they. Arriving during Madonna’s imperial phase, the movie further heightened her notoriety. Until Fahrenheit 9/11 in 2004, it was the highest-grossing documentary in history.

Nowadays, pop docs are often produced in conjunction with an artist’s record label or management team — a glorified PR exercise designed around a curated thesis. (Taylor Swift cares about politics after all! The Jonas Brothers aren’t just Disney Channel twerps!) But Truth or Dare had less to prove. There wasn’t a huge precedent for the level of access that Madonna granted, which makes it both quaint and revolutionary. This is the story of the film’s alchemy, as told by Keshishian and several others who made it happen.

The Tour That Caused a Commotion

Blond Ambition was Madonna’s third tour, launching in April 1990 and encompassing 57 dates across ten countries. Capitalizing on the success of “Like a Prayer,” she wanted a controversy-stoking spectacle that redefined the scope of pop concerts. The show opened with a steampunk homage to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, featuring Madonna simulating masturbation on a velvet bed during “Like a Virgin” (and almost getting arrested for it in Toronto), and ending with an Art Deco segment. Jean Paul Gaultier designed the wardrobe, including the distinguished cone bra. Already outspoken about gay rights, Madonna dedicated one show to her friend Keith Haring, who died of AIDS in 1990, when the disease was still highly stigmatized. In 2017, Rolling Stone called Blond Ambition one of the 50 best tours of the last 50 years.

Vincent Paterson, Blond Ambition co-director and choreographer: One thing Madonna and I talked about that was very important to us was that we change the face of pop concerts. I had directed Michael Jackson’s first tour. It was always about letting the world see him as a solo artist, so we didn’t do a lot of costume changes or big set changes. But Madonna was different. I was constantly going from one [singer] to the other, and the interesting thing was they were always asking me questions about the other one. We really wanted to create a pop tour that was highly theatrical, like nobody had ever quite seen before. Bette Midler and David Bowie dabbled in it, but not to the extent we did.

Joanne Gair, Madonna’s makeup artist: Those eyelashes I made for the Blond Ambition tour book, which Herb Ritts shot, with little balls on the end of them — I made that by dipping broken eye shadow on the stove in a pot with melted wax. I put it on toothpick by toothpick. I would come with ideas: “Do you like these?” And that became such an iconic look.

Paterson: Disney gave us a soundstage [for rehearsals] on the lot in Burbank. Madonna said, “Oh, Warren wants to come in and watch today, and I want to see what he has to say about the ‘Sooner or Later’ section.” He was a nice guy, didn’t say too much. I had her leaning against the piano in silhouette. Afterward, he and Madonna and I met in her little trailer on the lot, and we said, “Do you have any ideas?” He said, “I love it, but what about if you put her on the piano?” We both looked at each other and said, “Sounds good.”

Liz Rosenberg, Madonna’s publicist from 1983 to 2015: There was so much controversy during the tour — the religious iconography and of course that “Like a Virgin” thing. I remember saying to myself, She’s never going to get away with this. It’s not going to work, and then continuing to defend her point of view. She did get away with it, I think, because she wasn’t afraid. We absolutely thought they were going to arrest her [in Toronto]. She had the balls to say, “I’m not changing it, I don’t care.”

Madonna (MTV, 1991): The idea isn’t that I have to top myself, but that I have to expand my own horizons and tackle the next issue or go further in terms of creativity and what it is I want to say and what it is I want to do. I don’t want to just keep doing the same thing and saying the same thing, and the thing is that the issues that I’m interested in life are generally controversial issues.

“I Hope My Nana Doesn’t See This”

Concert films, like Ladies and Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones and Talking Heads’ Stop Making Sense, were standard when Truth or Dare came out. Backstage documentaries, however, weren’t. Bob Dylan’s Dont Look Back — also captured in 16mm black-and-white — was a rare exception. Considering U2’s film Rattle and Hum saw a chilly reception in 1988, no one regarded Truth or Dare as a guaranteed home run. But its natural evolution allowed for a spontaneity that can’t be achieved through premeditation. What some of the media mistook for an elaborate calculation was partly a fluke.

When the movie opened, the idea of Madonna as matriarch became its oft-repeated thesis. Madonna lost her own mom to cancer at age 5, and here she was shepherding a brood of young dancers. (“My little babies are feeling fragile,” she says at one point.) One of those dancers, token straight guy Oliver Crumes III, overcame homophobia and reconnected with his estranged father during the process.

Alek Keshishian, Truth or Dare director: Madonna had seen my Harvard thesis, which was a pop opera of Wuthering Heights. I got a call from Madonna personally one afternoon, and five days later I was on the way to Japan [where the tour kicked off]. Originally I came on just to direct an HBO special with a little bit of backstage stuff. It was just meant to be B-roll. Everything that came after was a surprise. They had talked about David Fincher doing the HBO show.

Gair: It wasn’t until the very last minute that we were told it would be filmed.

Kevin Stea, dancer: When we got to Japan, there were cameras here and there. By the time we got to Houston, they started posting things on the wall saying, “If you are entering this space, you’re allowing yourself to be filmed.” We didn’t really know that it was going to be such a grand project until we kept going and it kept getting bigger. But it was never really solid until I opened Vanity Fair and there was a blurb about the movie that said “Madonna and her gay dancers.” I thought it was about her.

Rosenberg: I was totally against it because I don’t think the world needs to see what goes on backstage. In some ways, the best show you’re going to see is onstage, in front of the curtain. I’m old-fashioned in feeling protective and wanting everyone to see the best of Madonna. I worried that it might not have been in her best interest to show the underbelly of the tour.

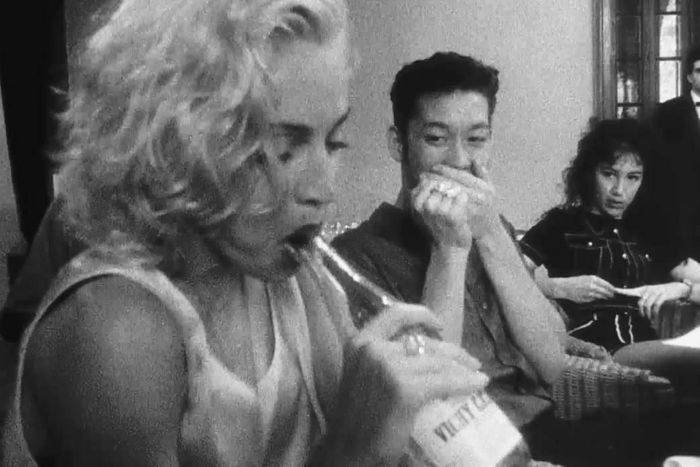

Keshishian: In Japan, I started interviewing the dancers in bed. That was the only way I could make sure they showed up. They generally would wake up super late, go to the venue, do the show, and then they would be out all night. I was just curious about who these guys were. Who are these people who have suddenly landed in Madonna’s world?

Donna De Lory, backup singer: It was, “You’re going to get into bed, and they’re going to light you really well and ask you personal questions.” When that was happening, I thought, They’re going to be telling our stories as well. A lot of us had similarities in our background, coming from parents who were divorced or had addiction in the family. There was a reason we all wanted to be performers and wanted to be loved.

Carlton Wilborn, dancer: It was surprising how in-depth they went with some of the questions, just in regards to our personal lives. There’s so much more that we talked about and shared that didn’t actually end up in Truth or Dare.

Jay Roewe, line producer: The cameraman, Robert Leacock, whose father is Ricky Leacock, who came out of the cinema verité movement in the ’60s [and produced Don’t Look Back], instilled in us that a true documentarian comes in the room dressed in black and you sit around for a while so that people forget you’re there, and then you turn on the camera. That was part of our religion. The cast of characters revealed themselves.

Keshishian: While I was interviewing them, that’s when the cog started working in my brain. I was like, Wait a second. These are all amazing kids. They’re other. In some ways, they’re broken, they’re misfits in the world, and Madonna is playing their mother. That’s why, after Japan, I came back and was like, “Madonna, the movie isn’t what’s happening onstage. The movie is what’s happening offstage with you as the maternal figure to this group of Felliniesque characters.” So I showed her the interviews I had done, and she was fascinated by it.

Madonna (French TV interview, 1991): I looked at the film of me and the dancers and my relationships with the people I worked with and said, “No, this is what interests me, more than my performance onstage.” The audience already got a chance to see my performance on the stage. What they never get to see is life behind the scenes.

Keshishian: Then of course her manager, her agents, everyone were like, “Whoa, what the fuck are you talking about?” What’s remarkable about Madonna is that she didn’t need permission from other people to decide what to do.

Freddy DeMann, Madonna’s manager (Vanity Fair, 1991): I thought she was exposing too much of herself. But Madonna didn’t agree, and when she doesn’t agree, she has a doll and she squeezes it in all the right places and I feel pain. But I was wrong about the movie. It works. The makeup is off and all the gloves are off, and it’s the real real.

Tim Clawson, producer: No disrespect to U2, but I think Alek captured something much deeper than what they put out.

Roewe: The word I would use is “argue.” She and Alek would politely get into things a lot and push back on each other, and that’s why she liked him. He wouldn’t do just what she told him to do. It was a very strong creative dynamic.

Keshishian: Madonna was a control freak, but she had no problem giving up control to another control freak, and I was a control freak.

(Freddy DeMann, Madonna’s manager from 1983 to 1997, said he did not “feel comfortable” commenting for this story. Through her reps, Madonna also declined to be interviewed. Warren Beatty did not respond to requests for comment.)

Wilborn: The “family dynamic” — that’s really something she created. That was a narrative and a positioning for her, and I understand it. It put her in a different power place than everybody else. It served her to have the language be that there was this marginalized group and she could be the savior for it. And while I say that, I want to be clear: It was not a negative. She was sent to do the work of being the voice of reason, being the pillar of strength for a lot of marginalized sectors of people.

Rosenberg: It was Peter Pan and her lost boys, and although she talked about being maternal, she was also one of them.

De Lory: I remember I asked Madonna to show us how she gives head, and I immediately thought, I hope my nana doesn’t see this.

Wilborn: It was a special time to be in her orbit, because she didn’t have any kids and she still had that playfulness. It was really like, Holy shit, is she really going that far and doing all that? Is she really that free? This is off the chain. I don’t know that any of us had ever had a boss who exposed themselves so rawly and playfully.

Niki Haris, backup singer: We were watching her turn into a mega-megastar, but I really got to have normal moments with her: making popcorn, having a barbecue, doing laundry.

Oliver Crumes III, dancer: My dad told me if I don’t graduate he’ll disown me, but once he came and saw the show and realized what I was doing, he was okay with it. I’m grateful and thankful that it did bring us together. I’m glad that was in the movie so people can see what people go through. The tour taught me so much. On the set of “Vogue,” I saw two guys kiss for the first time. Before the tour started, I was homophobic. I wasn’t all with it. Learning from all the guys what their lives were like when they were young was just mind-blowing. If it wasn’t for Madonna and that tour, I would never have got that experience.

Rosenberg: I don’t know if you could tell the level of her commitment to her work and to accomplishing the most incredible show people have ever seen. I don’t know that the film presented that much of that particular component, which I remember very well. Rehearsing two shows a day in the weeks leading up to it was just unfathomable.

The Part About Warren Beatty

Having divorced Sean Penn in 1989, Madonna began dating Warren Beatty while they were making the 1990 hit Dick Tracy. In addition to Beatty, who was 53 at the time, and close friend Sandra Bernhard, Truth or Dare features Kevin “We Thought It Was Neat” Costner, Lionel Richie, Olivia Newton-John, Dick Tracy co-stars Mandy Patinkin and Al Pacino, Pedro Almodóvar, Antonio Banderas, and Rossy de Palma. Madonna understood her gravitational pull within the broader pop-culture universe and behaved without much humility. In fact, she seemed to take pride — and still does — in her acidic wit. “Madonna treated us like simpletons,” Almodóvar later said. Other moments in the film, like a visit to her mother’s grave, were more contrived, with Keshishian miking the site beforehand.

Warren Beatty (People magazine, 2016): When we were going [out] and she was making the documentary Truth or Dare, I said, “I don’t want to be in it.”’ And she said, “Why would I want you in it?’”

Stea: Warren was so over us. He was like, “I’m at a different point in my life.” He was just rolling his eyes whenever we were invited along with her to places. I thought it was so sweet that she would take us everywhere. We went over to Warren’s house to celebrate his birthday. None of his friends were there, but yet there I am with some of the other dancers and Sandra Bernhard. I could tell on his face: “Well, this is what it’s come to.”

Haris: I find him to be one of the smartest human beings, and kind. I love him because he was older. It was nice to have adult conversations. I felt like I was around a bunch of kids.

Rosenberg: I thought, What a guy for stepping into that kind of world. Not that he was unfamiliar with celebrity, but with the mania of a tour of that size, I appreciated him. He adored Madonna and he treated her really well. What is the line from “Express Yourself”? “Long-stem roses are the way to your heart, but he needs to start with your head.” What a great line that is. I would say Warren was very good with the roses and the brain connection.

Paterson: He and Jack Nicholson were such players at that time. They were everywhere and with everybody, and I think it was just as much a coup for her as it was for him. I kind of look at it like she was calling the shots.

Christopher Ciccone, Madonna’s brother, who served as the tour’s art director (Daily Mail, 2008): My sister being my sister, she was acutely aware that being Warren’s girlfriend was wonderful for her mythology, her status in Hollywood.

Barry Alexander Brown, Truth or Dare editor: There were things about Warren Beatty [that got cut]: a conversation between the two of them on the phone that got very intimate. He said, “I’m not exposing myself like that.” There was one sequence in which he was waiting in her apartment in New York for her to get ready.

Roewe: You could have made a short film just on the footage of Warren Beatty in her apartment. We rolled the cameras for 40 minutes.

Brown: My first cut of that was indulgently long. I just found it fascinating to be on Warren Beatty for ten minutes while he’s waiting for Madonna to come down. I showed that to Alek and Madonna, and they were like, “Yeah, that’s enough of that.” I came away impressed by her talent as a filmmaker and her ability to see herself in the third person, which is really difficult to do.

Keshishian: His lawyers were like, “Warren hasn’t agreed to be in this. He’d like to see the film.” And I remember Madonna going, “Tell him too bad because he saw all the signs that we were filming and he’s going to be in it and he doesn’t get to see it.”

Beatty (People, 2016): That [“she doesn’t want to live off camera” quote] captured how I felt. I was kind of touched [that she left it in] because I felt that I said the right thing.

Stea: New Kids on the Block threw a party for us in New York. There was a party in Paris where Lenny Kravitz and Sinead O’Connor came through. There was stuff with her supermodel friends that I thought might be more present [in the film], and there was definitely footage of the dancers running around high in Amsterdam.

Kevin Costner (Los Angeles Times, 2007): I was embarrassed by [Madonna fake gagging after he calls the show “neat” backstage] and kind of hurt by it. I just went back there because I was asked to go back. And I found the best word that I could … She was performing [in L.A.] about three or four years ago, so I decided to take my daughters to see her. I just thought this is somebody they should see … She says [during the show], “I want to apologize to Kevin Costner.” She just said it very simply. … I never wrote her to say thank you, but I appreciate it from the bottom of my heart, and that meant more to me than you could ever know.

Putting Harvey Weinstein in His Place

After 200 hours of behind-the-scenes footage and 50 hours of concert footage got culled down, Miramax acquired the domestic theatrical rights. Harvey and Bob Weinstein’s company was still on the rise, having recently released Sex, Lies, and Videotape, The Grifters, and Paris Is Burning. Harvey wasn’t yet a top-line power broker, giving Madonna the upper hand. Internationally, the documentary was titled In Bed With Madonna in case the concept of “truth or dare?” didn’t translate abroad. In 2005, during Madonna’s Anglophilic phase, she called the amended name “really naff,” British slang for “tacky.”

Despite (or because of) Truth or Dare’s popularity, some critics insisted Madonna’s entire persona was a performance — an accusation she could never fully escape (sample headline: Truth or Dare: Madonna’s Big Lie).

Brown: We were at a test screening of the film. Harvey began to talk to her about his ideas for the film, and she just lays into him: “Listen, I put up the money for this movie. I don’t care what your point of view is. I never want to hear it. Who the hell are you to tell me what kind of film I should be doing? This is mine and Alek’s. Shut up and I don’t ever want to hear another one of your ideas about it.” He just crumpled.

Keshishian: I recall her saying at one point that he did try to kiss her, and she said she pushed him away. Even in public, Madonna was like, “Get away from me, you smell like a fucking ashtray.” In that respect, Madonna was already more powerful than Harvey.

Rosenberg: I think he was a little afraid of her, since he’s into having power over women. He understood he was not in a position to give her shit.

Madonna (New York Times, 2019): Harvey crossed lines and boundaries and was incredibly sexually flirtatious and forward with me when we were working together; he was married at the time, and I certainly wasn’t interested.

(When asked for comment, a representative for Weinstein provided the same statement previously issued to the media, saying, “This was what he said when confronted with it in 2019. Nothing has changed.”)

Keshishian: The biggest thing that Madonna tried to do was keep provoking him in his understanding and acceptance of gay men. She was doing this stuff when it was not popular, and she didn’t give a fuck.

Stea: I was expecting something much more salacious and crazy, but it was really a very good representation of our tour and who we were and who Madonna was. I was really pleased that it showed the quiet moments of hers. A lot of the press almost looked at those quiet moments like they were fake. But I saw a lot more of that than I saw of the big on-camera Madonna. The quieter, more pensive Madonna who had things at risk and was committed to social issues and our relationships — that’s the Madonna I admired, respected, and fell in love with the most.

Keshishian: I would read some of those articles [about the tour and documentary], and it made it seem like she was this marketing genius who would sit at the table rubbing her hands going, “What’s my new persona going to be?” It wasn’t that. It was so instinctive and natural to her. I always likened it to, “Imagine a 12-year-old who runs into the attic and picks up a new outfit.”

Rosenberg: That’s kind of a fallacy that people have. I don’t feel that Madonna had a master plan about how to manipulate the media. She did her thing and she knew she was gonna take shit for it.

Madonna (Vanity Fair, 1991): People will say, “She knows the camera is on, she’s just acting.” But even if I am acting, there’s a truth in my acting. It’s like when you go into a psychiatrist’s office and you don’t really tell them what you did. You lie, but even the lie you’ve chosen to tell is revealing. I wanted people to see that my life isn’t so easy, and one step further than that is, the movie’s not completely me. You could watch it and say, “I still don’t know Madonna,” and good. Because you will never know the real me. Ever.

Wilborn: We’ve got to be careful how we place a person in the hierarchy and how we view them and how we over-chastise them or over-critique what they’re doing. They really are not much different than what the rest of us are doing day to day, but because they have these positions that are so wonderfully monumental in the world, the natural, curious, human phenom is to figure out a way to break it down.

Brown: One of the things that knocked me out is that party they do in France. She’s staying in this great hotel where she has a party for everybody at the end of the tour. Finally she kicks everybody out to go to bed, and she goes around her suite and cleans up. That was one of the last things shot, and I thought, That’s the beginning of the movie. Whatever you might think you know about Madonna, you probably don’t know her at all. Who would have thought that Madonna would clean up her own suite after throwing a party? You can see she’s tired and a little tipsy. It says a lot.

Keshishian: There were a few moments toward the end where Harvey wanted 15 minutes from the film. I was like, “I’m not cutting 15 minutes.” He said, “Look, I just showed the film to Jeffrey Katzenbeng. He loves it, but he thinks it needs to be 15 minutes shorter.” I go, “Well, that’s why we didn’t sell it to Jeffrey Katzenberg. This is a movie, Harvey. This is her life. If I get rid of 15 minutes, it changes your takeaway of her.”

The Dancers’ Lawsuit

Truth or Dare opened on May 10, 1991. Five days later, it had a flashy midnight screening at the Cannes Film Festival. A party celebrating the movie drew the likes of Quincy Jones, Tina Turner, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Eddie Murphy, Billy Crystal, and Spike Lee, who would later cast Madonna in Girl 6. The following year, three of the Blond Ambition dancers sued Madonna and the production companies — one because Keshishian and Madonna declined to remove a scene in which he kisses another male dancer, and the other two because they were not paid for the film. The whole ordeal became media gossip. They settled out of court in 1994. The 2016 documentary Strike a Pose reunited the surviving dancers, many of whom remain friends and feel no animosity toward Madonna. (Gabriel Trupin, whose makeout moment remained intact, died of AIDS in 1995.)

Stea: My involvement in the lawsuit was completely a contractual issue: “Pay the money that’s written out and agreed to in our contracts.” Looking back at it now, I don’t know that she ever knew it was in my contract.

Crumes: I looked at it like I had to protect myself. I didn’t have a contract for [the film]. There are a lot of die-hard Madonna fans that are mad about the fact that we didn’t get paid. It was so much of a vulnerable movie, and it showed every weakness and strength of everyone. Gabriel’s family didn’t know he was gay. We should have all gotten paid because it’s still making money.

Stea: I know how upset she was, and I’m sure they framed it that we saw how popular the movie was and that we were trying to get more money. The choice I made to do the lawsuit was literally because I said, “What would she do? She would fight for herself.” She taught me to stand up for myself — literally wrote on my Christmas present, “Grab life by the balls and don’t let go.” She kept telling me, “Don’t let people take advantage of you.” My agents should have been the ones to sue, not me.

Crumes: The day that we were sitting at the table — me, Kevin, Gabriel, [Gabriel’s lawyer, Debra Johnson], and my lawyer were sitting across from Madonna, looking at her right in her face. I think I said to her, “You know what you did, and I don’t think it’s fair. I didn’t get paid for this.” She’s a kazillionaire. Money is no problem for her.

Wilborn: I was not a part of it. I thought it was inauthentic to do, and the information to justify my position is inside of the movie. Just because you can doesn’t mean you should.

Crumes: It’s water under the bridge for me. No matter what, I’m always going to still love her. Elvis, to me, don’t have nothing on Madonna and Michael Jackson. Sorry! Lady Gaga and Beyoncé don’t have nothing on Madonna and Michael Jackson. Nobody will ever be better than both of them. I have nothing but love for her, and I wish one day I’ll get to see her again.

Stea: In the period when the lawsuit was going on, I was working on Newsies and working with Michael Jackson and modeling for Herb Ritts. Michael didn’t hire me on tour because I was too closely connected to her, but he did make a point of saying something to me like, “Good for you.” Even if I was mad at Madonna, I would always be so grateful and have so much love for her for having brought us together as a group.

A Lasting Legacy

By the end of May 1991, the movie peaked on 652 screens, easily becoming the highest-grossing documentary in history. In addition to a more intimate Madonna, audiences got to see queer men in their element. The same year, comedian Julie Brown, who hosted an MTV series and co-wrote Earth Girls Are Easy, made a parody film called Medusa: Dare to Be Truthful, in which she satirized Madonna as an esteemed egotist. Despite its impact, Truth or Dare didn’t prompt an instant pop-doc wave. That would come 20 years later — a native response to reality television and social media, wherein everyone can chronicle snippets of their lives for mass consumption.

Keshishian: When we were in Cannes, I met Sean Penn for the first time. I was a little bit nervous, like, Is he going to fucking punch me in the face? He just came up to me and goes, “Dude, you got her. You really captured her.”

Brown: Spike Lee said to me, “What, you’re gonna go out and do a Madonna film?” I said, “Yeah, I am. You’ve written Madonna off and you’re wrong about her.” He said, “Yeah, yeah, maybe.” And then next I hear, they’re meeting up in Chicago. Oh, you put her down, but now she’s your girl, right? Later, Spike said, “Yeah, Madonna’s cool, she’s all right.”

Julie Brown, comedian: I had a deal to do a special with Showtime. At first I pitched them something about me trying to get some kind of concert going. Then I saw Truth or Dare, and I was like, “Oh my God, I have to do that.” I’ve always thought performers are hilarious, especially the narcissistic ones. After the special, her agent called my manager and said she really liked it, but then later I heard she was really mad about the cemetery scene [where Medusa visits her dead dog] and the scene where the dancers were suing her, because that really did happen. I just made it up at the time.

Paterson: Madonna laughed cryptically when I told her I knew Julie, then gave me a half-drunk bottle of Champagne for Julie. It may have been Dom.

Brown: It was warm Champagne with a little Post-it that said, “Dear Julie, good luck with your special.”

Roewe: In a sense, Madonna was showing herself to be vulnerable and to be made fun of. That’s one of the things that gave it credibility. It felt real. It wasn’t, “I’m going to tell you the Madonna story.” It was, “You’re going to see the rough sides of me and see me without makeup,” which at that time was not done.

Stea: Alek’s particular vision really paid tribute to gay culture. Being gay himself and sharing the humanity of our community is what gave this movie long-lasting legs and power and iconic status.

Chris Moukarbel, director of 2017’s Gaga: Five Foot Two: I rewatched Truth or Dare as I was filming Five Foot Two so that I wouldn’t veer too close. Madonna and Gaga are such different people, but there’s always going to be natural overlap because of what they do and what they represent. Truth or Dare came out at such a different time in the history of the medium. There were rock-tour films like Gimme Shelter, but I feel like Truth or Dare was the first time that fans had access to the life of a global pop star. I remember everyone being really focused on the fact that Madonna drank Evian water. A detail like that could make more of an impression on audiences because it was so personal and specific.

Brady Corbet, writer-director of 2018’s Vox Lux, in which Natalie Portman plays a volatile pop star: Madonna is just one of countless performers that influenced my decision for the character to have adopted a starkly different cadence in the film’s second half. It gives emphasis to her transfiguration from private citizen to public icon. By the film’s second act, [Portman’s character] is no longer living for herself, so she no longer resembles “herself.”

Keshishian: I’ve spent 30 years saying no to other music docs — a who’s who of pop stars, especially in the first ten years. I could have made a lot of money and probably had a much bigger career, but I just wasn’t interested in repeating myself. Madonna was encouraging people to express themselves, and now a lot of that messaging, while it’s good, is not revolutionary anymore. Everyone’s making their quote-unquote Truth or Dare, but none of it has that impact. By the way, she asked me to do a Truth or Dare 2 many years ago. It ended up being I’m Going to Tell You a Secret. She’d had [her children] Lola and Rocco, and she was married to Guy Ritchie. I go, “Here’s the thing, it’s kind of a conundrum because the logical follow-up to Truth or Dare is to show you now as a real mother, and yet it’s exploitative.” She was like, “No, I don’t want to make that type of documentary anyway. I want people to see the serious work I’m doing for Malawi and my work in Kabbalah.” I remember thinking to myself, Okay, so you want to make an apology film for Truth or Dare, to show how much more evolved and giving she is. I remember saying to her, “The problem is, that’s not a movie — that’s not drama. It’s just an essay.”

Rosenberg: Now, 30 years later, I’m more struck by Madonna’s courage, her desire to change the cultural thinking about religion, femininity, sex.

Madonna (Entertainment Weekly, 2015): I’m afraid to watch it. I just think I’m a horrible brat, that’s what I’m afraid of.

De Lory: My daughter is 18, and in this day and age, she watches that movie and sees nothing but strength. She sees a role model. To be around a woman like Madonna was just like, “Yes!” We felt taken care of.

Keshishian: As Warren Beatty said, “You don’t do this. This is not how you create stardom.” That’s why Truth or Dare worked. No other star had done that yet. Once Truth or Dare did it, you kind of can’t do it again. It’s kind of unfair to expect other people to.