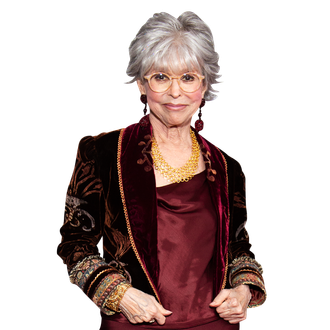

Believe it or not, it took Rita Moreno a full year to agree to appear in a documentary about herself. The legendary actress, born Rosa Dolores Alverío in Humacao, Puerto Rico, had already written a memoir, and performed a solo show about her remarkable life and career, both back in 2011. What was left to say? “Here’s a woman who ostensibly is quite successful and has beaten some odds, it seems,” Moreno, 89, reflects. “But I wanted to reveal something very different in terms of my success and the struggles.” And Rita Moreno: Just a Girl Who Decided to Go For It is a moving exploration of her turbulent, up-and-down career, which saw her going from being cast in a variety of “exotic” parts in genre pictures, to winning an Oscar for 1961’s West Side Story, to achieving the rare distinction of the EGOT, having won an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony. (She was only the third person to have done it at the time.) We talked recently about West Side Story (both film versions), One Day at a Time, and her relationships with fellow actors Marlon Brando and James Garner.

You talk a lot about the importance of therapy in the documentary. How did you start?

Well, here’s the amusing part of it. Marlon [Brando] had been in therapy. We had this almost eight-year relationship. And at one point he said to me, “You need help,” which now makes me really laugh hard because it’s one loony telling the other loony that they need help! It turned out he was absolutely right. It’s probably the greatest favor I ever did for myself.

I recently watched the film you and Brando did together years after your breakup, The Night of the Following Day. Your performance in that film is phenomenal and quite disturbing. I imagine it was an incredible ordeal.

On the whole it was not, but then it came to this particular scene where I had to slap him. I am really very, very bad with striking people, acting or not. I mean, I had a hard time slapping Faye Dunaway once when she was playing a version of Evita for a television series. She really had to make me so angry because I had a hard time doing it. Anyway, so Marlon said, “You can’t fake it. There’s no way you can fake it. Let’s practice a little bit.” And I kind of slapped him, and he said, “Okay, but don’t do any less than that.” But what happened is when that moment came for me to slap him, I hauled off and slapped him. And it was a very emotional scene anyway to start, and I saw his hairline go back about two inches. It was scary. And he hauled off. He was not supposed to hit me. He hauled off and cracked me across the face, and I understood what people meant when they said, “I saw stars.” I really saw sparkling things in front of my eyes. It opened up this well of hurt, and rage, and disappointment, that had been obviously sitting there for years and years and years unexpressed. As I say in the documentary, the pond scum just came right up to the surface. It had been sitting there all these years, and I went berserk. That was for real. I don’t even know what I was saying. It surprised the hell out of him, of course, and he kept trying to defend himself by putting his arms up and all that. The director could not have been happier, so he kept the camera rolling.

Is it tough for you to watch a scene like that?

Yes, it is because I know what I’m experiencing, and it hurts me so much that it took me so long to express what I was feeling. It breaks my heart, actually. And I feel so sorry for that girl on the screen. I really, really do.

I was surprised to read in your memoir that you and Brando continued to be friends to the end of his life.

We did. We had a telephone friendship after that. He did the calling, I never called him, and sometimes he’d say, “Let me talk to Lenny,” my husband, and they would talk for a half-hour. Marlon was famous, as you may know, for long conversations. And long pauses. Toni Morrison could tell you that because they were very good friends — same thing.

Let’s talk about West Side Story.

Which one? I love saying that!

You’re credited as an executive producer on the new one. What did that entail?

Really nothing more than helping Steven [Spielberg] with things that he wanted to know about the original. I certainly wasn’t going to be a producer-producer, but there were things I could tell him that were helpful, not the least of which were Puerto Rican and Hispanic matters. Because he and Tony Kushner were, in the most admirable way, determined to correct the mistakes that were made in the original movie with respect to gender and color and what is a Puerto Rican, what is a white boy. They examined that from every possible angle, to the extent that they actually called the University of Puerto Rico and asked if they could have a panel meeting. They wanted an audience for it, too. There are people there who didn’t like the first movie. You have to admire the respect that was shown this project by these two amazing gentlemen.

It sounds like it took a while for you to get the part in the original film.

It did. I worked so hard to get that movie. I did a screen test, then an in-person audition for the acting part, then an in-person audition for the singing part, and finally Jerry Robbins — whose idea it was to audition me because he’d already worked with me on The King and I — warned me, “Everything is really good so far, but now you have to be able to dance.” He said, “How long’s it been?” I said, “I don’t want to say.” I think the last time was when I was 16, and I was in my middle-20s. And he said, “You just have to understand that, as much as we would love to have you, because so far the auditions have been immensely successful, if you can’t cut it with the dancing, you don’t play Anita.” And they were auditioning anybody with brown hair and brown eyes. So I did something very clever and desperate. I called a girlfriend named Debra, who had played Anita on the road, and I told her what was happening. I said, “I’m going to have an audition in a couple of weeks, and I am terrified.”

But hadn’t you been a dancer since you were a small child?

But I hadn’t danced in forever, No. 1. No. 2, I’d never done the kind of dancing that’s being done in West Side Story — which they call jazz, by the way. (Some people call it modern dance, but it’s really not. It’s jazz.) I was a Spanish dancer. There’s a big chasm between those things. I said to Debra, “So can you help me out?” She was very kind. She said, “Absolutely. But I’m warning you, I can’t teach you the entire dance, there’s just no time. I’ll teach you certain sections of the dance that I think they might teach you.” Because that’s what a dance audition is like: You come in, they ask you to bring a flared skirt, and they teach you brand-new steps you’ve never done in your life. You do it slowly, and slowly, and then you do it a little faster, and then they say, “Okay, now I want you to perform it.” Very scary.

So I went to the audition finally with my heart in my throat, and first the assistant dance director, Howard Jeffries, taught me the steps, and I got to do them well enough, and that seemed to go okay. And he said, “Now I’ll teach you a piece.” Same thing. I was just scared to death. Anyway, I did it. What I found out years later is that Jerry called him and asked, “How did it go?” And he said, “Well, I’ll tell you something. I think she hasn’t danced in a while, frankly. But she is so vivacious. She’s lots of fun. She has a great sense of humor. She has a sense of style, which is surprising given that she probably hasn’t danced much and certainly not this kind. She told me she was a Spanish dancer, which means not a whole lot. But what is really impressive about her is she learns so fast.” Well, I knew the steps in advance!

There’s a very touching anecdote in your memoir about being a young child and dancing for troops who were on their way to fight in World War II. And it’s only later that you realized that was probably the last bit of entertainment some of them saw.

Isn’t that something? There would be a big bell that would ring, which meant they had to board the ships. It was very loud, like a school bell, and then the entire room would literally get up and leave. I would sit and wait until the next little gang of people showed up. I’m guessing I was about 8 or 9, in my Carmen Miranda outfit singing “Rum and Coca-Cola,” and they were a very sweet audience, very appreciative. And they were probably very vulnerable because they knew what was coming, and they were willing to be distracted. Now I get so moved because I was so young, not realizing that at least half of those young men would never come back.

Tell me about the period after you won the Oscar for West Side Story.

That was a heartbreaking period because I just didn’t get to do anything. I thought, Wow, I not only won the Oscar, I won a Golden Globe — which, by the way, was an important award at that time. I thought, Well, this is it. I’m going to get work. This is going to be wonderful. And to my astonishment and dismay, I didn’t do a movie for seven years. That broke my heart. It really broke my heart. I couldn’t understand it. I was always kind of a naïve person, but that just stunned me. It still stuns me. Mind you, I was made some offers, but they were gang movies on a lesser scale, way lesser.

It’s also fascinating, because when you do start doing movies again, the parts are relatively small. Even in a film like Carnal Knowledge, you just have one scene. It’s an extraordinary movie, and your scene comes right at the end, and it’s spectacular, but at the same time, in that cast, you’re the one who has the Oscar. Or in a film like Marlowe, which is a delightful thriller, you’re not even the female lead, you’re like the friend of the female lead. Even though you’d accomplished more than probably anyone in that cast.

You know what? Show business is my life! “She said with a chortle.” [Laughs] It’s terribly sad. Let me tell you, one of the saddest things I read, which of course I didn’t expect, but it makes perfect sense — a couple of critics who loved the documentary actually said, “One wonders with sadness what kind of career she might have had had there not been this curse of the Hispanic thing.” And when I read that, oh man, I got so sad because it’s true. I’ve always felt that. That’s when you really have to fight bitterness and anger. Particularly bitterness.

When you are presented with those opportunities though, what determines whether you do the film or show or not? Is it because you like the people that you’re working with? You won an Emmy for a guest appearance on The Rockford Files, and I know you were good friends with James Garner.

It had nothing to do with liking Jimmy. It was just a fun part. I loved playing her. She had a great name [Rita Capkovic]. And I got a TV award for that, which was marvelous. Jimmy was beside himself. He was so happy. I’ll tell you something delicious that you’ll enjoy. [Years earlier] he was one of the young players that 20th Century Fox was testing to put on contract. They did this then; everybody did a screen test. I was assigned to his scene. And this was on-camera, the whole works, in color. It was a scene from a famous movie [Bridges at Toko-Ri], and he was doing William Holden’s part. I was doing Grace Kelly’s. I thought, Oh man! I’m playing a white woman! Woo! I’m in the right studio! And Jimmy was awful in the test! He was just a country boy. I thought, Oh my gosh! Are they going to sign him? He was handsome as the devil and sweet as could be. They did not sign him. He went on to become Maverick later. There I was criticizing this kid and thinking, Oh my God. Pee-yew. Yes, he’s handsome, but give me a break! I play Grace Kelly, I’m doing that kind of part for the first time in my life, and I get this kid? And of course, we remained friends all his life.

You won a Tony for Terrence McNally’s The Ritz, and you also appeared in the film version directed by Richard Lester. Your character, Googie Gomez, a brash, ambitious, not-very-good-singer with big dreams, is incredible. Is it true that you inspired the character?

She’s something I invented during a ten-minute break on West Side Story. I said, “Okay, this is a Puerto Rican girl who has absolutely no talent and can just get by in English, and she’s auditioning for a bus-and-truck of Gypsy.” And the kids laughed and it was fun. I thought, I’m going to do that more often just as a little party trick. I did that at a party that James Coco was giving when we were doing The Last of the Red Hot Lovers on Broadway. Terrence was a very good friend of his. During the party, Jimmy said to me, “Rita, do that crazy Puerto Rican girl for Terrence. I think he’ll love it.” So I did a bunch of things. He just literally fell off his chair. And then I sang “Everything’s Coming Up Roses.” As he left that night he said to me, “I am going to write a part for that character.” I didn’t believe it. About six months later Jimmy Coco stopped me in the street, and said, “Has Terrence sent you the script?” And I said, “Terrence who?” About a week later, I did get the script. I remember my husband was sound asleep and I was sitting in the bed reading and shaking the bed and waking him up all the time. He got very annoyed, and he sent me out of the room.

Is there a particular medium you, an EGOT winner, prefer?

I think I liked films the best.

Despite everything films have put you through?

Remember, I’m about to be 90, so I have no interest whatsoever in doing eight [theater shows] a week. Never, never, never. In fact, when I did my own show about my life at the Berkeley Rep, I did six a week. I had to do three times as long so they could make their money back, which was okay with me.

You’ve also had a lot of success with TV of late as well, particularly with One Day at a Time. It was frustrating watching all the struggles that show had staying on air. It seemed like everyone I knew really loved it.

Oh, it’s just so sad. It’s so unfair. We know that life is not fair, but I just can’t believe that we couldn’t find the audience. I do feel very strongly that Netflix, as wonderful as they are, did not do the job that they needed to do with it. I think they needed to really publicize this show way, way, way, way, way more than they did. I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but that’s not what they do. I think we suffered terribly from the lack of enough exposure. We needed way more than they provided. People loved the show! Every Hispanic I’ve ever met in my life was watching that show.

Because I grew up in the 1980s, to me your most iconic character might still be the constantly shouting, aggravated director on The Electric Company. That seared into my brain from an early age that this is what directors are like. Of all the directors that you’ve worked with, who came closest to that character?

The person who directed a movie called Seven Cities of Gold [Robert D. Webb]. This is the man who [in a scene where] I was supposed to be dead in the water, hollered at me in front of everybody and embarrassed me in front of everybody because I was being stung by jellyfish, so I was twitching. He didn’t even hear that. “You’re supposed to be dead!”