We whiled away the deathly winter and tumultuous spring laying up expectations for an unruly summer, dreaming of beer splatter on bar nights and the rejuvenating undulations of sound waves sliding out from speakers at live events. But the three weeks since the solstice have been, by turns, oppressively hot and worryingly stormy, portents of stark, terrifying summers yet to come. Outside, relationships are rekindling, but the fallout from quarantine looms heavy as clouds cover. Clubs closed. Jobs vanished. Bridges burned. Friends drifted. People died. Are you noticing ways that you’ve changed as well? Are you more anxious? More guarded? What psychic damage did we accrue in the year we’ll never forget? Are we better now?

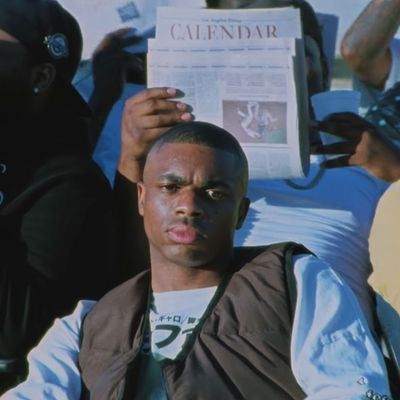

Vince Staples makes music for summers that serve more than beach days and back sweat, where heat’s an ill omen because tempers shoot up when temperatures do. Raised in North Long Beach, surrounded by the intersections written about in West Coast gangsta-rap classics, Vince speaks of life, death, joy, and pain with an almost Zen-like matter-of-factness, as though it’s evenhandedness that tips the scales of fate. It’s true; the best thing you can be in a pinch is cucumber-cool and witty. Staples does so effortlessly, such that he’s known as much for his humor as his music. His Twitter account is a never-ending stream of wry observations about the world and the quirks within his fandom, which loves him but doesn’t always seem to grasp where he’s coming from in the same way that Earl Sweatshirt can puzzle his followers tweeting about his favorite Mary J. Blige song. Like Earl, an early collaborator instrumental in nudging Staples into a career in rap, Vince doesn’t mind being misunderstood. (“I think my favorite thing about music is that it gives you a space to talk through things because I don’t really want to talk to anybody else,” he told actor and writer Jermaine Fowler during a recent conversation in Interview magazine.) His career has been a volley of sharp left turns. Get too cozy with the sound of any release, and the next one will throw you off.

Vince is engaged in a precarious gambit. He’s making very personal and not all that radio-friendly music on a major record label. His 2015 debut studio album, Summertime ‘06, told dark, pained stories over suffocating, skeletal beats from No I.D., avoiding the pop-friendly bombast of the veteran beatmaker’s best-known singles (“Holy Grail,” “Run This Town”) and favoring the minimalist funk of “Dopeman” and “Loca” instead. The follow-up, 2017’s Big Fish Theory, touted collaborations with dance-music luminaries like Sophie and Flume but alienated a portion of the fandom, which received the forward-thinking sounds of songs like “SAMO” as if they’d been given a batch of inscrutable math problems to solve. A year later, FM! delivered a short but alluring survey of modern California rap music — touching on hyphy, Tyga-style ratchet music, Sweatshirt’s insular boom bap, and the rowdy street rap favored by the guys in TDE not named Kendrick — in a brisk 22 minutes. Smoothing these dramatic stylistic turns were effortless flows and unnervingly efficient wordplay. You never know what the new Vince is going to sound like ahead of time, but you always know that his honesty will cut you deeply.

On this summer’s Vince Staples, the artist is trying to tie the restless moods of his back catalogue together, while attempting something that feels new for him. Like FM!, the self-titled album is a 22-minute blast of curt but heavy thoughts about life in the trenches. Like Summertime ‘06, the songs conjure the heat and misery — but not so much the parties and hookups — of July. The production, handled by FM! wingman Kenny Beats, balances the hollowed bangers of Summertime with the careful inroads toward pop made on Big Fish. Unlike any of those releases, though, Vince Staples leans into a melodic, mainstream-friendly style of rap that further complicates matters. The mix of sweet hooks and dire straits seems conversant in (if not respectfully, then parodicaly) the skill set of rap’s current A list; imagine a more restrained, less arrogant Lil Baby, or a Drake freaked out by the comfort of Calabasas. “Are You With That?” frets about bloodshed in neat flows. while Kenny and co-producer Reske serve melted vocal samples and aqueous synth sounds; lead single “Law of Averages,” little more than a bed of sped-up voices and splashes of synths and blips, skewers leeches as Staples juggles threats and puns, shrewdness and kindness: “Everyone that I’ve ever known asked me for a loan / Leave me ‘lone, .44 Stallone get a nigga gone.” “‘Lil Wayne Carter’ what I call my .38 / Kiss your baby in the face if you play with where I stay.” Every song is a two-minute wonder that’s gone after the second chorus. Where FM! went for sprawl, the self-titled is laser-guided and direct.

It’s tempting to see the new album as an answer to the last. In some ways, the world is notably different now than it was in 2018, but in many other ways, it isn’t. The people with the least opportunities continue to struggle and to chisel out ways where ways hadn’t existed. But stakes are higher. A pandemic is good for heightening and exacerbating preexisting social ills. The devilish joy harbored in the feistier moments of FM! — “Who ‘bout that liiife?” — has settled into a laidback delivery more in tune with Vince’s speaking voice than the brash, urgent vocal attack of songs like the 2014 Hell Can Wait EP highlight “Blue Suede.” He’s content just to slip into pockets and keep time, not necessarily bowling over the listener with involved and intricate wordplay, though he’s still capable of impressive feats like the restless cadences of “Take Me Home,” where you catch bits of flows from past rap hits like Method Man’s “Bring the Pain” and Jermaine Dupri and Jay-Z’s “Money Ain’t a Thang,” or the flurry of notes that sail out during “Are You With That?”

The pared-down stuff has gone over a bit weirdly with listeners — by hook or by crook, new Vince music confounds someone. It is wild that the rapper’s most commercial-sounding set would elicit gripes about how well he is or isn’t applying himself, how much he may or may not be dumbing it down, though it does genuinely at times feel like he is doing that. This resembles the kind of music some people wanted Vince to make all along. We always want whatever we haven’t got. But you can’t rap the way Staples does in “Sundown Town” (“We was in the hood, rent was late, ain’t have Section 8 / Had a .38 in the eighth, moved on 68th / Then they put us out, we was sleeping on my auntie couch / Then she put us out, stomach growling, stealing from the Ralphs”) or “Taking Trips” (“I hate July, crime is high, the summer suck / Can’t even hit the beach without my heat, it’s in my trunks”) without having seen some things and lived to tell, without a formidable pen game for the telling. It sounds like a guy expressing displeasure with the state of things as much with his words as with his tone of voice. It sounds the way this summer feels. We’re all out burning up, trying to play it cool, just a degree or two removed from certain death, partying until we can’t anymore.