After Andy Warhol and maybe Keith Haring, Chuck Close is the most recognizable artist in America. His gigantic gridded, pixelated abstract vivisections and dissections changed the face of portraiture in art history. Good and bad, his pictures combine dispassionate mathematical basic skills and a workaday, rote approach with sensationalist Baroque optical pow. His impact on American painting of the 1970s through the 1980s was enormous. Close was a living avatar of a return to painting, an old-school downtown art hero become poster child for the potential of post-minimalist and conceptual strategies to break through to the wider world. What he did took guts, follow-through, doggedness, and a certain amount of bluster, brazenness, and intractability. Close, who, four years ago, was accused of sexual harassment by several women who came to his studio and posed for him, possessed all these qualities in abundance.

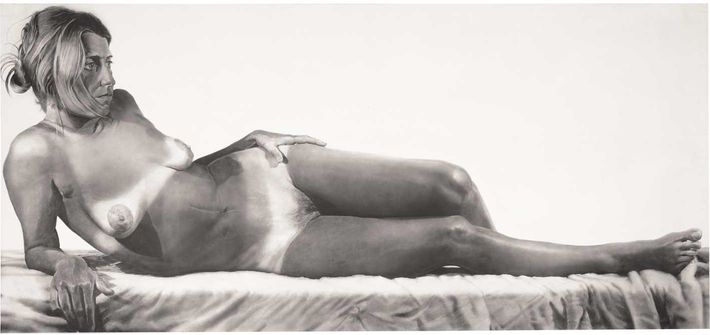

And timing. In 1967, the 27-year-old Yale M.F.A. graduate was living in Amherst. The American art world, meanwhile, was so far up its own ass in isms, ideas, and movements that almost only white men were being lauded and painting itself was declared dead. Figuration was unthinkable. Then Close jumped ship. He stopped making the generic Abstract Expressionist paintings that he and many of his peers were (and still are) making. Bolder still, he turned his back on geometric abstraction, Pop Art, minimalism, and Conceptualism. He created a gigantic 10-by-22-foot, almost monochrome grisaille photorealistic painting of a reclining nude woman. By gridding out the entire canvas and working, as he almost always came to, one little square at a time, Close was rendering the distortion of the camera lens but at the same time in a way that was clearly handmade. It was almost unfinished in that it could never be as surfaceless and almost immaterial as a photograph. Then he destroyed the painting. I can see why. The first time I saw CloseÔÇÖs work, even though it was ten years later I had my mind blown trying to figure out if it was poster art, photography, superrealism, kitsch, air-brush illustration, or fine art.

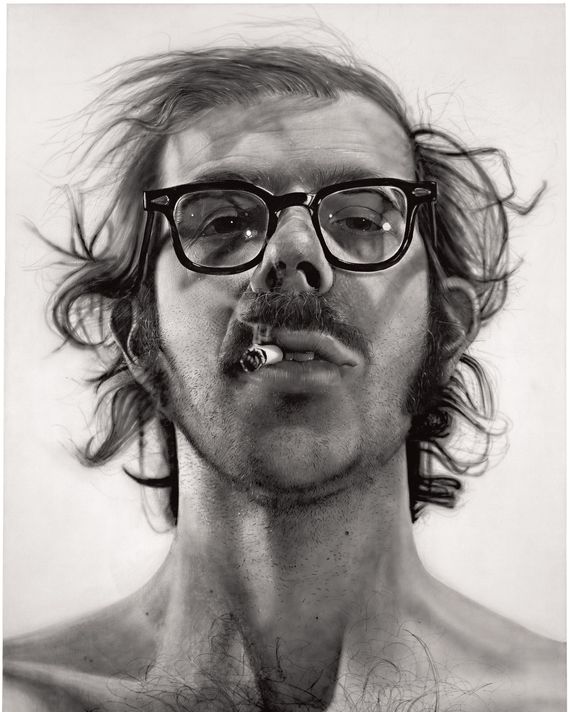

In 1967, he moved to New York, becoming one of the early artists settling in Soho. He soon painted his huge iconic vertical black-and-white hyperrealist image of the disheveled, defiant artist ÔÇö himself ÔÇö with a cigarette between his lips. It was 1950s movie-poster Brando tough, a billboard, hand-made photography, and commercial art, all meeting up with WarholÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Most WantedÔÇØ portraits and his pictures of the damned like Marilyn and Liz. But the obvious step-by-step, square-by-square process tied him to post-minimalists like Sol LeWitt and Dorothea Rockburne, whoÔÇÖd devised visible and conceptual systems to make their art. The next year, he painted a massive face of a tough-looking Richard Serra filling a canvas border to border, edge to edge. You got little in terms of subject matter other than a male face. There was, and never would be, any background or accoutrement or narrative in a Chuck Close painting ÔÇö just the fact of the face. It toggled between retinal thrill and mystery and ontological mystery. Close was an artist mutineer.

Close hadnÔÇÖt taken the bait of the certainty of the death of painting. Instead he referenced and deployed all the above-mentioned downtown movements but forced all these supposedly ÔÇ£radicalÔÇØ things through the nominally conservative duodenum of painting and figurative painting itself. Rather than the many artists trying to make the last painting, final┬ásculpture, perfect artwork, or whatever statement piece, Close wanted to reenter the river of art history. Others grasped the enormous potential of what heÔÇÖd done. Close devised an art that was smart, challenging, avant-garde, uncanny, insistent, implacable, but infinitely accessible and even user-friendly. As someone with no degrees and coming to art late, I really identified with the ideas in his work. I thought of him like a drummer or a place-kicker in football: someone who I knew had skill but nevertheless made me think ÔÇ£I could do that.ÔÇØ By the time he added color to the work in the 1970s ÔÇö and exploded into other processes, especially with his prints and drawings, he was an art star. He didnÔÇÖt have his first solo show until 1970 but had already sold work to a museum.

Catastrophe struck him as he was leaving Gracie Mansion on December 7, 1988. He was struck by a pain in his neck and walked to a nearby hospital. By the next morning, he was paralyzed from the neck down. It would be hard to overstate how saddened and shocked the art scene was. Close was a Soho neighbor, a regular at events, a member of┬ámuseum boards, someone who sat on juries, a beloved teacher and lecturer. I remember being at a dinner at the Long Island home of the legendary gallerist Klaus Kertess ÔÇö among the first in the 1970s to show Close, Lynda Benglis, Brice Marden, Dorothea Rockburne, and many others. The door opened. CloseÔÇÖs then-wife, Leslie, walked in. Behind her I saw Close heft himself with great difficulty out of his wheelchair. He struggled to stand, mounted himself on huge crutches and very slowly made his way to the dinner table and sat down. It was heroic. This was his defiance, pride, will, and doggedness made flesh.

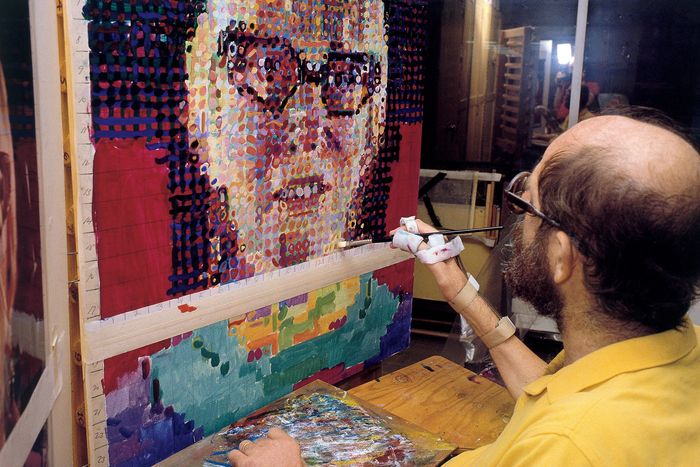

Soon he taught himself to paint again by strapping brushes to his hand and wrist. He constructed a huge moving easel in his studio and went back to work. The catastrophe brought a needed change to the art that had started to turn predictable. He started to paint in looser, less finished, more raw, abstract ways. He made thousands of little abstract painted squares and triangles and shapes inside other little abstract shapes. All these broke down into individual units that simultaneously came together in a painterly kaleidoscope to create a legible face. Close claimed that he had prosopagnosia, the inability to recognize peopleÔÇÖs faces. The new work gave form to that idea of seeing, knowing but not recognizing.

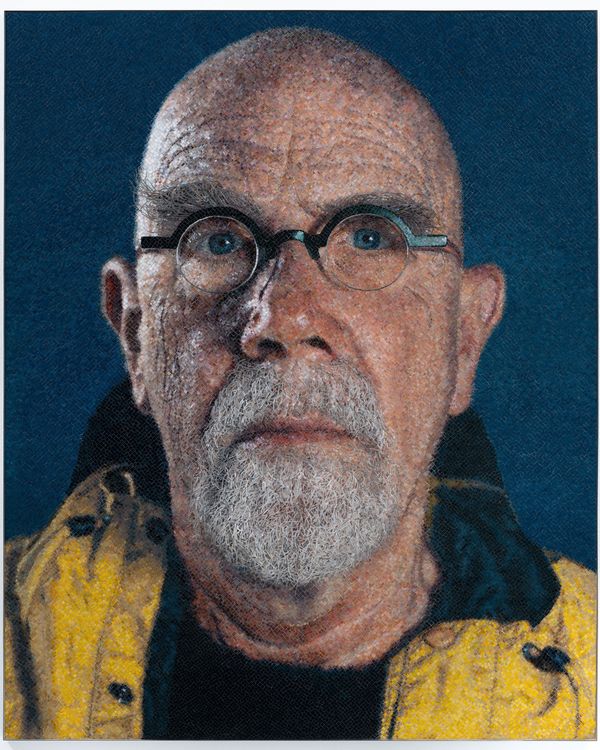

This was essential to me. I had grown tired of CloseÔÇÖs predictable method, touch, subject-matter, scale, framing, and surface. ItÔÇÖs a testament to his tenacity that he kept painting and found another way to do it. However, within another ten years or so, this style too grew optically familiar, repetitious, flat, similarly systematized, at the same scales, with the same colors. He did branch out and painted new waves of artists like Kara Walker, Cindy Sherman, Cecily Brown, and others. A few years after receiving the National Medal, he painted Bill Clinton. He delved deeper into his extra-large Polaroid pictures, many of them beautiful, many others creepy in their scopophilia for the female nude. He photographed Brad Pitt and Kate Moss. For me, however, his work ossified, turning emotionally empty, claustrophobic, untested, on autopilot. Maybe itÔÇÖs my own timidity as a critic, but I never wrote this. After his paralysis and my doubt that IÔÇÖd be able to do in his shoes what he did, I felt it would be snotty and mean.

Even as his work grew less inventive, Close only became more famous. For decades, he was seen everywhere in his high-tech wheelchair, going to every show, stopping in every restaurant, talking with anyone and everyone. At every opening I saw him at, he was surrounded by young artists paying homage. After his death, Instagram was inundated with selfies from artists all over the world of themselves standing next to Close in his chair. He took to wearing flamboyant colored dashikis. For a time, he was mischievously referred to as ÔÇ£Mayor of Soho.ÔÇØ

In 2017, Close was accused of sexually harassing several women, the first in 2005. They reported being invited to his studio to pose, where Close treated them inappropriately.┬áIn an interview, Close sounded a terrible note. He stated, ÔÇ£If I embarrassed anyone or made them feel uncomfortable, I am truly sorry, I didnÔÇÖt mean to. I acknowledge having a dirty mouth, but weÔÇÖre all adults.ÔÇØ Then he added something disgusting that hit home for my own perceptions of CloseÔÇÖs snarky imperiousness and sense of himself: ÔÇ£Last time I looked, discomfort was not a major offense.ÔÇØ In a way, I never went back to his work again. (I remembered him being snappish with me, complaining that IÔÇÖd never written about his work and then claiming he got me the job that I have now. I saw him argue with other artists at Pace once. It all started to add up.) This week, the New York Times reported that he had been diagnosed with AlzheimerÔÇÖs in 2013, and his neurologist noted that ÔÇ£sexual inappropriatenessÔÇØ is a common presenting symptom. Regardless, the art-world reaction was swift. Overnight, Close became artist non grata. His work disappeared from certain public collections; a major retrospective was canceled.

Since his death, with admiration and mixed feelings, I found myself thinking back to that great 1967 breakthrough of sheer nerve, Big Nude, and CloseÔÇÖs act of destroying it. Then I remembered a series of panels and lectures at the Puck Building that I participated in. There, ABC anchorman Peter Jennings was about to interview Close and asked me back stage, ÔÇ£What one question would you most want to ask Chuck Close?ÔÇØ Starstruck, and without thinking, I blurted out, ÔÇ£I want to know why he destroyed Big Nude and started only painting faces.ÔÇØ I went back into the audience and watched Jennings ask my question. It fell flat. Close, almost never at a loss for words, stopped, stuttered, laughed it off, and never answered. Other than feeling the fool, I never thought about it again. This week, I wondered what might have happened if, in addition to his one subject, heÔÇÖd also eventually opened up or returned to this other obviously powerful gate. Instead, with his highs and lows, for more than a half-century Chuck Close looked away from the body and fixed his gaze on the face like no one else in art history.