At first, it’s hard to distinguish between the ebullient mood of the first-time-back audience and the rhapsodic vibrations of the show itself. The first play to open on Broadway since the 2020 shutdown is Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu’s Pass Over, and the night I saw it, a several-minute ovation preceded the show. Even before the curtain rose, the turn-off-your–cell phones announcement prompted a wild round of applause, with people shouting and stamping and raising their hands over their heads in jubilation. Anyone who has seen Nwandu’s work knows there’s a combustible quality to her writing. It was almost frightening to be in an audience so full of open flames.

Pass Over is two plays at once — a successor to Samuel Beckett’s 1953 Waiting for Godot, and a surreal portrait of Black comradeship in the face of white homicide. Two young Black men dream of escaping their bleak urban corner, though they seem eternally trapped there, sleeping and waking under a streetlamp that shines like a sick moon. Moses (Jon Michael Hill) is the leader, while the more easily dazzled Kitch (Namir Smallwood) teases him — or reminds him — that having a prophet’s name confers a certain responsibility. The two are deep friends, their rhythms exactly in sync, joking and riffing and sharing their hopes for the Promised Land, even if they don’t always agree:

MOSES: man caviar is fish eggs

KITCH: yo what

MOSES: yeah nigga damn tiny ass fish eggs

KITCH: ugh

MOSES: dis nigga

KITCH: yo moses man i ain’t know

MOSES: cud write a book with all da shit yo ass don’t know

KITCH: prolly be more like ten books

MOSES: yeah you right

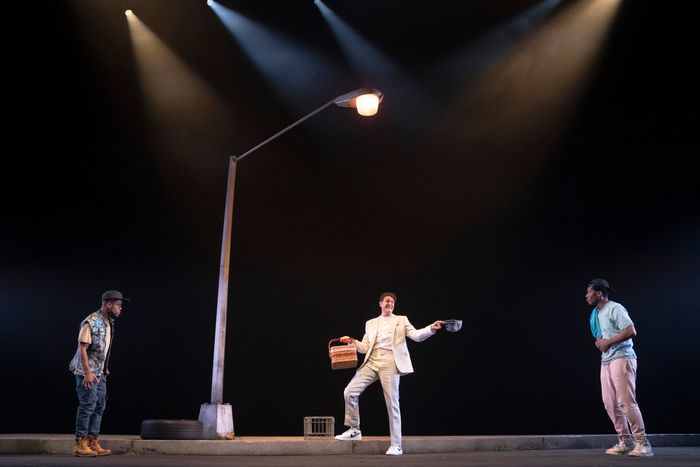

Hill and Smallwood throw the dialogue back and forth lightly, loose as dancers during a warmup. Beneath their grace, though, they’re constrained by an awareness of the police. The stage is set (as many such absurdist plays are set) in a hazy black void, but it’s the invisible whiteness all around them that’s the existential danger. A powerful fear of being shot — registered as a kind of force field — stops them each time they try to leave their patch of concrete.

As they’re rallying their courage to go, a white man, Mister (Gabriel Ebert) wanders by. He’s in a pale suit and a doofy aw-shucks grin, carrying a picnic basket like a Little Red Riding Hood who has a golf date. Is he lost? Is he, hell. He’s the kind of guy who magics a whole feast out of nothing, then quotes scripture (the musical Oklahoma!) for his own purposes. He’s the kind of guy who gives “scout’s honor” that he would never be racist. He’s the kind of guy who would just really like to know why the two Black fellas get to use the N-word and he doesn’t! You know him, or you should — the devil loves a crossroads. Ebert returns in the second half of the play as a violent cop (called Ossifer in the script), and his snarling aggression forms a kind of twin system with Mister’s gosh-golly-gee bonhomie. One white man smiles, the other sneers, but they’re gravitationally connected — one threat swings out of sight, and you know the other is about to orbit into view.

In Waiting for Godot, according to Vivian Mercier, “nothing happens, twice.” The tramps wait; the tramps wake and wait again. Beckett’s play is as much about the cruelty of life’s repetitiveness as it is about mankind’s little shuffle ball change through the mortal coil. Moses and Kitch deliberately recall Vladimir and Estragon from Godot, their black baseball caps echoing the older pair’s bowler hats, and both dramas balance on the delight of seeing a rat-a-tat comedy duo killing time, sharpened by the melancholy knowledge that time is really a killer. Nwandu’s deft twist is to make her pair young. Beckett’s tramps have grown old in their waiting, and Nwandu’s superimposition of our own world on Beckett’s helps us see the tragedy: Young Black men in America are just as exhausted and catastrophically resigned as old men worn out by life.

There are at least three, possibly more, versions of Pass Over: the Chicago premiere; the 2018 New York debut at Lincoln Center; and now the Broadway bow. The Lincoln Center production and this one are similar in many ways, with the one-two punch of Hill’s charisma and Smallwood’s charm still keeping the audience stunned against the ropes. The encounter with Mister was already one of the theater’s great scenes, and it hits even more powerfully on Broadway, where it can expand to fill the enormous room. Ebert and Hill and Smallwood and director Danya Taymor and Nwandu keep the tension rising and rising, Mister’s gleeful Leave It to Beaver exaggerations (Gee!) the source of an almost unbearable — but still hilarious — menace.

In moving to Broadway, Nwandu has, while redrafting, given the script a new ending. Nwandu was raised in (and left) the Evangelical church, and a sermonizing energy is certainly at work inside the play. It exhorts and exposits; it kindles the faithful. In changing the conclusion, though, she seems to be deliberately acting more as pastor than as preacher, taking care of herself, her cast, and her audience by eliding the earlier version’s most hopeless moments. Some of these new, final scenes do still feel a bit improvisational. The flawlessness of the earlier sections falls away, and we can almost hear the “let’s try this?” of the rehearsal room. But I think the awkwardness of this happier ending might actually be the point.

I had been trying to work out what it means that Pass Over is the opening bell for this odd Broadway season. For much of the show, I thought it must be due to its gorgeous gravity, or its exquisitely syncopated language (poetry that uses the N-word more than 260 times), or its challenge to its audience. I thought, a little shallowly, that it was cool that we were starting with such a muscular play, when there is a lot of feel-good tinsel that producers might have thought was appropriate instead. But then, about two-thirds of the way through the night, someone coughed, and my heart froze. I had briefly forgotten that the world is still in a pandemic, and this fall we’re all heading out into the desert without a promise from God.

Just as my anxiety was climbing, Moses started saying things I had never heard before. I had seen and read the 2018 version of the play half a dozen times, yet here it was, changing and becoming new. The scenes seemed a little rickety; the play’s sudden expansion beyond the street corner disrupts its perfect Beckettian aridity. You can actually hear how hard it is for Nwandu to build up joy, because the new section is so transparent about its aesthetic effort. I wondered if she might still be working on the ending — whether, perhaps, she’ll be working on it forever. How right, therefore, that we were at the August Wilson with her, hoping — with clenched stomachs and fast-beating hearts — we will be allowed to write a happy outcome, too.

Pass Over is at the August Wilson Theatre through October 10.