The power lies in his hooded eyes. Large, dark, and — to use a stereotypical descriptor sincerely — inscrutable beneath thick brows frequently tilted in angles of unspecified melancholy. When they draw you in, it suddenly becomes a little hard to breathe. You can’t look away. You find yourself thinking that if he quietly told you to burn your house down, you’d probably do it with a smile. He’s undeniably handsome, but his physical appeal on its own might be best described as “uncle next door.” It’s his virtuoso presence — the way he speaks with his eyes — that transforms him into someone that makes you whimper “daddy.”

Tony Leung. I must admit that I was surprised to learn that 2021 marks the iconic Hong Kong movie star’s Hollywood debut. I assumed that he, like numerous other Asian cinema superstars, had at the very least done a high-profile cameo in the way of Bingbing Fan, Xun Zhou, and Donnie Yen, or starred in a cheesy B-flick like Chow Yun Fat and Boa. But on second thought, of course Tony Leung couldn’t have been bothered to participate in the frivolities of Hollywood until the age of 59. After dazzling audiences in Asia for so long, he didn’t seem to require the attention of the English-language press, where Bingbing Fan, once the highest-paid actress in China, is constantly referred to as “the X-Men actress.” American audiences largely live in their own galaxies, unfamiliar with the blazing suns that light up the screens of Asia.

Despite Hollywood’s track record with Orientalism, however, I felt cautiously optimistic about Leung’s Hollywood debut, in the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s first Asian-led entry Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings. I must admit I screamed a little when Tony Leung’s bedroom eyes did their thing in the trailer (that look that passed between Leung and co-star Fala Chen seemed to contain a century’s worth of devotion). I knew then that I would have to make an effort to root for Simu Liu’s Shang-Chi, the titular hero to Leung’s anti-hero, when I finally watched the movie. Indeed, when American audiences meet Leung, he is outacting his co-star as a grief-stricken warlord whose humanity and monstrosity wrestle within him. At times it feels like director Destin Daniel Cretton has forgotten who his protagonist is, so moving is Leung’s portrayal of sorrow.

I myself have been lucky enough to have drooled over Leung’s onscreen smolder for years, admiring the way he embodies a Hemingway iceberg; the bulk of his characters’ thoughts, memories, dreams, and desires all lurk heavy beneath his surface. You can do no wrong in casting Tony Leung, whether the role is a meticulously written character in a tightly scripted movie or is part of a shoot that has no script to speak of. He will deliver soul and magnetism, whether in a splashy action blockbuster, a trippy arthouse romance, or a taut psychological thriller. He has range (and 60-plus movies under his belt, not including his famous TV work), but you’d be hard-pressed to find Leung playing a character who’s not a moody man of few words. Perhaps on some level he is typecast, but who can blame the directors? When you put Leung in your movie, you must give him room to stare, preferably with a cigarette.

There are four directors who seem to really understand this power of Tony Leung. First up is John Woo, whose two-part Three Kingdoms epic Red Cliff (2008–2009) stars Leung as Zhou Yu, a brilliant general and tactician who prefers making music, and making sweet love to his wife, to making war. The film itself is bloated, tonally inconsistent, and overly campy, but if there’s one thing it got right, it’s using Leung with the utmost precision — in frequent close-ups, with mood lighting.

A scene where Zhou Yu matches wits against Takeshi Kaneshiro’s Zhuge Liang in an impromptu zither duet is set within a dark chamber lit only by the glow of oil lamps. As the zither strings begin to vibrate, the twanging notes rising, Leung’s eyes are trained on Kaneshiro, a smile on his lips as instant recognition of an equal, a worthy opponent he can devour. His face, framed by flickers of flames and edged in gold, stares through the screen right into your soul. When he looks down at his instrument, shoulders squared and brows knit in concentration, his wife watches with a certain knowing look on her face. She understands exactly how that zither feels. Leung reaches the climax of his tune with strong, escalating strokes. Though the scene is meant to communicate the two men’s opposing positions on war, their exchange is undeniably sensual, leaving everyone’s mouth a little dry.

Then there is Ang Lee, whose espionage masterpiece Lust, Caution (2007) gives us Leung’s turn as Mr. Yee, a Chinese high official betraying his country to Japanese invaders. It’s his only truly villainous role prior to playing Wenwu in Shang-Chi. Even so, Leung manages to make Mr. Yee someone for whom we’d betray our country, if he’d only look at us like we were the only good thing in his life. Throughout the film, Leung telegraphs the character’s personal capacity for cruelty. Mr. Yee’s suave manners are constantly veined with a cold menace. He’s a snake — smooth, coiled, poised to strike — and each of his visits to the mah-jongg table alongside blinged-out housewives plays like a viper gliding through a chicken coop.

During Leung’s first one-on-one with Wei Tang’s Jiazhi Wang, the amateur spy who becomes his lover/victim, we watch as predator circles prey. The two have dinner in an upscale restaurant, and Mr. Yee appears aware of something off about the alluring woman sitting across from him. Yet Leung slumps relaxed in his chair, his gaze cool and his body still as he simply watches Tang.

Leung seems to grow in power in the darkness of this movie. While Tang’s character chatters on to fill up space, Leung only smirks and bids her to speak more. Is she succeeding in seducing her mark? Tang’s character seems to think so, but we see a mixture of hunger and amusement in Leung as he observes and interprets her every move, planning his next. When Tang sips her cognac, leaving lipstick on the glass, the camera cuts to a close-up of Leung’s face, his eyes flicking to the damning red stain that betrays her less-than-refined true identity. A barely perceptible look of pity flashes across his face. We learn in that moment that he does not hunt for pleasure, but harbors pieces of a tender heart buried deep beneath his drive to survive at all costs. A tortured villain we all wish we could save.

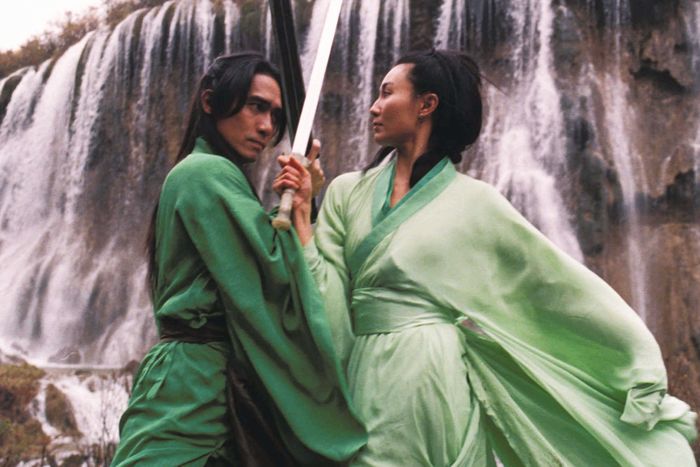

In Yimou Zhang’s accidentally high-camp martial-arts fantasy Hero (2002), Leung plays a legendary assassin and, along with the rest of the gorgeous cast, gamely broods through each color-blocked chapter of a movie that is mostly style and little substance. Reunited with frequent screen partners Maggie Cheung and Ziyi Zhang in a doomed love triangle, Leung’s Broken Sword is preoccupied with the fate of the world. He has plenty of cause to glare into the middle distance for long stretches without saying a word, lost in thought. One moment clad head-to-toe in crimson red, another in sky blue, his long hair forever whipping in the wind, he is the constant eye candy fed to us to make the stilted plot go down easier. (The movie was nominated for a Golden Globe and an Oscar.)

During the “red” chapter of the movie, a battalion of archers rains arrows down on a defiant calligraphy school for refusing to yield to the conquering army. While Cheung and Jet Li’s characters deflect them using what could only be described as wuxia magic, Leung dips the biggest calligraphy brush you’ve ever seen in vermillion ink and writes the Chinese character for “sword” on a massive white sheet (like I said, high camp). The room is dim, with daylight filtering through the papered windows, highlighting Leung’s tall cheekbones and sensuous lips. Slow strings play at full blast while gusts of wind cause Leung’s loose, chest-length hair to whip back and forth as he commits his entire body to this dance of calligraphy, imbuing each stroke with his fire. The camera cuts between full-body shots of Leung and close-ups of his face in total concentration, and whether you think this movie is a poetic masterpiece or oversaturated propaganda, you still find yourself mesmerized by that look of weary piety in his eyes, as if the passion he feels hurts him at every exertion. In a movie that tells a story of navigating duty and desire, it took a talent as great as Leung to honestly express the unbearable weight of it all.

The fourth director is Wong Kar-Wai, whose In the Mood for Love (2000) is one of seven collaborations with Leung, about, as the late Roger Ebert describes, people “[who] are in the mood for love, but not in the time and place for it.” The film, which earned Leung the Best Actor award at Cannes, is famous for its evocative beauty on every level, so it’s difficult to choose just one instance of Leung setting the screen ablaze. But there is one short scene, set at the red-curtained hotel where Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung’s characters regularly meet — not to cheat on their respective unfaithful spouses, but to torture themselves and each other with desire. The film’s signature song, “Yumeji’s Theme,” is all we hear, beginning with steady plucks of strings, leading into a melody of one sad, isolated violin.

Our lovelorn leads move in slow motion, bathed in yellow light so that they look as if they’re submerged in golden syrup. Cheung looks over her shoulder from the doorway of the hotel room, her face a resolute mask. Due to the shot’s shallow depth of field, Leung’s face is out of focus when he meets her in the doorway, but sharpens as she struts past him into the room. Their only real interaction is the pregnant pause during the meeting of their eyes, establishing a mutual understanding of their desperate undertaking. Leung doesn’t move a muscle as she walks by, but he keeps her in his peripheral vision, as if he’s waiting for her to walk right out again. Or perhaps he’s afraid of what will happen next, if some new development will upset their unusual, delicate arrangement — if they end up crossing lines they swore they wouldn’t cross. In this scene, Leung’s character is so deeply vulnerable, so tense with emotions that he seems to be one of the string instruments playing the score, a cello perhaps, tightly wound and vibrating at a low pitch. The tragedy of Leung’s character is his inability to unwind, to let go of the fears and an idiotic sense of propriety that keep him from giving into love.

We often talk about great actors and their ability to deliver their lines, but more should be said about those who make do with the fewest words, or none at all, as Leung has mastered over his nearly four decades before the camera. Perhaps I am greedy, but in Shang-Chi there seemed to be too few moments of wordlessness and too many expository monologues — in Mandarin, no less, rather than Leung’s native Cantonese. But in the beginning of the movie, we are treated to a thrilling and flirtatious battle between Wenwu and his future wife, in a martial-arts sequence reminiscent of the intimate dialogue of limbs between Leung’s Ip Man and Zhang Ziyi’s Gong Er in The Grandmaster. As Leung and Fala Chen engage in a playful dance, it is cut with slowed-down moments of compromising poses and explosive glances, all amidst swirling leaves and beams of light. The whole scene is so smooth and so romantic that it feels like it is lifted right out of a Korean drama, one of the highest forms of modern Asian romance. It is enough to make you forget Wenwu is a centuries-old war criminal.

If you are like me, you might spend the rest of the movie wondering if this man who looks at his love with such affection is a villain who must be defeated, or one whose salvation we should be praying for. It is hard not to fall in love with Tony Leung.