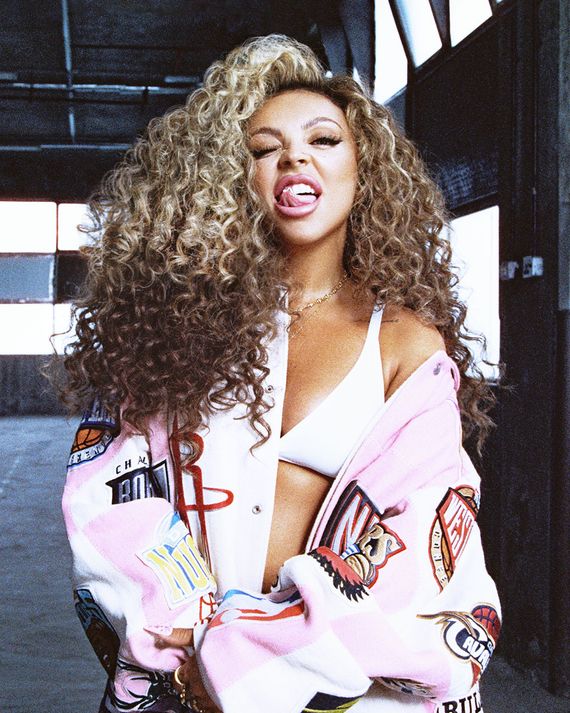

This is what Jesy Nelson has always wanted. She’s sitting on a leather sofa in an East London photo studio, leaning back in a camouflage jacket and cargo pants, dark hair waved, lips overpainted in coral, living her new life. Or rather, her old one. Before she was in Little Mix — the wildly popular band Nelson left at the end of 2020, citing the “constant pressure of being in a girl group” — she was dressing like this, listening to music that sounds similar to the material that she, now a solo artist, is making.

When Nelson was 19 years old, a year before reality television made her one of the most visible stars in Britain, she was bartending one Saturday night in Dagenham, about a ten-minute drive south from her East London hometown of Romford. It was 2010 and she was watching Cher Lloyd successfully audition for The X Factor with a jolty, half-sung Keri Hilson version of Soulja Boy’s “Turn My Swag On,” her top lip curling and hand waving away her haters. For fuck sake, Nelson remembers thinking, this girl is what I want to be like. The following summer, she auditioned for the show — which had launched the careers of One Direction and Leona Lewis — with her version of “Bust Your Windows” by Jazmine Sullivan, wearing a baggy T-shirt, cargo pants, and basketball sneakers. She got through with the seal of approval from three of the judges (the fourth, Gary Barlow, called her audition “generic”), but didn’t make the cut at boot camp as a solo artist. (The shedload of axed contestants were rarely told why.)

Backstage, producers tried piecing her together with other rejected soloists to form a group. “I was always in and out, in and out,” she says. There was one group that felt the most natural to her, though, where her role was clear. “I was with a load of boys, and I was meant to be the ‘Fergie,’” she recalls. “If I was ever gonna be in a group, that’s the group I would have imagined being in.” Fate — or more like Simon Cowell, who executive-produced all of the show’s 15 seasons — had different plans for Nelson. Eventually, she was matched with the spunky Northerner Jade Thirlwall; star-in-the-making pop vocalist Perrie Edwards; and Buckinghamshire-born Leigh-Anne Pinnock, who sang Rihanna’s “Only Girl (in the World)” for her audition, together forming the group eventually known as Little Mix.

As a new foursome, they plowed through to the show’s finals, finding friendship as bandmates in the process, before eventually becoming the first group to win it. It marked the start of a transition for Nelson, from a teenager obsessed with R&B and hip-hop, and the way the stars of those genres dressed, to becoming part of a British pop behemoth. Little Mix’s DNA, released in 2012, remains the highest-charting debut album by a British girl group on the Billboard 200; they have, so far, secured 11 U.K. No. 1 singles; earlier this year, they made history as the first girl group to win the Brit Award for British Group, to the Spice Girls’ delight. Nelson spent nearly a decade with these young women (who have continued on as a trio) wearing corsets and stilettos, touring with Ariana Grande, singing music incongruous to her tastes. Still, she says she enjoyed the years they spent together — up until she didn’t anymore. A decade later, Nelson wants and is finally getting a do-over.

Does preparing for the release of your first solo single feel like a new sort of wish fulfillment, something you were working toward before Little Mix even existed?

Yeah, it does. Don’t get me wrong, I obviously loved being in the girl group, it was amazing. But unless you’re my friends and family, you don’t properly know me. My passion is R&B and hip-hop from the ’90s and early 2000s. That’s what I grew up on. It’s the music I’ve always wanted to make, so it feels quite liberating.

At this point, do you think if the pandemic hadn’t happened, you’d still be a part of Little Mix?

I think so. I wouldn’t have had time to realize that being by myself and doing things that make me happy was what I genuinely wanted to do. I just kept going and going. But that’s what was making me so depressed. I wasn’t looking after myself. I feel like a weight’s been lifted off my shoulders now. For the first time in ten years, I’m in control of my life. As much as we had a say in the music and what we wanted to wear — I didn’t get to choose what to do if I wasn’t feeling good. I couldn’t take a day off. I didn’t have the choice of waking up and saying, “You know what? I don’t want to do that today.” I had three other people to think about.

Did you feel like you were obliged to be there?

It wasn’t that I’d rather be doing something else, it was just for ten years I was under so much pressure, mentally. When we were in lockdown, I had time to myself and it was the happiest I’d ever been. Jade, Perrie, and Leigh-Anne couldn’t wait to get back to work and I was dreading it. It was the first time I’d been able to spend time with my friends and family and eat and do what I wanted. My heart felt happy, but when I went back to work I felt miserable. I knew it wasn’t right.

Had you started envisioning what your solo career would look like before that moment?

Never! Speak to Jade, we could never imagine us not being together. If [someone] ever spoke about it, me and Jade would be petrified at the thought.

It was March this year. That was when I first wrote the single. I got a phone call from my friends who I’ve done the majority of my album with asking if I wanted to go into the studio to take my mind off things, write for other people. I went into the studio and wrote the first single. I kept going in and more songs kept coming. I knew it felt right, like it was meant to happen.

The change of labels in 2018 from Syco to RCA, you’ve said, catalyzed a lot of your issues with being in the band in those final years. Were you alone in those feelings?

No. We’d obviously been [with Syco] since we were, like, babies. Everyone was so invested in us, and the team had become like our family. Everything we’d ever made, they were so passionate about it. Then we changed labels, which wasn’t our choice, and they were a great label, but there wasn’t that same passion like when we were at Syco. We were getting given songs and, for me, I didn’t feel like it was true Little Mix. We were being told, “Go on this [track] because it’s got this person on it.” I don’t want to be in a situation where I’m just putting it out ’cause it’s got a certain artist on it. I want to love a song and believe in it. And I was always very vocal about how I felt. If I didn’t like a song I’d be like, “I’m not going on this.” I’m a very honest person. I can’t be fake.

Were there lots of naysayers around you at that time?

I’m not gonna lie, the team I had when we were with Little Mix weren’t the nicest people to be around. But now I’ve got the most encouraging team. I wake up every day knowing I have people who believe in me.

When we speak, Nelson, now 30, is weeks away from releasing her first solo record, “Boyz”: a hip-pop, chart-designed paean to “bad boys” partly inspired by the dissolution of her most recent relationship, with actor Sean Sagar. The track is built around a sample of Diddy’s “Bad Boy for Life” (he cameos in its throwback-styled video, too) and features Nicki Minaj, whom Nelson previously worked with on Little Mix’s “Woman Like Me.” (Minaj’s verse was recorded before the infamous tweet about her cousin’s friend’s testicles; her part of the video, however, was recorded shortly after.) Making the song was something of a light-bulb moment for the newly solo singer early on: “I wrote it and realized, If there was a song out there to describe Jesy Nelson, this is it.”

Nelson, understandably, wants to now speak openly and often about all this newfound “control over [her] life.” So much of her career up until this point was tarnished by the incessant bullying and body-shaming she received from online trolls while part of the group, and how that, in turn, compromised the way she saw herself within its framework. Nelson’s breaks from the public eye are well-documented. In 2013, having already spent two years in the Twitter firing line (she would, she has admitted, search the phrases “Jesy Nelson fat” and “Jesy Nelson ugly” on there), she attempted suicide. Her moving and warmly received 2019 BBC documentary, Odd One Out, follows her through recovery. She has since left Twitter.

The day you announced you had left the group — can you remember where you were at that moment? How did that feel?

I was at home and hadn’t left my house for two weeks. I was numb. I’d just come out of hospital and was really sad. I was with my mum, and my family and friends were around me quite a lot. I didn’t really leave my bedroom, to be honest. It was a roller coaster of emotions. Then, obviously, I had to announce I was leaving, which I was fucking terrified for. I turned off my comments when I put that post up.

Why?

I’ve seen previous band members leave, and the shit they got for it: Zayn in One Direction, Robbie [Williams] in Take That, Camila [Cabello] when she left Fifth Harmony, when Geri left the Spice Girls. You’re always the baddie if you’re the first person to go. I was just thinking no one would get why I left. But my sister told me to turn them on because people were being so nice about it. I turned them on and I cried.

There’s been less than a year between you leaving Little Mix and you dropping your debut solo single, and the environment of the industry remains much the same in terms of public pressure and scrutiny. How do you know that you’re ready to do this?

I never left the group being like, I’m coming out of the industry now, I can’t deal with the spotlight. I couldn’t deal with being in a girl band. That’s what was mentally fucking me up. Constantly getting compared 24/7; that’s what I struggled with. That, paired with not having control over my life. It was like I was a robot with no feelings. It was like I was disregarded as a human being.

Until you’ve experienced being in that position, no one can ever say anything. It’s one of the hardest fucking things I’ve ever experienced in my life. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve had the most incredible memories, and I wouldn’t have this platform to be able to go solo if I wasn’t in Little Mix. I love music. That’s what makes me happy, so if I need to give that up completely, I’d just be stupid.

I know I’m ready, because since I’ve come out of the band it’s the happiest I’ve ever been in my entire life. I can genuinely say that. Of course, I’m going to have days when I struggle. That’s normal. But what I do know is that I’ll never go back to feeling how I did in the group.

The X Factor was the root of the trolling for you. How do you feel about the show ending after 17 years?

I’m never going to sit there and slate The X Factor because it’s given me the biggest platform, but I do think it has had its time. They weren’t the best with their duty of care for people. It ended when it needed to. It’s done all it can.

Do you think pop stars should have to be stoic and put on a brave face?

I think if you’re struggling, you should be honest about it and take a break. The show must go on? Fuck that! I think it’s bullshit, because all you’re going to do is mentally fuck yourself up even more, and I’m living proof of that. I tried to do that for ten years and look where it got me: I tried to [attempt] suicide. It’s not the way forward.

What is your relationship like with social media now?

I’m hardly ever on it, which I love. I’m a lot more private. I only really go on it if I need to post something or if I want to talk to my fans. I’ve become really close to so many of them. They confide in me a lot when they’re struggling.

You have direct conversations with them?

All the time. Some new, but some of the fans I speak to I’ve known for years. They’re just so sweet and so kind. They’ve got me through some of my darkest times, so I know I owe them a lot. To check in on them after what they’ve done for me.

Does your team have access to your social media?

They do, but I mostly post myself. I know me, and if I’m not in a good headspace, [social media is] gonna trigger that. I’m a self-destructive person.

What do you fear the most?

I know that it’s not going to happen … [but] probably falling back into how I used to feel a few years ago. But I don’t feel like that could ever happen. I really, really don’t. I know the people I’ve got around me now.

Do you feel protected now?

Yeah.

In terms of creative control, you also say you A&Red your own record before you even met your current major label, Polydor. What’s the mood board like for it, sonically and visually?

If you were to bring 1990s- and 2000s-era R&B and pop back and make it now, that’s what it sounds like. I went through a breakup when I was writing it; it was the first time I’d ever been heartbroken in my life. I cried for a month in the studio. I wouldn’t change it because I wrote the best fucking album from it, but Jesus Christ, I never want to experience that again. A lot of it [is also about] what I was going through in the band and how I was feeling. Then there’s just some bangers!

Prior to getting her on your debut single, had you gotten to know Nicki from working together in the past?

We performed with her at the EMAs, and I loved her from there. She’s so real, and I’m big on that. It’s weird to find that in this industry. And she’s the best. I thought, There’s no one more perfect for this song. I screamed when I heard [her verse]! I always knew I wanted her on it, because she’s the queen. I just love her so much.

Given this is such a big moment for you and you will want things to go well, does the backlash to her vaccine hesitancy make you anxious about having her on your song?

Not at all. Everyone’s entitled to their own opinion. If Nicki feels like she hasn’t done her full research and she wants to know more about the vaccination, then that’s her opinion. She’s there to be on my song, to do her part. She’s literally made my song even better. That’s nothing to do with my song and what we’re doing together.

Regaining control as a solo artist now streamlines the onus placed on her that could have once been shared four ways. Nelson is now the sole occupier of the spotlight, gearing up for her first single release with none of the original Little Mix women for immediate support. She seems confident that this will be fine, having removed herself from any discourse that could potentially eat her alive. Except this also means she’s filtered out the continued valid concerns and further criticisms from Black audiences who say she’s Blackfishing, disingenuously using the aesthetics of Black women and R&B to introduce her solo era in ways that don’t seem to have dawned on Nelson yet as capable of causing any harm. (In “Boyz,” she sing-talks, arguably in a Blaccent, “So hood, so good, so damn taboo / Know you know how to please me.”)

There’s a striking sense that Nelson views social media as a source of emotional burden, the very thing that drove her to attempt to take her life eight years ago; now, when any backlash arises from that source, especially directly related to her public presentation, that line between malicious trolling and fair criticism seems to blur and erode internally. In conversation and company, she’s affable and confident, attentive with an unwaveringly upbeat tone of delivery, even when she’s describing a somber or tumultuous event. It feels genuine — she’s likable and seemingly well-intentioned enough — but also like a protective barrier, the product of a decade in the spotlight as part of a band the British tabloids loved to use for fodder. Perhaps having spent half of that era shielding herself from the internet for her own protection has left her vulnerable to self-sabotage.

Standing solo now, what’s the mood?

Good nerves. It’s not like, This might fall to shit because — touch wood — even if it did, I know I’ve been true to myself. I’ve been so honest on the songs. I’ve been through the toughest breakup and told all the stories I wanted to tell. If it did go wrong, I’m okay with that.

[After leaving Little Mix], I remember being terrified thinking about what I wanted to do. My mum was like, “Why don’t we move to Cornwall and get a tea shop?” and I was like, “Mum, I don’t think that’s realistic!” Then I thought maybe I’d do more documentaries or go into TV, but then I kept coming back to music. Performing was my thing, so to not do that again saddened me. I couldn’t let that experience [in the group] take that away from me.

There’s been a notable shift in the way you were marketed then to the way you’re marketing yourself now, as an R&B-first pop star. In response, you’ve been accused of Blackfishing, allegations that when presented to you by The Guardian in August, you seemed surprised by. On reflection, do you understand the points being made?

The whole time I was in Little Mix I never got any of that. And then I came out of [the band] and people all of a sudden were saying it. I wasn’t on social media around that time, so I let my team [deal with it], because that was when I’d just left. But I mean, like, I love Black culture. I love Black music. That’s all I know; it’s what I grew up on.

I’m very aware that I’m a white British woman; I’ve never said that I wasn’t.

Some, many of them people of color, have said that when they’ve called you out for Blackfishing in the comments of your Instagram, they’ve been blocked by your account as a result.

I don’t know about that. Maybe it was my team.

Do you feel like you’ve changed the way you act or dress?

No, not at all. I’m just 100 percent being myself. If you look at me on X Factor with my big curly hair, I was wearing trainers and combats — that’s who I am as an artist and as Jesy. Now I’m out of Little Mix, I’ve gone back to being who I am. Like I said, I don’t ever want to be an artist who’s being told what to wear or what music to make. I want to be authentic and true to myself, and if people don’t like that, don’t be my fan. Don’t be a part of my journey.

Editor’s note: Following the interview, Nelson’s publicist confirmed that those comments had been deleted and users blocked by her management. In an email, Nelson said the following:

“I know comments relating to this had previously been deleted from my IG account, I only found out afterwards that a member of my management team had deleted comments. I’ve spent years being bullied online, so I limit the amount I go on socials. My management team have access to my account & they were trying to protect me & my mental health.”

Nelson canceled two scheduled follow-up calls to discuss Blackfishing and identity in greater detail. Instead, her publicist sent over the following statement on her behalf:

“I take all those comments made seriously. I would never intentionally do anything to make myself look racially ambiguous, so that’s why I was initially shocked that the term was directed at me.”

Do you think you have the power to control whether or not people see you as a role model?

No, I don’t. I think it’s amazing if people do, because I’m just being myself, and if you want to call me a role model, that’s amazing. I’m still learning, and I’m gonna make mistakes and go through shit. That’s just part of being a human being.

Do you feel less self-conscious now about your celebrity?

I used to hate it. I couldn’t ever go out.

What changed that?

Definitely getting older. I’ve got more confident with age. Doing my documentary, too. I’ve openly spoken about my struggles — even just getting that off my chest has made me more confident. I don’t feel like I’m hiding something anymore. That helped me with my anxiety.

And also just doing me. [In the past,] I wasn’t really true to myself. I didn’t really dress how I wanted to dress; I was making my stylist put me in corsets that I couldn’t breathe in for most of the day. I’d bruised my ribs trying to make myself look skinny. Now, I just live in tracksuits and baggy clothes because that’s what I’ve always wanted to wear. I’ve gone back to how I used to be before The X Factor. That feels really good.

Ideally, how do you want people to think of you?

I’d like people to say she’s very honest. She’s ballsy. Her music’s fucking brilliant. And she’s really come into her own as a solo artist. That this is the true Jesy Nelson.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.