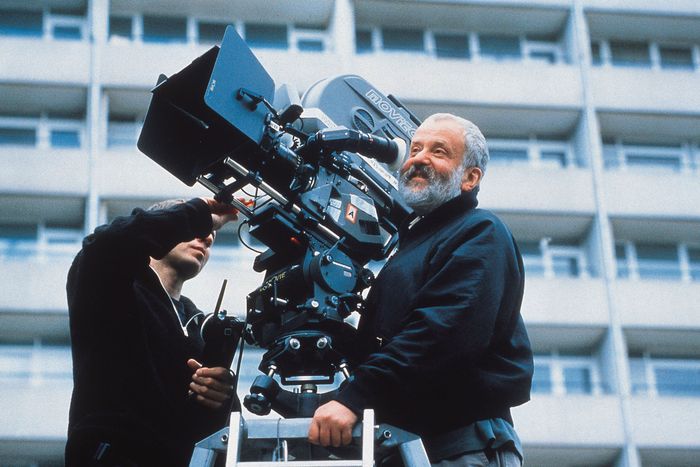

Mike Leigh doesn’t have a new film out, but this is a good time to be a Mike Leigh fan. For starters, one of his greatest and most underrated films, 2002’s All or Nothing, starring Timothy Spall and Lesley Manville (and a couple of fresh-faced actors at the time named Sally Hawkins and James Corden), has finally been released on Blu-ray, ahead of its 20th anniversary. In addition to that, 1993’s monumental Naked, which many of us feel is his masterpiece, has been restored and rereleased in the U.K. Simultaneously, there has been a major retrospective of Leigh’s work at the BFI in London, incorporating both his 50-year feature-filmmaking career as well as his enormously influential (and popular) TV work of the 1970s and 1980s. In the U.S., many of Leigh’s most important films — including his run of critically acclaimed features from 1983’s Meantime through to 1999’s Topsy-Turvy (a period which includes Naked and the Oscar-nominated Secrets & Lies) — are streaming on the Criterion Channel (and are available on Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection).

Leigh is a fascinating figure in world cinema, in part because of his unique process of creating his films, which doesn’t involve a traditional script (even though he’s been nominated for a Best Screenplay Oscar five times). Instead, Leigh starts off with ideas or concepts, then finds his actors — many of whom, like Spall and Manville and Jim Broadbent, he’s collaborated with for years — and then builds characters through intense, lengthy periods of research and improvisation, during which the stories begin to emerge. During rehearsals, the actors are often not told what the actual narrative will be, so they’re taken by surprise when any plot points present themselves. (Somewhat famously, the actors playing the family in Vera Drake did not know that the title character, played by Imelda Staunton, was a back-alley abortionist until actors playing the police came knocking at their door.)

Leigh developed this process in the 1960s and has stuck to it since, fiercely protecting his independence and artistic integrity. In this broad-ranging interview, we talked about all of these aforementioned films — in particular All or Nothing, Naked, and Vera Drake — the origins and nuances of his approach to filmmaking, and how he’s still steamed about that time the New York Film Festival rejected Peterloo.

All or Nothing is one of your greatest films, but I gather at the time that the reaction to it was fairly muted.

Yes, it was. I don’t really understand why. For anyone that was open to it or isn’t putting up barriers or prejudices, if it doesn’t get through to you on an emotional level, well then, forget it. It may be that it followed on from Topsy-Turvy. I thought, having done that previous, chocolate-box period film, so to speak, let’s go back to basics and look at issues that working-class people struggle with — the struggle on various levels, socially and economically, to survive. And some people, not everybody, used words like “miserabilist.” The trouble is, as we know, particularly people who earn their crust writing media, become obsessed with media. They see everything through a media lens or a media spectrum, as opposed to looking at it in terms of real life, which is the only way to read or respond to this film.

Timothy Spall’s performance might be the most heartbreaking one he has ever given. How did you and he work on that character?

I think it is the most heartfelt, and … I don’t know how to say this, but sort of as truthful of a performance as he gives in any of my films. Not that the others are not truthful, but he really taps into something very profound and understated. I can’t say very much about how we put the character together. I collaborated with him like I do with all the actors I work with, and we draw from real sources, real people, and create a character.

All or Nothing also marks the early appearance of two young actors who eventually became quite famous. You worked with Sally Hawkins on subsequent films. But there’s also a young James Corden.

James Corden now rules the world, so that’s in a class by itself. [Laughs] But they came through the ordinary processes of a casting director suggesting I see people. I saw a lot of young actors at that time. Sally Hawkins was one of them. Sally Hawkins is a consummate character actor. And when I say “character actor” — one of the things that’s important about the work that I do is it is about character actors, people who don’t play themselves.

But also, it’s interesting too, because talking about the cast of this film — The Tragedy of Macbeth has just come on the scene. I don’t know whether you’ve seen it yet. But the witch is played by Kathryn Hunter, who in All or Nothing plays the posh French lady in the back of the taxi. She was a distinguished experimental actress in Peter Brook’s company and very reluctant to do films. She said, “I don’t like films.” I persuaded her to do it. And of course, she’s fantastic as that woman in the back of the taxi. It’s only one sequence, but boy, does she deliver. It was all filmed in the back of a vehicle, driving around London, and through the Blackwall Tunnel and all that. It’s interesting to see her doing this very extraordinary performance as the one witch in The Tragedy of Macbeth. A great interpretation.

Are you ever concerned when you’re working with someone younger or less experienced that they might not have the patience and discipline to go through with your process?

I used to have more of a problem with older actors, who suffered the cobwebs of old-fashioned ways of working. That’s less of an issue these days, because as we’ve all got older, the once-young actors who could do experimental things have got older. And, in fact, I have worked with some very, very old actors, who have taken to my ways of working like ducks to water. I mean, in Topsy-Turvy, W. S. Gilbert’s father is played by an actor who is no longer with us, called Charles Simon, who was 89 when he did it. And he just was brilliant at the improvising.

How do you determine whether an actor can handle this process?

I do elaborate, long audition procedures. I only ever audition people alone. I initially get them in and just talk to them, have a conversation for a while, and if I think it’s worth pursuing, I bring them back for an hour or so each, and they do a bit of work about being a real person.

The housing-estate location for All or Nothing played a big role in how you were able to film it, as I understand.

People say my films are about characters, and they are, but they’re about place and environment, always. And because we develop the action always in the location, it’s an organic and integrated process. Once the story for All or Nothing had evolved in rehearsal time, I said, “Well, we’re going to need a housing estate.” And the response from my production designer and location scout was, “It’s very hard, filming in housing estates. People don’t cooperate.” We looked around and said, “Well, we might have to go really some distance away.” Then one day, they ran in and said, “Oh, you’ll never guess what. But just down the road, there’s a housing estate that’s empty because it’s going to be demolished, and the council have moved everybody out. And we can do whatever we like with it.” This social-housing estate, which had 300 apartments in it, was fantastic.

Vera Drake comes after this. Were you already thinking about the ideas behind Vera Drake? Because abortion is an element in All or Nothing as well.

I had the idea for a film about a backstreet abortionist on the go for about 40 years. I’m old enough to remember what it was like before the 1967 Abortion Act in the U.K. when people had unwanted pregnancies, and these women were the solution. I was aware of it from an early age, partly because my dad was a doctor in Manchester. Not that he performed abortions, because he didn’t, but I remember a private nurse who would help people and then would disappear from time to time. Later, I found out it’s because she had been in prison.

I’ve got as big a soft spot for Vera Drake as any of my films, really. The central performance in Vera Drake, Imelda Staunton — she is now playing the queen in The Crown. She’s a consummate character actor.

Vera Drake had that personal connection, but have you ever thought about making a film that was more autobiographical?

There are elements of autobiography sneaking through my films. I grew up in a provincial, suburban place. A part of my very early life was in an industrial area. I was born in the war, in 1943, so I was a child in the 1940s. I was a repressed teenager in the 1950s in the decade when we all lived in this Catcher in the Rye, squeaky-clean, respectable world, and “the done thing” and all of that, because our folks had actually been to hell and back in World War II. Though we only realized that later. And so, of course, we all escaped and let our hair down, literally, in the 1960s. Elements of those experiences lurk about in my films in all kinds of ways. But I’ve never wanted to make a film where one of the characters was me, as it were.

Given the fact that you don’t start off with a script, are you ever afraid that you might start your process on a project and wind up not being able to make a film out of it?

It has happened a couple of times. But on both occasions, it happened for external reasons, which I won’t go into, that had nothing to do with the actual form or content or the abilities of everybody involved. The conditions are very clear: I won’t embark on a project if there’s the remotest possibility that anybody is going to interfere, or want to know what it is, or suggest it has got the wrong ending, or recast stars and all that stuff. We have to be left to do what artists do, what novelists do and painters do, and poets and sculptors and musicians do — which is to go into their space and explore, and discover what the piece is by interacting with the material and arriving at it.

As I gather, the idea for your process actually came to you in a life-drawing class?

Well, that’s a bit of a reductionist myth. But it is true that in a life-drawing class, I simply thought, What we’re doing here is being creative, which is something we never did as drama students at the Royal Academy. Which I thought was dead, old-fashioned. I’d been trained as an actor. I went to two art schools, and I also went to the London Film School. Those things all contributed to my clarifying what I wanted to do and how I should go about it.

Was there a point, though, when you first realized, Yes, the way I’ve decided to go about this is going to work?

I started to try it in 1965 in what was called the Midlands Art Centre in Birmingham, where I got a job as an assistant director. For various reasons, they had a very impressive, state-of-the-art studio theater, but they hadn’t got actors. But they had got a so-called arts club for 16- to 25-year-olds. I was hired to do whatever I wanted with these young people. I had these ideas about trying this sort of thing. Soon as we did it, we thought, Okay, this works.

I knew I wanted to make movies. I just had been to the London Film School, and I’d been in a couple of films. And I’d made some shorts. But throughout the ’60s, it was all theatrical experience until such time as we could make a movie. And that was Bleak Moments, which we made exactly 50 years ago. There’s a new restoration that’s been done by the British Film Institute, and it’s going to be in the Criterion Collection, as is a new restoration of Naked, which is going on theatrical release in the U.K.

There has been a retrospective of all your work recently in London, at the National Film Theatre at the BFI. Do you ever rewatch your films?

Yes. I do. I mean, I’m not like Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard. I don’t watch them every night! But do watch my films. I like my films. And it’s a privilege because I know a lot of directors, when you ask, “Do you ever watch it?” they say, “I can’t bear it. I can’t look at it.” And the reason is that they hate the finished product, because it’s not the film they wanted to make. They had to cast it in a different way, they had to recut it, they had to change the composer, they had to alter the end, and the thing was screwed up by any number of interfering busybodies, and they feel very disconnected from it. I am extremely lucky that has never happened, so I have a fond, parental relationship with all my films. Some more than others.

I saw Naked in college, which is probably the exact right time for a movie like that. So for me, it’ll always be your greatest film. But it’s fascinating to revisit, because it changes with every viewing. Since Naked is being rereleased, have you noticed any changes with the way people respond to it?

Broadly speaking, the audience responses to Naked have been good and consistent. The only real difference is that when it first appeared, certainly in the U.K., there was a small but vocal objection to it as being misogynist from some militant feminists. That reaction to the film has disappeared, I’m glad to say, because it’s an unsophisticated and naïve reaction to the film and a misreading of it. There is unquestionably a profoundly misogynist character in the landlord. But Johnny is more complex than that. And the film is about so many things that it leaves you, I hope, with a great deal to go away and ponder.

But in a way, that’s what I feel about all my films, including All or Nothing. They’re not message films. They’re not films that say, “Think this.” I mean, they leave you with stuff to argue about, if you like.

Is that harder to do today? Some people say that it’s harder now to make or show films that don’t have specific messages, or clearly defined good and bad characters.

Well, we have to be clear as to which film culture we’re talking about. You are on the other side of the Atlantic, which means that there’s a possibility that you’re talking about people whose terms of reference are defined by Hollywood. Now, I personally regard what I do as being part of that other major operation, which is what we call world cinema. Which is all kinds of stuff made by all kinds of people, much of it about the way people live, and not interfered with and compromised in the way that often Hollywood movies are. I’m not saying that all films that are made in the United States are Hollywood films; I know that’s not true. And certainly, it’s tougher to get backing for films at the moment.

Getting back to Naked, what was the initial idea that you worked from with that film?

We made it in 1992. I was beginning to be aware of something that people weren’t really talking about, which was the impending millennium. I also wanted to make a film about male behavior. These are kind of conceptual possible starting points rather than actual fixed ideas or agendas or objectives. Because I’d just made High Hopes, followed by Life Is Sweet, which was kind of a domestic film. I wanted to break away from that.

When you first started, did you know that it would be primarily about David Thewlis’s character, following him around?

Yes, yes. He had been in a couple of things I’d done, and he was in Life Is Sweet. But his part in Life Is Sweet, because of the dramatic requirements of his character, was brief. He understood that, but he wasn’t pleased about it. So, I approached him and said, “Did you want to talk about doing another film?” He said, “Look, the thing is, I appreciate it, I’m not complaining about Life Is Sweet, but how do I know the same thing won’t happen again?” So I said to him, “I guarantee that whatever happens, you’ll have a substantial portion of the pie.” I think you could say I stuck to my promise.

Did he discover the subjects of all those monologues and rants himself?

As always, we collaborated on the character. But all the actors do a lot of research, whatever it may be. Spall drove around in a taxi [for All or Nothing]. Marianne Jean-Baptiste learnt how to be an optometrist for Secrets & Lies. Claire Skinner, who plays the plumber twin in Life Is Sweet, to this day people she knows phone her up and say, “My toilet is leaking. What shall I do about it?” David is a very intelligent and well-read actor. But one day, I called him to a rehearsal at four o’clock, and he came in and said, “I’ve just met this mad American in Soho who has got all this stuff.” And he’s pouring out all this bullshit about laser tattoos and 666 and all that stuff. We sort of distilled that. Johnny is a repository of all kinds of stuff, some of which he churns out ironically or for the naughtiness of it, rather than because he’s a religious nutter or anything, which he isn’t. I mean, on one level, as far as I’m concerned, the portrait of Johnny is a statement about an inadequate educational system.

For many years in the U.K., you were known primarily for Abigail’s Party. Is that still the case? I love Abigail’s Party, but in the U.S., almost nobody knows what the hell that is.

Here’s the thing. Abigail’s Party is a stage play, which we wheeled into an old-fashioned, five-camera television studio … a terrible medium. If you look at Abigail’s Party, you’ll see boom shadows and inconsistent lighting and all of that. But we did it after the actors had performed it 104 times in the theater, so it was rock-solid. It was screened on BBC Television, and the third time it was screened was on a very, very stormy night throughout the British Isles. It was on Channel One. There were only three channels at that time. On Channel Two, there was a very highbrow, intellectual program that nobody wanted to watch. And on the commercial channel, there was an industrial strike. So, 16 million people tuned in to Abigail’s Party, and it became a cause célèbre.

So, you never know what’s going to become iconic and what’s going to sink without a trace. I think one film we haven’t talked about, which is very important, is Meantime. And, thank goodness, that is in the Criterion Collection.

Meantime had quite a big impact over the years, even when it was very hard to find, right?

That’s exactly the case. We wanted to make it as a feature, but it was a Channel 4 film. And it was the third Channel 4 film. It was very early, and they hadn’t quite got it together to back 35-mm. cinema films. So it was a telefilm, and it did sink without trace. But for years, I got letters from people saying, “I’m unemployed. I’ve seen Meantime,” or “I’ve got a pirate copy of it which recorded off-air, and it has changed my life,” or “It’s a lifesaver.” It was about unemployment at a time when that was a real issue. It still is, of course. So it did resonate. And of course, apart from anything else, it had two little-known actors called Gary Oldman and Tim Roth in it! And Alfred Molina and Marion Bailey.

Meantime is quite a subtle film. The subjects of youth unemployment and skinheads and domestic strife and mental disability — it could have been very melodramatic, hard-hitting. But in terms of what happens, it’s not a particularly shocking movie. We just get a sense of life going on in all its despair and complexity and open-endedness.

I mean, on three occasions when it came out, one in London, one in Wales, and one in Sydney, Australia, I attended screenings with a question-and-answer session. On all three of those occasions, guys stood up from the far left and criticized it aggressively for being a wasted opportunity. Basically, their concern was that you don’t see people manning the barricades in the film. It doesn’t make a revolutionary statement. Now, that’s open to some debate, depending on what you’d call a revolutionary statement. As far as I’m concerned, it absolutely deals with the issues. But it does it through what happens, looked at intimately between these people in this extended family. None of my films leave you with a black-and-white message.

Godard used to say that the point was not to make political films but to make films politically. I feel like in many ways, your whole process is fundamentally a political process, because it’s about getting into people’s worlds and understanding the lives of people who you might not know. That seems to me an incredibly political thing for an artist to do.

Well, I agree.

This period in the ’70s when you were working in television is a fascinating time. The world wasn’t aware, but there was a full-fledged renaissance occurring, with you and people like Ken Loach and Alan Clarke and Dennis Potter doing all this incredible work for the BBC.

We used to say around the BBC that the world out there thinks there is no filmmaking in the U.K., but in fact, it was very, very vibrant and alive and, well, just hiding in television. The great thing about the BBC at that time — and I stress that, as opposed to at this time — was the freedom. “Okay, there’s the budget. Those are the dates. Go away and make a film.” It was fantastic.

To some extent, the British film industry at that time was still an outreach of Hollywood. You couldn’t get an indigenous, serious, independent British movie together. Occasionally, things slipped through the net, but very few and far between. We used to say, “Why can’t we make these films on 35, put them out in the theaters and the cinemas, give them a theatrical release, and release them worldwide out there, send them to festivals, and then show them on telly?” And the BBC used to say, “No.” But the guys that started Channel 4, Jeremy Isaacs from the BBC and David Rose, who was a BBC producer, were listening. Channel 4, once it got going, changed the landscape.

We made my first film independently, Bleak Moments, in 1971. And if you had told me at that time that I wouldn’t make another feature film until 1988, with High Hopes, I’d have jumped off Waterloo Bridge. It was unthinkable to me. But that’s what happened. Once we all started to have the opportunity to do movies because of Channel 4, it took off. And the rest is history.

Over the years, has there been a film of yours that you wished people had appreciated a bit better or that you thought was misunderstood?

Yeah. It’s called All or Nothing, and we’ve talked about that already! To some extent, the reaction to Peterloo was disappointing. Two things happened. One is that it was not accepted by Cannes, which we were very surprised and shocked about. But not as shocked or surprised, and indeed angry, as we were by the fact that it was not accepted by the New York Film Festival. That really pissed me off! I mean, Cannes is different. Cannes, they have to pick the competition; they’ve got their own idiosyncratic, Parisian criteria. And we did quite well in Toronto and all that. But there is no excuse for the New York Film Festival.

And when I came to New York subsequently to do press, all your comrades, serious film journalists in New York, were equally outraged by the fact. I love the New York Film Festival because of the fact that it always happens at a very nice time in the year in New York, so it’s a very good atmosphere. It’s the most intelligent audience in the world. The question-and-answer sessions are to die for. And it should have been there. Peterloo wasn’t released in France or Germany. Nobody took it, which was very disappointing because my films have been successful consistently in both of those territories. The same thing happened elsewhere. It may be that it’s not everyone’s cup of tea or not everybody is interested in what happened at that period, but since the film is not parochially just about what happened in Manchester in 1819, but it is about democracy and it’s increasingly relevant to us, you might have thought it would have a wider resonance than it had.

Did a similar thing happen with the French and Topsy-Turvy?

Sometimes, these things are to do with particular people who have particular bees in their bonnet. French backers wouldn’t let us take Topsy-Turvy to Cannes. They said, rather extraordinarily, “The critics will eat you alive.” We thought we’d made a rather brilliant film, and in fact it went to Venice and Jim Broadbent won for Best Actor. Cannes turned down Vera Drake as well, which was really shocking. And we sent that to Venice and we won the two top prizes.

The French backers of Secrets & Lies, Ciby 2000, liked the film, but they thought there were scenes in it that we should definitely cut. There’s the scene where you see Hortense, Marianne Jean-Baptiste, in her apartment with her Black girlfriend, two Black women, chewing the fat. And the scene where the guy that used to own the photographic studio comes back in a terrible state. Now, those two scenes are fundamental. But they simply said, “No, you have to cut them.” There was an incredible standoff, and they did a Hollywood-type test screening at Slough, outside London, in a 300-seater cinema showing the work print. A complete waste of money. The standoff went on for months, and finally they decided to screen it during the film market week in London for all the distributors, in the hope that people would say, “Cut those scenes.” And all the distributors, including unlikely people from Warner and Disney, they all said, “It’s perfect. Don’t touch it.” So they finally relented, and we went to Cannes and won the Palme d’Or and the Best Actress for Brenda Blethyn. And they left with their tail between their legs. So, this is the kind of bullshit that we have to put up with.