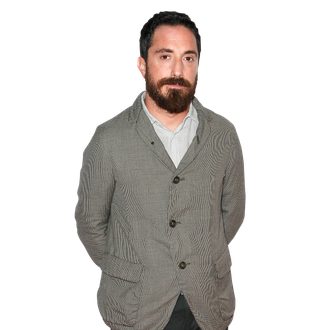

Spencer director Pablo Larrain is joining us at Vulture Festival to literally put on a film school for us. Join us at the Hollywood Roosevelt in Los Angeles on Sunday November 14 at 11:30am to learn about the five films that have shaped the filmmakers’ approach to his craft. Get your tickets here!

You never know where Pablo Larraín is going next. After making several films in his native Chile, the director gave the biopic genre a much-needed jolt with Jackie and Neruda. The thrillingly unorthodox films, both released in 2016, reinterpreted their subjects’ public images, zeroing in on singular chapters of Jacqueline Kennedy’s and poet Pablo Neruda’s lives to subvert the cradle-to-grave approach that most filmmakers take. This fall, Larraín will release the much-anticipated Spencer, in which Kristen Stewart plays Princess Diana. The film follows her over the course of the 1991 Christmas holiday when she decides to leave Charles. If the haunting close-ups in Jackie and the noirish lyricism of Neruda are any indication, Spencer will be another mood-driven interpretation of its subject (including a score by Phantom Thread’s Jonny Greenwood and cinematography by Portrait of a Lady on Fire’s Claire Mathon). Larraín sees biopics not as historical documents but as fables that can reveal profound insights about human nature.

In the run-up to Spencer, however, Larrain released a non-biopic work — the low-budget DIY odyssey, Ema, now playing in select theaters. Set in his home country, the movie follows a testy choreographer (Gael García Bernal) and a pyromaniacal dancer (Mariana Di Girólamo) who recently gave up the child they’d adopted together and are in the throes of relationship chaos. Larraín, a master of cinematic reinvention, gave his Ema actors only a broad outline to start with. Once production began, he handed them the script pages (developed with writers Guillermo Calderón and Alejandro Moreno) the day before those scenes were to be shot. Along the way, the cast and crew would feel their way through the volcanic story, often taking inspiration from the trippy lighting design and the reggaeton-inflected score. “It’s very different from everything else I’ve ever done, so I keep it in my heart with a lot of love and good memories of the process,” Larraín explains in an interview with Vulture, in which he discusses hiding scripts from his actors, the Hollywood projects he’s been offered, and the moviegoers who will inevitably misunderstand Spencer.

It’s interesting that you chose Ema after Jackie, a movie that was very demanding in terms of production design and your obligation to historical accuracy. You’d re-created an entire White House tour shot for shot. Ema let you go in any direction you wanted. You didn’t even let the actors see full scripts. After Jackie, were you looking for something more stripped-down and open-ended?

It’s not really a reaction to a previous work. It’s basically, Where are the possibilities to find the space where you can be as free as possible? What I really try to do is challenge the conventions of “how do you make a movie?” A movie is made with a lot of people, and a movie is made with — as you were saying — preconceptions of whatever you’re going to capture. The bigger the movie, the little that is left for [what happens on] set. There’s a way to do the opposite, which is to really not prepare anything and just have a script that is in development as you shoot. That’s what happened with Ema and another movie I did, The Club. They were both made with the same styles. Actors never knew the script; they never knew what we were going to shoot. They spent more time dancing than talking or rehearsing at all.

What was the structure of the film that you went in with compared to the final product that we now see?

We shot three different endings, and we had a very abstract structure that I think is reflected in the movie. But how things happened and how they evolved in the characters is all new. We started shooting with an outline, and then during the process, we were writing. It might sound crazy because movies are made the same way all over the world — you end up with an actor in front of a camera and things can be very simple somehow. But it’s a low-budget film and we didn’t really have to explain the movie to anyone. We didn’t have to go out and try to make a point and present a script and a schedule. No, we just found pieces over time and put them together.

You certainly wouldn’t have been able to make a movie that way in the United States. Were you specifically seeking the freedom that Chile gives you?

Yeah, it’s possible that this movie, in the way we did it, would never have been made anywhere else. But also this movie is made in the heart of a city that only exists [in Chile], so it could only happen there. The city [Valparaíso] is a character — that beautiful and strange port that we have on our coast is full of history and our own ways for immigrants. It has a very punk, artistic culture. I think the new movie Gaspar Noé shot, he did it like this. Maybe there are people who are trying to do this. Part of the problem is that it’s so expensive to shoot in the U.S. The system in the U.S. will never allow you to make a movie like this, even for a low budget. Here, we do have unions and you respect them, of course, but there’s a way where people can go and feel that they’re really expressing themselves on a movie and not just moving a light or putting a dolly somewhere. That creates a different energy in the crew and in the cast. They understand that it’s a little journey and it takes a couple of months to do it.

This is the third movie you’ve made with Gael, who has said that he signed on before reading any kind of script whatsoever. There must be a reason that you keep returning to him. What kind of shorthand developed at this point?

He’s a very good friend, first. We’re both parents, and I think there’s something in the subject that we cared about. Then there’s something in the character himself, which is the absurd crisis of the artist. I guess he connected with that, too. He’s obviously a great actor and a very handsome person, but he has something that is the essence of cinema, which is that he’s mysterious. You put him in front of a camera and you ask him not to do much and to just give a few indications, and the audience will always wonder what’s going on. It’s that mystery. Maybe people don’t go to the movies and say, “Hey, I love that actor because he’s mysterious,” and even sometimes in the press or in the reviews, they don’t talk about that. But if you talk about great actors, most of them have that. I’m always mesmerized by that.

Much of your work revolves around characters in crisis: the central couple in Ema, the protagonists in No, Jackie, Lisey’s Story. In Spencer, Diana is at Sandringham House, where the royal family spends its holidays, grappling with her disintegrating relationship with Charles. Why do you think you gravitate to that?

Isn’t it the key of cinema to have an actor or a character in a crisis? All the dramatic theory orbits around that somehow. There are movies like Jackie or Spencer where you don’t know what the character wants up until the point of the movie. Some characters don’t know what they want, but a situation makes them understand they are in a crisis. And as the movie evolves, they need to really understand it. So it’s a more existentialist type of cinema. It’s really about the structure, but there’s always something that has to make the character explode.

At this point, you’ve worked with a number of famous A-listers: Natalie Portman, Julianne Moore, Clive Owen, Kristen Stewart. As talented as they may be, audiences have preconceived notions of them. What’s the advantage of casting someone like Mariana Di Girólamo, whom audiences can see as a blank slate?

I actually just saw a picture of her in a magazine, and then I had a coffee with her and we hired her. She had some experience in television, but not a lot in movies. Gael was very helpful in understanding the logic of how you make a movie with a single camera and how you perform for one camera. But I guess the main thing is that Mariana, as the character, is completely unpredictable. You have no idea what’s going on inside of her, and that makes her quite dangerous, especially when she’s holding a flamethrower. I remember we were testing it, and we were going to have a stand-in who was going to operate the flamethrower. But Mariana wanted to do it. I said, “Mariana, that is not how you do movies. You’re going to have a stand-in. It’s a war weapon.” She really insisted. All of a sudden, I had an actress that I never knew really throwing a loaded flamethrower on the set. We rehearsed it and it was safe, but it was like, Whoa! She built that character from an unknown place. She didn’t know much about the character or the story because I hid the scripts from the actors.

If you hid the scripts from the actors, what did you tell them?

I told them the main concept and where it was going. Sometimes it was troubled.

Troubled?

Yeah, because some actors would take it well and say, Okay, whatever. But Gael, sometimes I would say, “Do this” or “Say that,” and he was like, Why? I’d say, “Because that is what’s needed.” “Okay, but I need to understand, my friend.” There are many ways to make a movie, but in this case, it’s an exercise in facing the void of life. You have no idea what’s really going to happen to you in the following hours; anything can happen. That’s what I was trying to reach. I wanted actors who were standing there in a void of things that may happen or may not.

The style of dance that we see in Ema makes so much sense in terms of the personalities of the two central characters. The choreography is full of sensual silhouettes, very street-dance-inflected. Tell me about conceptualizing the style of the choreography and what it represented for you.

I’m about to turn 45, so reggaeton is something that’s not really my generation. It’s quite strong in Latin America. [Composer] Nicolas Jaar made me think that the only way to do this was through reggaeton. We quickly changed the concept that we had before, which was more of a contemporary dance company, and we turned it into more of a street-type dance. We brought that into the argument of the film, because the choreographer [played by Bernal] does not understand the love and passion for reggaeton. And the dancers who really feel that they want to express themselves want to connect with what’s going on in the streets. They don’t care about this idea of “culture.” That was a very interesting friction. And then I had to embrace reggaeton. It was not easy! It’s a very tough, distinct melody that has roots in Central America, which, even though it’s close to us, is quite different from our culture. It made me understand that we were making a movie about a generation that is different from us.

Our country is changing right now in an incredible and great way because of the new generation. Dance opened my eyes to something that was way deeper that has political meanings and also a cultural perspective that I needed to embrace and understand. That was very beautiful for me. At some point, instead of conducting them so much, especially the female characters, I just let them say what they wanted. Somehow that became very relevant to the heart of the narrative.

Something I admire about your work is the way that each project is stylized in a totally different way. I think back to the film-noir stylings of Neruda, the extreme close-ups in Jackie. Do you feel like you get to reinvent yourself with every movie?

I try. I wouldn’t want to repeat myself. I admire a lot of directors who have a very precise style over the years, like Pedro Almodóvar. You know what you’re going to get when you see his movies. But I’m trying to behave in a way that I can feel surprised with the way that we’re shooting. I’m trying to look for something we haven’t done before and to be in a place that is unknown for [the audience]. You don’t always succeed, but I try to stay out of the comfort zone with things that you know will work.

I want to create a mood. For Ema, the mood and the tone of the film are part of the experience for the audience. In this case, having Nicolas’ score before we started shooting really helped me to understand how we were going to move around. What was the speed? What was the tone? Estefania Larrain, our production designer, designed everything with very precise colors, and Sergio Armstrong, our DP, went really weird with certain lighting systems. I hadn’t seen something like that, at least on my sets. Then you embrace it, and that becomes the style of the movie. It’s interesting when you try to do that because also I never see a movie again.

Your own movies, you mean?

Yeah, I just don’t look back, because it’s very cruel.

By the time Jackie came out, you’d been making movies for a while. But it really put you on the map with American audiences, and obviously people are going to draw comparisons between it and Spencer. What kind of offers and opportunities did you get from Hollywood in the wake of its success?

All kinds of things. I don’t think Hollywood executives could put me on any specific list around any specific type of movie or style. I remember when I started working with an agent at CAA nearly 14 or 15 years ago. I did a movie called Tony Manero that was about a serial killer, and then I got a lot of serial-killer scripts, which was strange. And then over the years I have been invited to different kinds of things. I worked for a while to develop Scarface, but it didn’t work out. When I was invited to do Lisey’s Story, I thought it was something interesting because it just came out of nowhere. There wasn’t really a logic for why you would be inviting someone like me to do something like that. I had never been in that space before, so I went for it. I love to be hard to classify.

Are you conscious of the fact that, after Jackie, Neruda, and Spencer, people see you as someone who is deconstructing the biopic genre?

I’ve never done it consciously. First, I don’t have a plan of doing this or that type of movie. I’m not trying to build my career so people can create any kind of logic or analyze it in any specific way. Also, I don’t think I’ve ever done a biopic. I think Neruda and Jackie and Spencer are movies about people in certain circumstances where everything is about to explode. They’re not really biographical analyzations; it’s not the study of a life of someone. I think some people could misunderstand it. Before they go to see a movie like Spencer, they might say, We’re going to really understand who this person was. No! Wrong number! Wrong movie! We don’t do that! We’re just trying to work with whatever that person was and create a fable out of it. That’s what I’m looking for. We’ll see if it works.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.