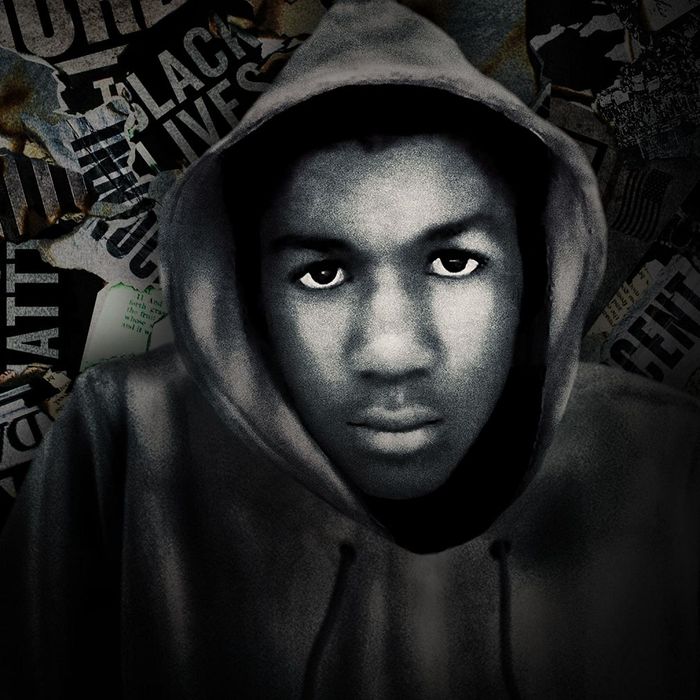

Maybe I am not in a good place. Maybe itÔÇÖs mood or hormones. Maybe itÔÇÖs pandemic life. Maybe IÔÇÖm too old, been Black in America for too long. Maybe IÔÇÖm simply too tired of all of it. Whatever the reason, I found it very hard to recently watch for the first time Rest in Power, the 2018 Jay-Z-produced documentary about the death of Trayvon Martin, the trial of George Zimmerman, and the aftermath. I skipped it then for the same reason a person who has survived a shark attack might skip Shark Week. Nonetheless, it remains the only legitimate documentary about Trayvon. Could it offer me something in the way of inspiration or a sense of validated identity from seeing this story told well? At first, all I thought it did was stir up the same feelings that havenÔÇÖt left me since TrayvonÔÇÖs killing: an angry fatigue, a charged boredom, a shockingly broad and fierce weariness at how much time we must spend convincing this country that our lives matter.

The six-part series ends audaciously hopeful. After five episodes meticulously detailing how a Black child was killed at the hands of a white Hispanic man known to be a virulent racist whose own neighbors admitted the only reason he noticed, approached, and harassed Trayvon was because Trayvon was Black; after five episodes detailing how ZimmermanÔÇÖs defense team successfully tried Trayvon for his own killing, claiming he had brought death upon himself by being a Black teenager in a world violently afraid of Black teenagers; after detailing how the judge refused the mention of race in her courtroom; after demonstrating how the mere presence of Zimmerman as a defendant in a court of law led to the election of Donald Trump and an unprecedented rise in white hate groups; and despite detailing how an entire media industry coalesced around villainizing Trayvon ÔÇö after all that, the documentary ends with rousing music and all the inspiration of a Pepsi commercial.

There is also an irony to hope. Hope is necessary to ward off despair, to foment resistance. Yet it is remarkably useful for keeping intact the systems that caused the despair. Hope tells you that weÔÇÖre almost there if we just keep going. It omits that if they wanted this to stop, it already would have.

Rest in Power was directed by Jenner Furst and Julia Willoughby Nason, whose previous credits include Time: The Kalief Browder Story. Their approach here is unassailable and not meant to change minds. If you believe Zimmerman innocent, youÔÇÖre probably not watching this doc in the first place. If you believe him guilty, youÔÇÖll find Furst and Nason are competent with this form. TrayvonÔÇÖs story is treated with respect, his narrative straightforward and uncomplicated: A child was wrongly killed. A system conspired to ensure there was no justice for his family. ThatÔÇÖs America. The series has a 100 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes and was nominated for an Emmy. Critics said it should be ÔÇ£required viewingÔÇØ and called it a ÔÇ£gut punch.ÔÇØ

I guess after years of gut punching, I am left wondering, What is the point?

Sometimes the quest for full humanity in America feels like chasing a mirage. It is something I occasionally have to talk myself into believing. ItÔÇÖs partly why projects like Rest in Power get made. They are an affirmation of hope, of which there has been an apparent deficit since TrayvonÔÇÖs killing. Media about Black political trauma ÔÇö from Ava DuVernayÔÇÖs history lesson 13th, to genre projects such as Antebellum and Lovecraft Country, to feel-good features like Hidden Figures and Green Book ÔÇö has exploded. While these works offer little in the way of material comfort to the afflicted, they do plenty to make the comfortable feel that by clicking onto our suffering, they have contributed something material to our liberation. Maybe the aim is to make so clear a case to anyone non-Black of how deeply broken this country is that they feel the fire in their bellies to make change.

This cycle of hope and despair has become its own content industry. Being angry at police is a content industry. Being angry at people who are angry at police is a content industry. There are enough corporations making money from all of it, no matter whoÔÇÖs the angry one or the right one, that itÔÇÖs difficult to believe that anyone invested in the mediaÔÇÖs survival would ever be pleased to see it stop.

IÔÇÖm also left wondering which audience Rest in Power wants things to click for. I figured it couldnÔÇÖt have been me. I resisted the documentary. I spent long sections of it looking at my phone, thinking about dinner, and texting with friends. I hated watching it. I hated it because it was good enough at its job to remind me that, like many Black Americans, I loved Trayvon Martin like family. I loved his parents and his friends and his brother. I wanted nothing more than to be with them, to eat food with them, to crack jokes, play cards, fill up the room with our laughter, roast one another late into the night. I wanted him to be here for all of that. I loved him because he died when he did not deserve to die. I loved him because he was hated in the exact same way I am hated and for the exact same reasons.

Like I said, I may not be in a good place.

At one point, the series includes news footage of Colin Kaepernick at the height of his anthem protest explaining why he knelt. ÔÇ£This country stands for freedom, liberty, justice for all,ÔÇØ he says, ÔÇ£and itÔÇÖs not happening for all right now.ÔÇØ I used to wonder why Kaepernick was the only athlete to pay a significant professional price for this political stance. Now I think it is because that anthem protest did more than honor a legacy like TrayvonÔÇÖs; it challenged a set of deeply held assumptions, chief among them that America itself is a place worth honoring. This is what angered people most. You can make noise about racism, you can make documentaries about the innocent and unarmed, you can publish essays in magazines, you can maybe even raise your fist on national television, and you will still get paid. But the one thing you cannot do is question whether this country is fundamentally deserving of our care and labor.

If thereÔÇÖs anyone this documentary is truly for, it is TrayvonÔÇÖs parents, co-producers on the series. They needed to see his humanity dignified, his story truthfully told. Furst and NasonÔÇÖs biggest directorial accomplishment was not to stand in the way of Tracy Martin and Sybrina FultonÔÇÖs vision.

The jumbled final episode focuses on the trialÔÇÖs aftermath. It tries to cover Dylann Roof, Charlottesville, Trump, the impact of the trial on the local police force, and the creation of Black Lives Matter. Author Mychal Denzel Smith talks in it about the phrase that became the slogan of a movement. ÔÇ£It was this rallying call that everyone could get behind that very clearly and plainly stated that Black lives indeed matter,ÔÇØ he recalls. ÔÇ£It may not matter to George Zimmerman, but they matter to us.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs a deceptively simple distinction and, for me, one of the only clarifying moments of the entire series. The more ÔÇ£Black lives matterÔÇØ became a chant in the streets, the more it took on the life of an outward-facing slogan. ItÔÇÖs as if we are chanting it to get others to understand. But Smith reminds us that the roots of our resistance and survival do not lie in convincing anyone else of anything, that the fight for legislative change remains as vital as it is because such change keeps more of us alive, and that there are people in power who still need repeated convincing that what happened to Trayvon should never happen again. Even as it does.

But ultimately, it increasingly feels to me that our liberation is not bound up in the law, the news stories, the pet projects of billionaires, or even the prestige docuseries ÔÇö it is bound up in the love and care we take with ourselves and one another. These days, we are the only power I can rest in. It just may be that many of us need a project like Rest in Power to remember that. I can live with that. I guess I have to.