A siegelike mindset ÔÇö unspeakably isolated, sleepwalking, wounded, monomaniacally self-enclosed, but finally atoning ÔÇö inhabits Robert GoberÔÇÖs exhibition at Matthew Marks Gallery. The showÔÇÖs title distills our self-cannibalizing and polarized time: ÔÇ£Shut up.ÔÇØ ÔÇ£No. You shut up.ÔÇØ The exhibition, which is open through January 29, is a portrayal of crisis and alienation that grants a concluding palliative grace. It isnÔÇÖt for everyone, and its stripped-down colorless minimalism and fussiness will probably have struck some as boring belly-button-gazing and the fetishization of trauma. But for me it was a very slow-burning, donÔÇÖt-miss show.

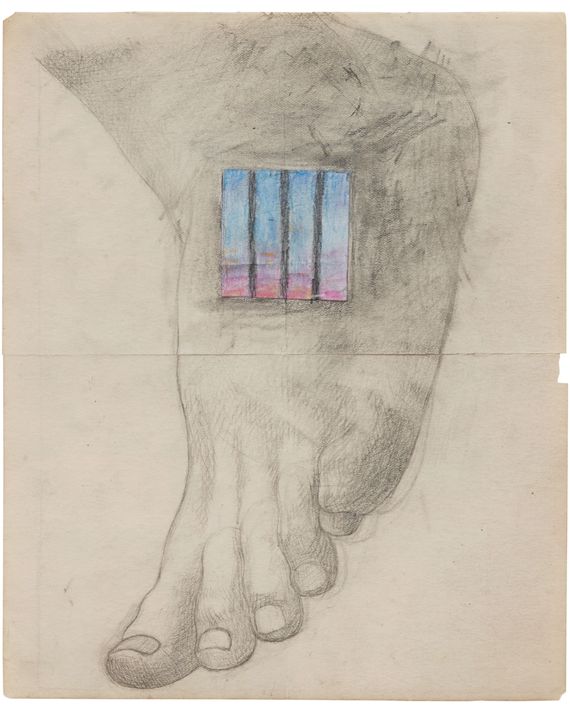

Laid out in five galleries are 22 works. There are 13 found academic pencil-drawings of feet to which Gober has added barred prison windows. Distributed throughout the show, these images form a kind of repeating visual choir ÔÇö aching, estranged. TheyÔÇÖre a poignant book of hours where time moves barely at all and under inner pressure. The barred windows made me think of ProustÔÇÖs observation, ÔÇ£ThereÔÇÖs no such thing as a beautiful prison.ÔÇØ

But the main works here are eight reliquary-like wall pieces, enclosed windows, haunted Wunderkammers filled with strange objects. While every object looks found, in fact everything youÔÇÖre seeing has been hyperhandcrafted by Gober and his assistants with a Shaker-like dedication. There are tubs of farm grease, a robinÔÇÖs nest with teeny blue eggs resting on top of a rusty muffler poking through a shade, half-drawn blinds, a tree trunk seemingly grown inside the house, cut out winter snowflakes Scotch-taped to greasy windows ÔÇö signs of children, home-schooling, Christmas, or empty nests. We see cigarette butts, packing peanuts, police-athletic-association decals. In these decals I saw the cracked visage of institutions disintegrating before our collective eyes. Each of these Joseph CornellÔÇôDonald JuddÔÇôlike repositories resembles the closed windows of American working-class homes. Time stops here or is in slow motion. These floating otherworldly tombstones seem to intone the Latin burial inscription, ÔÇ£What you are, I was; what I am, you will be.ÔÇØ

Together these windows anthropomorphized for me into American lives fortressed behind walls and glass. I projected the inhabitants as white families. I felt an atavism of the occupants inside, people who imagined themselves in danger, looked down on, humiliated, aggrieved, vengeful, feeding on fears of everything that is not them. Everything outside these windows is seen as a threat. I felt the crushing sadness of this last half-decade, and more since January 6, gazing helplessly at the extremism, cruelty, corruption, victimhood, fatalism, moral damage, and the infantile rebellion against all authority that has only frozen more solid. I saw how dark IÔÇÖve become about America. How every conversation with a stranger has an edge to it and the sight of a MAGA hat seems something like an American swastika to me. Meanwhile, I know that these people look at me the same way and see a patronizing elite trying to take their ÔÇ£freedomÔÇØ away.

An American Ur-window formed in my mind: The one I once contemplated through beat-up shades in Cushing, Maine, in the home that inspired Andrew WyethÔÇÖs iconic ChristinaÔÇÖs World. The house is still standing. I laid in the grass exactly where Wyeth placed Christina. In GoberÔÇÖs windows, Christina is America: Disabled, fallen, unaided, enigmatic, enervated, filled with longing, accursed, anointed; a fallen angel, lonesome dove, and failed state. In the reflections of GoberÔÇÖs closed windows I saw not only how we have all been traumatized by the events of the last years, but my own paranoia.

All this comes to a head on the back wall of the final gallery in a modern masterpiece. Titled Waterfall, it is a life-size figurative sculpture of a fragmented torso without arms, seen from behind, and outfitted in a wool-cotton suit jacket. A floating Magritte, mannequin, or ghost. An opening lets us peer inside. ItÔÇÖs strange entering another body this way in public, vulnerable, exposed, erotic, voyeuristic. Inside thereÔÇÖs clear beautiful light, the primal sounds of trickling water, dampness on your cheeks, the negative ozone of running water. Gober has recreated an actual working ecosystem with pumped water running over handmade rocks, stones, moss, eddying around dead leaves, twigs, and sticks. I thought of the artificial waterfall in DuchampÔÇÖs ├ëtant donn├®s. ┬áI fell into a standing trance. I stopped looking for meanings and surrendered to this island beyond reason. I was freed, however temporarily, from everything. Instead of looking through DuchampÔÇÖs peephole in a door into the body of a splayed-legged woman, GoberÔÇÖs waterfall lets us look into ourselves.

For me, Waterfall transformed into a kind of confessional. I left the larger political world and inverted my gaze. First, I remembered that none of us can ever really know whatÔÇÖs inside anyone else, what theyÔÇÖve gone and are going through. That much of what all of us think is true comes from errors about our suppositions. That is when I gleaned that the siegelike mindset, the unspeakably isolated, sleepwalking, wounded, monomaniacally self-enclosed spirit I saw in these windows was neither frenzied America nor other people. It was me ÔÇö a person with half-drawn curtains, whoÔÇÖd grown too sure about what was happening around me. In what Amanda Gorman called the ÔÇ£overcrowded solitudeÔÇØ of our pandemic isolation, and without quite knowing it, I had become so happy in working and keeping my own company I lost the ties that bind me to other people and strangers. I became convinced that my thinking about the world around me was right, and in some sick way I wished never to return to social life.

Since March 2020, the pathologically skittish self I have cloaked in extroverted gregariousness my whole life has become ascendent. My curtains drew. Inside this self-made world, I didnÔÇÖt know it, but some of my oldest demons spoke to me. The last couple of years have taught me that there is a dark side to my solitude ÔÇö one I thought IÔÇÖd banished. The part of me that withdrew from people in my 20s and in my 30s filled me with envy, rancor, self-pity, contempt, imperiousness, striking out at others first in fear that IÔÇÖd be rejected as an imposter. Waterfall made me know that I was becoming that self again. I was scared.

I had internalized the last five years of political upheaval, two years of pandemic semi-isolation, witnessing in rapid succession the murder of George Floyd and one of AmericaÔÇÖs political parties turning authoritarian. All this is a form of personal social death and collective trauma. I feel a disconnected sense of loss, melancholia, and homesickness. I find myself pining for things that never happened, wishing for what others might have, and am disappointed in opportunities that disappeared once the pandemic began. I had a book published the day America went into national lockdown and had to cancel a 45-day book tour. Such self-pity in the face of nearly a million dead Americans is off, disturbing. Yet I think we all have similar feelings. There is a free-floating low-level anxiety and deprivation. All of us have ceased to exist in relation to one another. This isnÔÇÖt fully human. I think I, we, are in a simultaneous state of shock and mourning.

I see it when I go out now to openings, small dinners, and gatherings. I am ecstatic, thrilled. I bounce from person to person, giving and getting feedback. But instead of acting right, I am being dickish, barking at people, being snappy, gabby, tone-deaf, missing social cues, acting gruff. I have made good people feel bad while telling myself this is okay because I knew the score. I hear myself give orders to acquaintances, telling others how to do this or that. I have been looking down on other peopleÔÇÖs goals, on the one hand, and judging others for not reaching those goals, on the other. I have become this bossy political-guru, cable-news-panelist, Twitter-speaking narrator in DostoyevskyÔÇÖs Notes From Underground. My social reflexes are shot. I am the self I thought IÔÇÖd imprisoned all those years ago. I tell myself that no one notices. But I notice: I have transformed my beautiful art world aviary into a private nest. I am an ostrich thinking I am invisible when everyone has a clear view of me.

IÔÇÖve lost so much by being too happy in my solitude. Pattern and habit set into my life. My empathy, accountability, and flexibility have eroded. My imagination became a monologue rather than the cultivated coral reef of my interactions with others, strangers, friends, artists, gallerists, other critics, anyone. I stopped. I shied away from experiencing the fullness of running into someone, exchanging confidences, trading trivialities and gossip, trying out new ideas, learning things I didnÔÇÖt already know, seeing where IÔÇÖm wrong or only listening to my demons, or just having to deal with pangs of jealousy and fits of social-professional indignation. I do not know if the past few years have done this to others, and, if so, to what extent might many of us have become some of the worst versions of ourselves in our extended isolations. For me, I know that beyond this, lies nothing.

Sartre was wrong: Hell is not ÔÇ£other people.ÔÇØ Hell is being around only people exactly like yourself, or perhaps only yourself. In his tender mercies, Gober opens the sluices of this mystery that let us feel part of something bigger and to glimpse a promise of new beauty.