When contract disputes and creative differences sent veteran Marvel comics artist Jack Kirby — the man who co-created Captain America, the Avengers, and the X-Men, among others — into the arms of DC Comics in 1970, New Gods was born. It constituted a thematic continuation of the stories he’d been crafting for the Asgardians in Thor, featuring an original pantheon of characters powerful to the point of godhood. The New Gods were divided into two planets: Genesis, a world of peace led by the Highfather, and Apokolips, a planet of cruelty ruled by the despot Darkseid. The two opposed civilizations had struck a deal: The sons of Highfather and Darkseid would be traded, so Apokolips-born Orion would grow up on Genesis and Genesis-born Scott Free (better known as Mister Miracle) would be raised on Apokolips. The arrangement was part treaty and part experiment; neither world would wage war on the other with a prince in the way, and it could settle the question of the nature versus nurture debate, too.

But the series didn’t perform well at the time and was canceled in 1972, leaving a climactic battle between Orion and his father Darkseid unresolved. There are no New Gods movies currently streaming on HBO Max, although Ava Duvernay nearly adapted it and several of Apokolips’s villains feature in Wonder Woman and Justice League. Still, the story proved to be an influential property in DC’s superheroic canon, with Darkseid going on to fight Superman numerous times and become the central antagonist of the Great Darkness Saga over in Legion of Super Heroes and the Final Crisis miniseries decades later.

More than that, New Gods proved influential across the comics aisle. The story of the Eternals, who feature in the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s 2021 entry named after them (which is currently streaming on Disney+), owes a lot to the demise of New Gods. After its end, Kirby bounced around various DC projects before once again growing creatively dissatisfied and jumping ship. By 1975, he was back at Marvel, and one of the first things to spring from his pen was 1976’s The Eternals. Having previously drawn on Norse mythology to build his deities, Kirby drew from Incan history this time around; the gods once worshipped by Incans, he suggested, were in fact a divergent evolution of the “Dawn Ape” — mankind’s progenitor. The Celestials, gigantic and inscrutable ur-gods, created both the Eternals and their nemeses, the Deviants, alongside humanity but distinct from it, from a prehistoric ape. The Eternals were “few in number” and “immune to time and death,” and each of them possessed unique powers, while the Deviants were “ever-changing and destructive,” an unstable species that mutated in new and monstrous ways with each new generation, prone to constant warfare. The Deviants sought out the depths of the Earth to hide, and the Eternals took to mountaintops, forming vast cities like Olympia in Greece and Polaria in Siberia. Eventually even these peaks would prove lacking, and the Eternals took to space, only visiting Earth occasionally to check in on humanity’s progress.

Kirby’s original Eternals story isn’t set in the time of the Inca, but centers around the Eternals’ return to Earth in modern times. His lead is the golden-haired and golden-eyed Ikaris, who, under the alias Ike Harris, leads a father-daughter pair of explorers into an ancient underwater Incan ruin and reignites a beacon that leads the Eternals back to Earth — and right behind them, their creators. The impossibly old Celestials stand in judgment of all intelligent life; if the Eternals (and New Gods and Asgardians) reflect the enormity of polytheistic pantheons, the Celestials rise above even that, with the power to end entire planets. Moviegoers have seen at least a few Celestials on the MCU screen — the colony of Knowhere, featured in Guardians of the Galaxy, exists in the skull of a dead Celestial. Later in the same film, the Collector (Benecio Del Toro) views footage of the Celestial Eson the Searcher. And while he is definitively not a Celestial in the comics, the cinematic version of Ego the Living Planet (Kurt Russel) claims to be a Celestial in Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2.

The Celestial Arishem the Judge is the first to appear in the comics. Massive and encased in red armor, he does nothing when he arrives but stand atop a rock and judge Earth’s progress (according to metrics known only to the Celestials themselves). The set-up: If he judges in Earth’s favor, the planet lives, and if not, Earth is to be destroyed. More directly interested in the Earth’s destruction are the Deviants, who are eager to expand an empire, as they once did in the days of pre-history. To this end, they’re ruled by a squat, green Deviant named Tode, who commands an underling named Kro. Kro, a largely human-shaped creature with reddish skin and the ability to manipulate his own atomic structure, would go on to become a central antagonist in the Eternals’ saga. Within the first few issues, he uses his powers to grow a pair of horns, so that he might resemble the Devil and play on humanity’s fears.

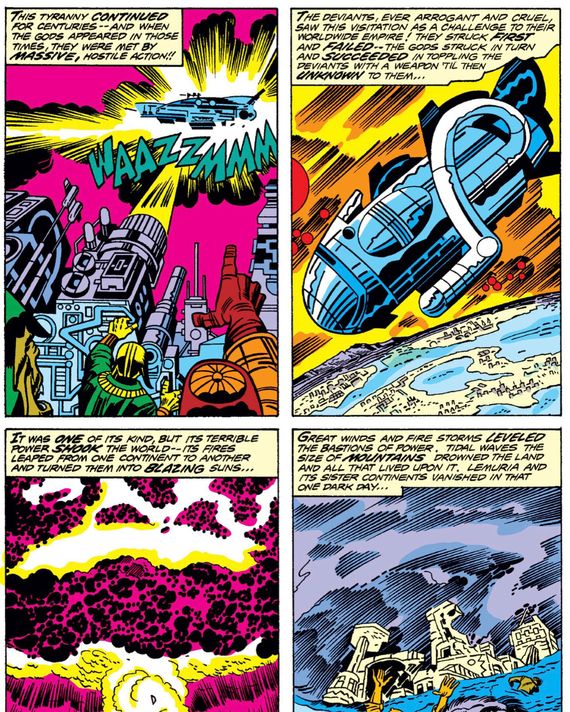

After Ikaris, Kirby introduces Ajak (named after the Greek hero Ajax), Sersi (after the Greek figure Circe), Makkari (after the Roman god, Mercury), Zuras and Thena (after Zeus and Athena), and more. While each Eternal’s powers vary — for instance, Ikaris can levitate and shoot energy beams from his eyes, while Makkari has super-speed, and Thena is a masterful hand-to-hand combatant and scholar — all Eternals generally have the same abilities. They include invulnerability, longevity, and immunity to disease, as well as teleportation, some low-level telepathic ability, the ability to project illusions, and complete molecular control over their entire bodies. In crafting their individual and collective storylines, Kirby wove in not just fantastic fiction, but his own ideas about religion and humanity, his feelings about global politics, and even elements of his time serving in World War II. For example, in recounting the ancient history of the Eternals and Deviants, he describes a pre-emptive strike akin to Pearl Harbor followed by a mushroom cloud retaliation that is roughly analogous to his perception of U.S. involvement in World War II. Here, Kirby not so subtly equates his gods with American forces, and the monstrous deviants with the Japanese.

But the lines between the Eternals and Deviants did get blurry; within a few issues, two Deviants are shown living under the protection of the Eternals, away from their own kind. Kirby leaned on the idea of “good” people and “evil” people, but he also repeated the same trick he pulled with New Gods, placing paramount importance on a given character’s moral choice in a moment. A character could be born a Deviant, but choose the path of good, and vice versa. Take Druig’s betrayal of his fellow Eternals, culminating in his attempt to destroy one of the Celestials in the book’s final issue.

Unfortunately, like New Gods before them, The Eternals was canceled after 19 issues due to low sales, leaving plotlines unresolved once more. Marvel revived the series a few times throughout the years, and each revival was shorter than the last; as of this writing, there are a grand total of 56 issues starring the group. The second volume of The Eternals was a 12-issue series started by Peter Gillis, finished by Walt Simonson, and released in 1985. It continued the group’s story, with Thena leading the Eternals following the demise of Zuras. The Deviants’ loyalties are split between Kro and a new character, the leader of a religious sect by the name of Priestlord Ghaur. But Ghuar’s ambitions, like Druig’s in the original series, result in his own annihilation. By the end of the series, Ikaris, arguably the main character all along, assumes leadership (after Thena began a love affair with Kro). There wouldn’t be another Eternals series for 20 years, though some of the characters kept busy in the meantime. Several joined the Avengers in various capacities, and a story arc from Avengers #246-248, by Roger Stern and Al Milgrom, established that there were Eternals offshoots known by different names. The most notable of these is familiar to moviegoing audiences: His name is Thanos.

So the story goes, Thanos is one of two sons of the Eternal known as A’lars, or Mentor. A’lars was a brother to Zuras, who left Earth to form a civilization on Titan, the moon of Saturn. There, with another Eternal named Sui-san, he fathered both Thanos and his brother, Eros. Thanos and Eros were originally created by Jim Starlin in 1972 for the pages of Iron Man, and were not originally intended to be Eternals, though they were based on Greek myth. It was not until the pages of Avengers nearly a decade later that the link between the Titanians and Eternals was established. By then, Thanos’ brother Eros was known more widely as Starfox, and was a card-carrying member of the Avengers right alongside Sersi.

Marvel finally began publishing a third volume of the Eternals in 2006, penned by Neil Gaiman with art by John Romita Jr. Internecine squabbles were common, resulting in multiple betrayals. For example, Sprite, an Eternal who lives forever in the body of a child, hatches a scheme to kill his fellow Eternals and to render himself mortal so that he might finally age. His plan fails, but not before another Celestial known as the Dreaming Celestial nearly ends the world. In one of the third volume’s final and most disturbing scenes, Zuras catches up with the pint-size trickster turned murderer and quietly snaps his neck aboard a train.

Death, of course, is rarely the end — for Sprite or any of the other Eternals. If Kirby presented the characters as a kind of space-faring, exploratory people, deity impersonators who shaped the course of human history, Gaiman codified the idea even more clearly. He ritualized the idea of Eternals not as simply immortal, but as extremely long-lived super beings who are resurrected by ancient Celestial-designed machinery to continue their work of standing in preservation of Earth. He built on the initial cyclical ideas presented by Kirby’s original work; the Eternals live to defend, maintain, and preserve Earth, then eventually die, only to rise again and repeat the process.

A new Eternals, penned by Charles Knauf with art by Daniel Acuna, began in 2008 focused on continuing Gaiman’s modernization of the franchise. Though it was canceled early, it prompted the Celestials move toward the forefront of Marvel lore. After the Dreaming Celestial of the 2008 volume awoke and stood above San Francisco, he was often seen in the background of X-Men comics set in the Bay Area. Celestials featured prominently in Uncanny Avengers, a mixed team of Avengers and X-Men designed to heal tensions between mutants and superheroes in the aftermath of a large-scale conflict that pitted the two groups against each other. (X-Men-Celestial history goes back further; it was the Celestials who created the Life and Death Seeds, artifacts with the power to jumpstart creation and extinction, and a common tool of the villain Apocalypse.) Most notably, an entire army of Celestials appeared as the antagonists of Jason Aaron’s 2018 run of Avengers, a conflict that once again resulted in the Eternals dying, this time without even the benefit of a book of their own.

But last January they returned with a fifth volume, written by Kieron Gillen and Esad Ribic, the story’s rise and fall forever reflecting the cyclical nature of its narrative conflict. If the post-credits scene of the new Eternals movie is any indication, the Marvel world and the Marvel Cinematic Universe are hardly done with Kirby’s invention.