When Angelique Kidjo accepted her 2016 Grammy for Best Global Music Album, she forecasted a future well beyond her own accomplishments. “I want to dedicate this Grammy to all the traditional musicians in Africa in my country, to all the younger generations that knew our music,” the Beninese artist said. “Africa is on the rise.” It was a bold premonition, and one without much precedent in the United States. For a long time, the Grammys and American music industry at large relegated artists like Kidjo to the nebulous genre of “world music,” which, alongside Latin pop and reggae, remained one of several niches that were stratified not by any technical criteria, but by a vaguely colonial pan-ethnic taxonomy. It’s why salsero Marc Anthony, rocker Juanes, and música urbana artist Bad Bunny could receive the same award, despite having disparate musical skill sets, or why Best Reggae Album frequently featured dancehall artists; adherence to indigeneity is not the standard.

Given such context, the announcement that Billboard has launched a U.S. Afrobeats Chart merits further interrogation. While ostensibly a monumental stride in acknowledging music within the Black diaspora, shifts as significant as these are almost always a belated reaction to ongoing evolutions, as opposed to an organic development established in collaboration with the autonomy of the artists in mind. When the threshold into Western ubiquity is crossed, reassessments are made and hierarchies are restructured to adjust to the market needs of the American consumer. That held true for Ricky Martin; his fourth studio album, Vuelve, garnered a Grammy win for Best Latin Pop performance. But it would be his self-titled fifth studio album, in 1999, and the tour de force “Livin’ La Vida Loca” that would catapult him into the hallowed status of mainstream pop, with an appearance on the Pop Airplay chart and Grammy nominations for Song of the Year, Best Male Pop Vocal Performance, and Best Pop Vocal Album. Despite already being an American citizen as a Puerto Rican, Martin needed to capture the interest of Caucasian audiences before cementing the kind of cultural relevance the Recording Academy rewards. Billboard followed a similar path, when it created its first Latin chart, Hot Latin Songs, in 1986, before launching the Latin Billboard Music Awards in 1994 (it would also add Tropical Airplay for the Caribbean, Regional Mexican Airplay, and Latin Pop Charts that same year). But those moments fell far short of building a solid framework for the immense Latin music market in America, relegating the eventual rise of supernovas such as Bad Bunny or hits like “Despacito” as inexplicable phenomenons. Whether Afrobeats avoids that same convoluted path is an open question.

The African diaspora has long had an interplay with American pop culture, but mostly by way of sanctifying breakout stars into a prestigious class of gifted musicians. There was Miriam Makeba’s breakthrough as “Mama Africa” in the 1960s, Fela Kuti and Ali Farka Touré’s jazz-influenced works in the ‘70s and ‘80s, Koffi Olomide’s Quartier Latin and the soukous wave of the ‘80s and ‘90s, and Kidjo’s popularity in the ‘90s and beyond. Despite their critical reverence, these artists were still largely grouped as “international,” competing alongside the likes of Ravi Shankar’s sitar and Sergio Mendes’ bossa nova. As David Byrne wrote in a 1999 essay for the New York Times, this kind of classification was “a convenient way of not seeing a band or artist as a creative individual, albeit from a culture somewhat different from that seen on American television. It’s a none too subtle way of reasserting the hegemony of Western pop culture. It ghettoizes most of the world’s music.”

While artists of the Black diaspora have interacted and influenced each other for decades, dedicated infrastructure to the discovery and development of African musicians within America has only recently emerged. The mid-aughts were dominated by communities of first-generation West African immigrants and their children in enclaves such as New York; the greater Washington, D.C., area; and Houston, where both popular and classic songs from the continent were played at parties and events. As Nigerian DJ Neptune told Rolling Stone in January, “It was obvious that [Africans living abroad] were craving their own [music], because that’s one of the ways they could connect back home.” The rise of the blog era and social media facilitated ease of access as the increased wave of styles being consumed from West Africa — from highlife to azonto, fuji, Afro-pop and Afro-fusion — began to coalesce under the label of Afrobeats, with the plural “s” denoting the distinction between the contemporary potpourri and Fela’s signature long-form Afrobeat. But the new name has led to growing pains. “In the rat race for crossover success, Africa’s biggest pop stars and their backers have been preoccupied with creating a palatable brand for U.S. and U.K. consumers while losing sight of the long game — retaining ownership of culture,” wrote Korede Akinsete for OkayAfrica in her essay “Call Us by Our Name: Stop Using ‘Afrobeats.’” “For African pop music to command the level of respect that is reflective of its influence, artists must divorce themselves from the idea that crossing over to Western markets is the highest privilege.”

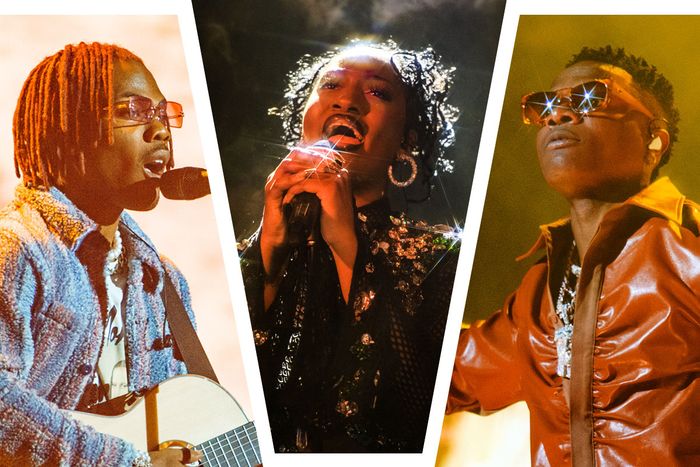

The 2010s came with notable evolutions. Chris Brown and Meek Mill were two of the first American artists to jump on international collaborations with African artists. DJs in the United States, noticing the momentum, started spinning Afrobeats sets on radio shows and during club nights. Spotify would later launch a Global Cultures Initiative with an Afro Hub. Drake dropped “One Dance” with Lagosian superstar Wizkid — netting the rapper his first Hot 100 No. 1 — and recruited alté R&B singer Tems for a feature on Certified Lover Boy. Beyoncé released an album-cum-short film, Lion King: The Gift/Black Is King, a stunning visual undertaking featuring some of West Africa’s preeminent contemporary talents, including a solo track from the African Giant himself, Afro-fusion star Burna Boy. The digital scramble for Africa was in full thrust.

The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic would send the continent’s cultural reach into a new stratosphere. It’s hard to imagine the first few months of lockdown without hearing the thumping bass of Afroswing anthem Young T & Bugsey’s “Don’t Rush,” which quickly served as the instrumental backdrop for endless before-and-after videos in the #DontRushChallenge on TikTok, helping land the artists remixes by American hip-hop acts DaBaby and Busta Rhymes. By the end of 2021, it was rare to visit Tokboard — a site that aggregates usage trends on TikTok’s top sounds — and not find CKay’s “love nwantiti” on its leaderboard. The tender Afrobeats song originally debuted in Nigeria in 2019, but found a second life during the pandemic once Winnie Harlow played it in a Diddy livestream; by the end of December it was the most Shazamed song of year. Similarly, Wizkid’s Made in Lagos dropped in October 2020, but its breakout single, “Essence” — a downtempo melody with heavy R&B influences courtesy of fellow Nigerian Tems’s contributions — was re-released in April 2021, and immediately gained momentum. Justin Bieber ended up on the remix, helping it sneak into the Hot 100 top 10; Fireboy DML made the same move with Ed Sheeran on his hit “Peru,” which hit No. 6 on the Rhythmic Airplay charts.

This progress has been significant. Still, impact notwithstanding, news of the Afrobeats chart fails to provide new insight or clarity into still-nagging questions. Mainly, what is the rubric to apply for a genre? Does it need to have an artist of African descent? Is a pidgin or West African language required? Are specific instruments or musical stylings necessary? More broadly, will this chart be in service of the artists currently relegated to the miscellaneous margins of commercial breaks and ambiguous categories or is it little more than a marketing gimmick? The first chart predictably has CKay leading the pack, but three of the remaining top five are songs with features from either Bieber or Ed Sheeran — a development that seems to augment even more fractures in the current system rather than expose the world to new artists. Inquiries around the ontologies of these musical works and the parameters that offer it authenticity are not novel — in 2020, Burna Boy was up for Best World Album for African Giant, while Bey’s Lion King: The Gift Album was slotted in Best Pop Album. This arose when Drake jaunted into more international sounds as well; even domestically, there have been conflicts, with Billboard struggling to categorize Lil Nas X’s Old Town Road.

As it currently stands, the Afrobeats chart piques interest, but the rising crop of artists deserve more than a marketing cash grab or optics without a meaningful methodology behind the approach; with continued creative investments such as the upcoming Netflix documentary on the history of Afrobeats, the cultural workers who were responsible for bringing this phenomenon stateside will continue to be able to set the record straight about the origin and growth of this amorphous genre. Hopefully, the new Billboard chart is the beginning of an invitation to collectively determine these parameters together, and not defer to what is most convenient, palatable, or marketable to record label executives.