$550 million.

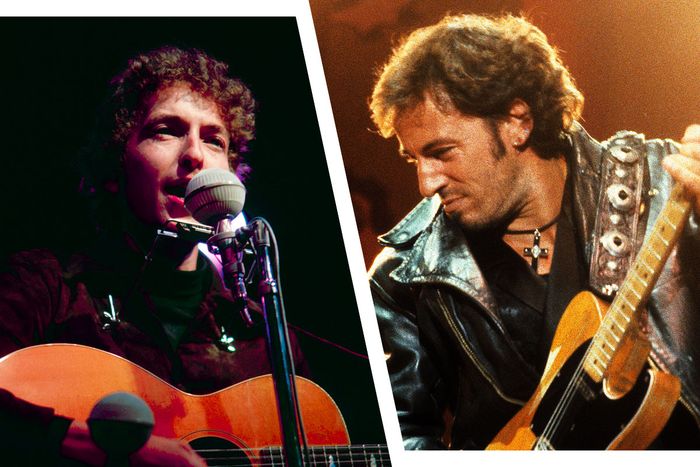

That’s the reported amount of money the Boss himself, Bruce Springsteen, commanded when he sold his recorded work and songwriting rights — or, to put it simply, the rights to his entire body of music — in a blockbuster deal last year. The sale was the largest ever for a musician’s catalogue, and many legacy artists have since followed suit: Nice fellas Bob Dylan, Sting, Neil Young, and Paul Simon have raked in hundreds of millions of dollars for their life’s work, as have tenured acts including Stevie Nicks and Red Hot Chili Peppers. It seems rarely a week goes by without a “Sells Catalogue” headline making the rounds, and with some deals going for undisclosed amounts, this doubles as a fun guessing game, too.

Yet somewhere between Tina Turner and Neil Diamond walking away victorious from the negotiating tables, Vulture had a bit of an existential crisis about what it means for musicians to sell their catalogues today. Are the prices overvalued? Undervalued? And what exactly is being bought by these corporations and record labels, anyway? George Howard, a strategic consultant and distinguished professor of music business and management at Berklee College of Music, was nice enough to explain how this trend speaks to larger issues in the industry, how Dylan’s sale may be the biggest anomaly of them all, and the longterm effects these deals have on music. “Commoditizing art,” he puts it, “never works out that well over time.”

With these catalogue announcements, I’m seeing two terms that represent different things: songwriting rights and music rights. What’s the fundamental difference between them? Or rather, what exactly is being purchased with each?

In any song, there are two copyrights. One copyright attaches to the melody and the lyrics. If you don’t have a publisher as a songwriter and you are your own publisher, you exclusively control the melody and lyrics. So, for example, Dolly Parton wrote “I Will Always Love You”; a number of years later, Whitney Houston does a cover version of the song and releases it with the record company that represents her. The record company holds the copyright to what’s known as the “sound recording,” or the “master recording,” but Dolly Parton continues to get royalties when Whitney Houston covers that song, when it’s sold, or when it’s performed on the radio. Then there’s a copyright for the rendition of the recording, which is held by the label or the performer. With a lot of these deals that have been sold, it’s typically around the publishing side. So if you’re Bob Dylan or Neil Young or you’re selling your underlying rights to the melody and the lyrics, you often don’t have the right to sell that master recording because it’s owned by the label.

Which of these copyrights is considered most valuable?

Historically, publishing has always been more valuable. To use Dolly Parton as an example again, you can and will make money by singing your own rendition of “I Will Always Love You.” If somebody else sings a rendition of the song, they will get a percentage of the sale from the recording but not from the public performance. In other words, when the song is played on the radio, it’s known as the “mechanical royalty,” which is when the song is reproduced and distributed. If you’re Bob Dylan and you write “Make You Feel My Love” and Adele covers it and 100 other people cover it, he and his publisher generate royalties through mechanical public-performance synchronization whenever that happens, whether he performs the song or not. The money has the most value over time on the publishing side because it’s like a monopoly or patent — if anybody wants to use that song, by law, the person who wrote it can’t stop them. So if I want to do a cover of “Masters of War,” he can’t stop me, but I have to pay him.

That’s interesting. You would think there would be veto power there.

Yeah, it’s all about that compulsory mechanical license. I have to pay him a royalty that’s set by the government, and don’t get me started on that. Why does the government get to set the cap? Then anytime that song is performed, by the person who wrote it or not, anytime it’s played on the radio or shown on TV or used in a movie, the royalties come back to the writer. If you think about a movie like I Am Sam, it’s full of Beatles covers; the Beatles didn’t perform any of those songs, but they wrote them. So they got the money. That’s why, if you’ve written the song, it’s the gift that keeps on giving if people are actually covering it. But to confuse matters, Spotify and the other streaming services pay out about four times as much to the sound-recording holder than to the songwriter. It has created a little bit of equilibrium. This is why the labels have become so enriched.

What about on the publishing side for streaming?

There’s a very heavily regulated license that goes to the songwriters, whereas the amount that’s paid to the record labels is negotiated, and the labels have Spotify over a barrel. That’s why these labels have all this money. You’re seeing a lot of these deals where, for example, Neil Diamond sold his publishing back to Universal Music Group. There have been a number of those deals where Hipgnosis and other song-management companies are buying copyrights, but then increasingly you’ve got the incumbent record companies buying them as well because now they’ve got both sides forever. It’s good business, I suppose. I happen to think these catalogues are getting incredibly overvalued, which is why they’re not disclosing the amounts. That’s my experience. I’m not the only one who thinks this, but if you’re getting paid some massive check, you kind of want to brag about it.

On the other hand, what’s happening is that these song royalties have been normalized because of Spotify. It’s now very predictable in terms of revenue. You can look and go, Okay, we’re pretty confident that over X number of years, just based on streaming, we will generate Y number of dollars. Any time you’ve got predictable revenue for anything, you can securitize it. Think of it as a bond. This isn’t new, by the way. David Bowie did this in the ’80s with what was known as “Bowie bonds.” So investors are looking for predictable returns that are a little bit above normal rates of interest and want some bragging rights. They’re starting to be bought by big institutions because it’s just predictable money. I have a feeling that’s why some of these sums aren’t being disclosed, because they’re going down. If I’m an investor, I’m thinking, What am I getting for my money? There was just froth at the beginning, and I think it started to normalize a little bit.

Your comments about overvaluing catalogues piqued my interest. There are lots of musicians who sold for an “undisclosed amount.”

They’re overvalued, but you still want to sell them. If you’re 75 or 80 years old, and these are your assets that you’ve worked your life on, this is your moment to cash out and set your family up for generations. It’s a little heartbreaking, but I get it. It’s the same as somebody who has a company to sell. The difference is that you can’t just pass, or it’s harder to pass, down your songs. If you’re a songwriter with a big collection of work, it’s not like you get your kids to run that business. Your exit strategy is trickier, but now with this liquidity out there, you can understand it. If you don’t have that many more years left or you’re unable to perform — which is where the real money for many of these artists has been — their ability to earn it is not that great. There’s no other way to have that legacy. So they’re taking a premium, or they’re taking a discount. I don’t know what that says about the culture.

What else strikes you now about the seller’s market for these catalogues?

I think generally the prices are inflated because it’s very much a seller’s market, where everybody thinks these catalogues are both sort of sexy and can be securitized and de-risked. Unless they find new ways to exploit them, that’s what they’re betting on.

Does any musician come to mind who you think was either hugely under- or overvalued?

I felt Bob Dylan was undervalued.

Why is that?

I think the disclosed amount was $300 million, and that was for both the writer’s share and the publisher’s share. He said to whoever bought it, Here are the rights, full stop, to my copyrights. Do with them what you will. I, Bob Dylan, now will never receive any royalties when they’re performed. Knowing Bob’s manager as I do, he doesn’t make bad deals. I’m not sure if what was disclosed is accurate, but that amount of money didn’t sound right to me in terms of the sheer vastness of his catalogue and the number of covers. Bob has a 60-year career of writing timeless and enduring classics, generation after generation, which have been covered by thousands of people and will always be played. The amount he received seemed low to me just based on his number of copyrights, his impact, and the number of his songs that get covered. But again, these are valued at what someone’s willing to pay. But I’m sure it was the right deal for Bob.

As is so often the case with Bob — and his was one of the first high-profile deals — he manages to look around the corner, then other people catch up. But nobody does it quite like him. These are works by an artist that mean so much to people on a very emotional level. It’s a general feeling of sadness for me that it has just become commoditized to this degree. You can look at it as, hooray, these people are getting more or as much as they deserve for this great art. But as another way, you can look at as they’ve just kind of given up: Yeah, screw it. This song is no different than some patent on something. Have at it. But I’m undeterred. If this provides more interest and opportunities, that’s great. But we have to remember that art and music are not the same as a stock certificate.

What do you think about younger musicians selling their catalogues? John Legend and Jack Antonoff both sold for undisclosed amounts.

We’re in a hype cycle. Assets are getting overinflated. But if you’re on the sales side of that moment, you have a decision to make. You have to think, Maybe this continues to go on, and the hype cycle goes on forever, or I’m selling too early, or Maybe prices normalize, and I better get this catalogue while the getting is good. You’ve also got to understand that it’s not just an artist or songwriter looking around for deals. There are so many people involved in these types of transactions, all of whom have a vested interest. If you’re some banker or broker, you are literally scrounging through every Rolodex you have, going, Who has copyrights? Because there are buyers out there. So you’re sitting there, let’s say Jack Antonoff, and someone calls you up and says, “Hey, they’re willing to give you millions of dollars.” It’s hard to turn that down, particularly if you’re younger in your career. I’ve seen this for 30 years. There’s bad Dunning-Kruger in the music industry. You have bankers and others who are very sophisticated in financial transactions and who assume not only that they understand how the music industry works but that they can make it work better than those who have been doing it for decades. That tends to end in tears.

There’s been a lot of times when the music industry has fallen ass-backwards into profitability, going back from piano rolls to cassettes to CDs to streaming. There were a lot of people thinking, Yeah, this will kill us. Streaming is the most recent one that actually saved the industry. If you look at the music business circa 2005 — post-Napster but pre-Spotify — it was horrible. It was really hard for labels and artists, then Spotify came along and said, Oh, here’s a fire hose of money. But will that fire hose continue? Will other forces change? It remains to be seen.

More From The Ask an Expert Series

- A Real Manager Gives Lumon a Performance Review

- Don’t Expect a Drake Trial

- Making Sense of the YSL Trial’s Wild Ending