Most people would call the cops after finding out that their landlord is illegally spying on his residents’ every move, but not Sharon Stone in Sliver. Stone’s character, Carly Norris, is a buttoned-down book editor who specializes in tell-alls and unabashedly elbows someone aside at a cocktail party to get a better look at a couple having sex without the curtains drawn in a nearby building. A wolfish grin stretches across her face as one of the guests yelps, “She’s a voyeur! She can’t get enough!” No one would ever accuse the erotic thriller of being too subtle. Carly likes to watch, and so does her eventual lover, Zeke Hawkins (William Baldwin), who lives a few floors down in the Manhattan high-rise she just moved into and who, it turns out, also owns the building. Zeke, in fact, likes to watch so much that he has had all the apartments rigged with hidden cameras, the live feeds transmitting to a state-of-the-art room in the back of his bachelor pad.

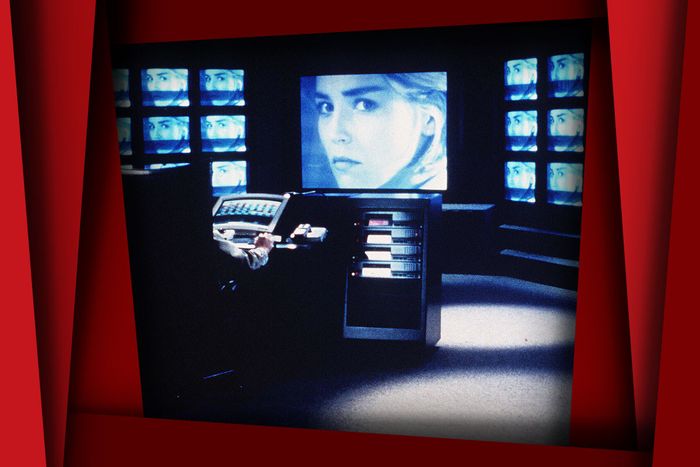

The first time Zeke shows Carly his surveillance chamber, she storms out in disgust. Then, unable to help herself, she comes back, settling in for a long session of spying on her oblivious neighbors, so enrapt that she forgets to eat. The ability to commune with the illicit footage in an intimate setting, flipping between channels, almost matters more than what she’s seeing. It takes hours before she figures out that Zeke has a tape of the two of them fucking, and that they can watch themselves while fooling around. Basic Instinct may have secured Stone’s place as the icy blonde queen of the erotic thriller in 1992, but it was Sliver, made a year after, that highlighted a fundamental truth about the genre — that it was as obsessed with home video as the customers who enabled it to become such a phenomenon in the 1980s and ’90s.

The erotic thriller famously brought a flurry of sex and death to the multiplex, but its existence really owes everything to home viewing — to late-night cable, down-market sequels, and direct-to-video offerings. While Blockbuster refused to carry porn, it would carry a copy of In the Cold of the Night, starring Jeff Lester, Shannon Tweed, and some off-label use of a container of decorative marbles. The internet had yet to really make its arrival, but the home theater had become commonplace, and the erotic thriller thrived in private, on Skinemax or via VHS clamshells squirreled home to be watched on suburban living room screens with the curtains drawn. So it’s fitting that the genre was just as in thrall with the idea of home viewing as its primary audience. Scopophilia and surveillance were two of its regular preoccupations, but so was the possibility of having illicit recordings on tape — as leverage for blackmail, as stroke material, or simply as something that can be kept and revisited whenever the urge strikes.

There was a novelty to that control, to not just be able to watch but to rewatch. The roots of the erotic thriller are in film noir and Hitchcock, with all the subtext said out loud. Brian De Palma’s proto-classic of the genre, Body Double, is a jubilantly debased remix of Rear Window and Vertigo with added tits, with an invertebrate Craig Wasson as struggling actor Jake Scully, who obsesses over a woman he believes may be in danger without ever being able to spring into action to save her. But Michael Powell’s 1960 shocker, Peeping Tom, about a man who films the murders he commits, feels just as essential as a forerunner. To Mark (Carl Boehm), the wretched loner of a main character, the violence itself is less significant than the celluloid record he creates, and he carries a camera with him everywhere, often surreptitiously filming. He may not have the benefit of ’90s-era technology, but like Zeke in Sliver, he secretly owns the building he lives in and gets romantically involved with one of his tenants. And like Zeke, Mark has a back room where, using a projector rather than a close-circuit television, he obsessively reviews the surreptitious footage he has shot, as though the ability to watch in private gives him more control over the world outside.

Peeping Tom may be about a character who gets off on the fear on his victims’ faces, but the erotic thriller usually aims for the more quotidian pleasures of voyeurism. Zeke zooms in to watch the oblivious Carly masturbate in the bath while believing herself to be alone. Will (Andrew Stevens), the meathead hero of Night Eyes, totes a VHS cassette of his unknowing client home to watch the moment when, while having sex with someone else, she locks eyes with the camera she doesn’t know is there. A direct-to-video release that spawned a whole gauze curtains–heavy franchise, Night Eyes is about a security guard hired by a rock star to install a system of hidden recording devices in his house in order to get fodder for his lawyer on his soon-to-be-ex-wife, Nikki (Tanya Roberts). Nikki knows that Will has been brought on to protect her, but not that he’s being paid to surveil and inform on her, and before long he’s falling in love with her by way of those tapes — his own DIY softcore rentals — while wallowing in guilt. Then he finds himself appearing on one of them after acceding to her request to enact a rape fantasy, and understands that the unfiltered truth they seemed to offer is just an illusion when the footage is used against him.

The unyielding truth of video, on the other hand, is key to the whole premise of the 1995 bomb Jade — which signaled the beginning of the end of the erotic-thriller heyday, as well as David Caruso’s movie-star dreams. A sordid, strange affair written by Joe Eszterhas, Jade is named for the alter ego of Linda Fiorentino’s character, Katrina, who is a well-known clinical psychologist married to a prominent attorney (Chazz Palminteri), but who is nevertheless able to anonymously moonlight as a high-end escort. The implausibility of being able to maintain such a neatly bifurcated double life in the relatively small world of San Francisco just adds to the surreality of the moment when Katrina’s secret is revealed. Unbeknownst to her, a hidden camera was set up to capture footage of her clients for blackmail purposes, and her face comes into view and is freeze-framed mid-act when the tape is played for her in front of an audience of cops and DAs. Her husband whisks her away, surprised and humiliated by the revelation and by having been exposed as a cuckold in front of his peers. That said, he’s also aroused, primed to follow up their fight with some sex. “Did the tape turn you on?” Katrina asks tartly afterward.

There’s something approaching dream logic to Jade, though it has nothing on In the Cold of the Night, a neon-soaked direct-to-video production that managed to look better than just about any other film in the era and meanders toward a late turn toward science fiction. Jeff Lester, playing a fashion photographer named Scott, has been having repeated nightmares in which he murders a woman (Adrianne Sachs) he doesn’t recognize. When that same beautiful stranger rolls into his studio on a motorcycle one day, what can he do but start sleeping with her? Then one afternoon he pops on a selection from her laser-disc collection and finds that it somehow contains a recording of one of the visions that has been plaguing him. It’s impossible to make sense of the explanation offered in the final act of In the Cold of the Night, except as a warped end point for the panic and fascination with home video running through the erotic-thriller genre. Rather than a tool for exposure or surveillance or a means of creating a false narrative, it’s actually a source of violence, projected into the mind of the film’s hero before he ever acts out.

Just as much as the magenta lipstick, the chokers, and the saxophone soundtracks, one of the things that grounds the erotic thriller in its particular era is how startled and titillated its characters are when confronted with the prospect of recordings of themselves, especially in vulnerable positions. Years into the smartphone era, the idea of constant documentation (or, for that matter, of racy homemade videos) is commonplace enough to make the particular shock expressed in these movies feel distant. For all that they feature their own takes on of-the-moment technology — from Zeke’s surveillance console in Sliver to the cleanup job that allows the police to get a clear shot of Katrina in Jade — they are set in a world that’s still just on the cusp of going digital, with all the changes in expectations of privacy that shift eventually brings. They’re still analog at heart, a remnant of a different time, and for all their de rigueur sex scenes and gestures toward suspense and sleaze, there’s a touch of innocence to them because of it. These people may like to watch, but they have no idea just how much will be out there competing for their eyeballs soon.

More From This Series

- 40 Erotic Thrillers You Can Stream Right Now

- The World Wasn’t Ready for Body Double

- Margaret Qualley and Christopher Abbott on Their Dominatrix Thriller