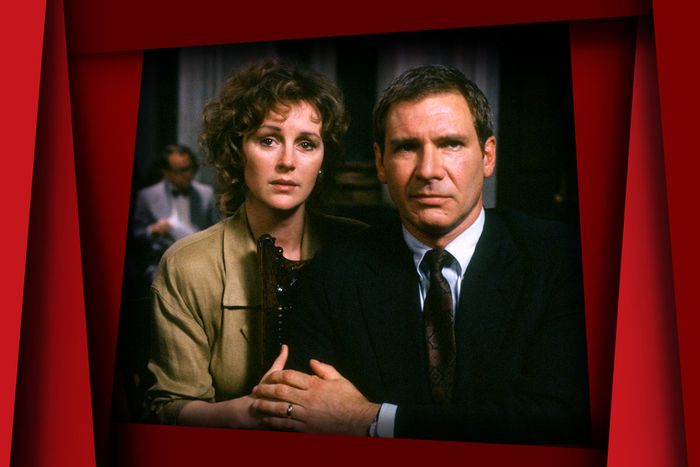

You don’t quite know what to make of Harrison Ford’s character in the 1990 legal thriller Presumed Innocent. That’s a tribute not just to Scott Turow’s gripping source novel and its skillful screen adaptation but to Ford’s performance and the ingenious idea of casting him in the first place.

Ford plays Rozat “Rusty” Sabich, a prosecutor who investigates a murder he’s eventually accused of committing. He spends much of the film trying to convince the audience and every other character that he didn’t do it. Ford’s performance draws on all the experience the actor had accumulated up to that point — from his early, menacing supporting performances in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation and Apocalypse Now to the gallery of stalwart heroes he’d built up in original Star Wars through the previous year’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade — in service of a demanding assignment: to make you care about a man who once cheated on his wife with a since-murdered woman and now cuts ethical corners to avoid being blamed for the crime. Rusty makes you believe he’s capable of shame and regret but remains just enough of an enigma that you wonder if he’s fooling you along with everyone else.

Sabich’s boss, district attorney Raymond Horgan (Brian Dennehy), is mired in a close reelection campaign. He asks Rusty, his protégé, to investigate the rape and murder of Carolyn Polhemus (Greta Scacchi), an assistant prosecutor who specialized in protecting sex-crime victims and putting their tormentors behind bars, and who also happened to have gotten around quite a bit, as they say. Carolyn’s relationships are important to the story as bread crumbs or red herrings, depending. One of Carolyn’s lovers was Rusty, and in the first of many decisions that throw our detectors out of whack, Rusty declines to tell his boss about their affair when he takes on the case. Sabich might be innocent, he might be a patsy or a pawn in a larger game, or he might be the killer. We just don’t know.

Director and co-screenwriter Alan J. Pakula reunites here with his greatest filmmaking collaborator, cinematographer Gordon Willis (The Godfather trilogy, The Conversation), who made a trio of note-perfect paranoid thrillers in the 1970s: Klute, The Parallax View, and All the President’s Men. With co-adapter Frank Pierson (Dog Day Afternoon) and composer John Williams (drawing on the musical chameleon image he built during his pre–Lucas and Spielberg days), Pakula joins Ford and a deep bench of co-stars in creating a film that’s about not merely paranoia but also acting’s role in summoning it.

As we watch the film, we become increasingly paranoid, partly because Rusty is paranoid (about getting caught, framed, or ruined) and also because, no matter how many facts and arguments Rusty and other characters provide, we still can’t answer a basic question: Does this man seem capable of murder — and if so, was it a crime of passion or cold-blooded calculation?

“It’s a difficult performance because Ford must allow the viewer to believe him both capable of murder yet wholly innocent of such barbarity,” Robert Daniels writes in “The Dark Side of Harrison Ford,” a piece about how Ford used his image as a fundamentally good-hearted action hero to confound, mislead, and disturb audiences in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, The Mosquito Coast, Frantic, and What Lies Beneath. These films require him to spend at least part of his screen time as a menace, an anti-hero, a monster, or a disappointment, setting up scenes in which his characters do things we don’t expect Harrison Ford heroes to do, such as lower his girlfriend into a pit of lava or lead his wife and kids into a jungle so he can terrorize them with messianic zeal.

Presumed Innocent has a tangled but fascinating cinema lineage, composed of strands from different variants of the thriller. Although there’s only a little bit of R-rated sex in the film, and it’s all past tense, Presumed Innocent qualifies as an erotic thriller because it’s about a romantic and sexual obsession so overwhelming that an accomplished professional man almost destroyed his life over it and is on the verge of doing so again. Presumed Innocent follows in the footsteps of classics such as The Big Clock (remade as the very good No Way Out), wherein a person who might be involved in a crime is tasked with investigating it — a position equally suited to uncovering the truth or burying it for good.

There are echoes of thrillers about men who become obsessed with a dead woman they couldn’t have and/or save (see Vertigo and Laura). Rusty was fixated on Carolyn in life, and he stays fixated after her death — a fact that Rusty’s long-suffering but loyal wife, Barbara (Bonnie Bedelia), calls out in an early scene. Carolyn and Rusty’s affair and its messy aftermath are explored in lengthy but judiciously edited flashbacks. These further confuse our ability to deduce what happened to Carolyn and whether Rusty was part of it: We’re not seeing what happened in the past but the story he’s decided to tell himself and us.

And there’s a fascinating inversion of the film-noir trope of the femme fatale. The film depicts Carolyn with more empathy than the book, which is elegantly written by Turow but told in trembling first-person by Rusty, who objectifies Carolyn and gets a bit Penthouse Forum–y in describing their sex life. Carolyn is opaque, too, but only because other people, most of them male, are telling her story or twisting it. We wonder at first if the movie is positioning Carolyn as a variant of the femme fatale, owing to her frank carnality and willingness to cut off relationships that no longer suit whatever stage her career happens to be at. But really, only somebody like Rusty would see her as a villain, and he’s a deceitful and maybe unstable man who mastered a profession that admits women reluctantly, rewards them grudgingly, and tends to slander and even destroy them when they make a man unhappy.

Rusty’s ethically compromised investigation is the engine that drives the plot, but the core of Presumed Innocent is the tragic story of Carolyn, a woman who rose quickly in a male-dominated environment, specialized in exposing and punishing predators, and conducted herself in sexual matters as certain men in that environment have traditionally done — and may have been killed for her audacity. From the start, there are lines (knowingly misogynist, as in Silence of the Lambs) and images (horrifying) that make it seem as if Carolyn was punished for something — though for what, precisely, none of the film’s incriminated men will say. She’s not a femme fatale but a maudite femme: a damned woman.

Pakula and Willis compound our difficulty with “reading” Ford by denying access to his face when we want to see it. Rusty says or does potentially meaningful things partially or fully in shadow. There are a couple of shots in which we’re looking at the back of Ford’s head while Rusty surveys a room full of people. Sometimes the camera will stay on another character while Rusty hears information we think would panic him; that the character isn’t looking at Rusty when they speak adds another layer of obfuscation: We feel like we missed something, but the other character in the scene didn’t see it, either, which means they can’t reappear later to fill in a blank.

But while Pakula and Willis make a lot of choices that help Ford create a black-box character, it’s ultimately the actor who brings him to life, unifies the movie, and undermines any verdict we might reach on Rusty — often at the moment we feel certain we’ve figured him out. The acting and filmmaking partner up especially well in scenes that are as much performance as they are a cinematic event and an idea that resonates beyond the borders of the screen. Like any did-he-or-didn’t-he thriller, this one is dependent on subtle acting and is also about acting, both as an artistic profession and as a life skill everyone must learn to some degree.

There are scenes in which Rusty “assumes” the demeanor of a guilty and very crafty murderer, talking his way through the killer’s hypothetical mind-set in the same way an actor would talk his way through a scene he’s preparing to perform. The film often cuts from a scene with Rusty in distress to one in which he’s, say, sitting quietly at a patio table talking to Barbara, looking very much like Harrison Ford relaxing in a backyard between projects, or settling into a chair opposite his defense attorney, Alejandro “Sandy” Stern (Raul Julia), his relaxed posture and crisp, unbuttoned shirt reminding us of the kinds of photo shoots stars do to promote a film. (Sandy sits across from Rusty in his own chair in a setup that variously evokes a press interview, a therapy session, and an audition.)

The overall effect is of watching an actor “turn it on” and “turn it off.” The script aids Ford by throwing in bits of Turow-derived dialogue about cheating, trustworthiness, sincerity, repression, instability, and how red herrings get tossed to juries to distract them from the truth, whatever it may be. Lawyers, defendants, plaintiffs, witnesses, and judges are performers, too. A person might be presumed innocent because they are innocent or because they gave a performance that convinced us they didn’t do it. If the acting is strong enough, we’ll never know the difference.

Presumed Innocent might be the greatest of Ford’s image-subversion experiments — right up there with the films James Stewart made for Alfred Hitchcock and Anthony Mann in which the aw-shucks, can-do, all-American superstar transformed himself into the kind of guy you wouldn’t let into your home, no matter how hard he knocked and how desperately he begged, because you knew that if you did, he might kill you.

You stare and stare at Ford, with his hangdog face and unflattering haircut, wondering if Rusty’s looks of devastation, confusion, and outrage are sincere or calculated, seeking insights sharp enough to dissect a question mark. Rusty might be innocent, he might have been framed, he might have been a pawn in a conspiracy, or he might be the perpetrator of a crime of passion, opportunity, misogynistic retaliation, ice-cold psychopathy, or some combination. Who can say? Rusty never will. Even those of us who tend to announce five minutes into a thriller that we know who did it may doubt our certitude from time to time because of how the story is told and how the hero and his character play their parts.

More From This Series

- 40 Erotic Thrillers You Can Stream Right Now

- The World Wasn’t Ready for Body Double

- Margaret Qualley and Christopher Abbott on Their Dominatrix Thriller