This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

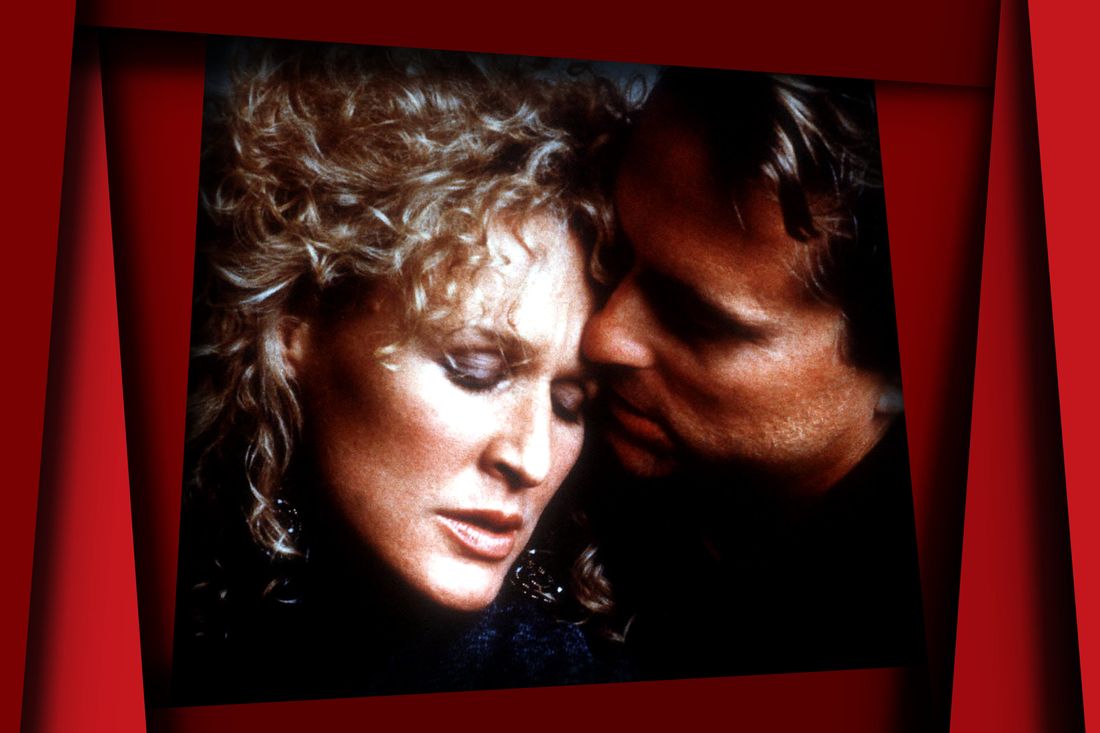

How’s this for a fantasy: It’s 1988, and you pick up a copy of Mother Jones to read about Fatal Attraction, the blockbuster everyone’s been obsessively talking about. Glenn Close stars as Alex Forrest, a hot, successful book editor who can wear a full-length leather trench coat like a dark angel. She meets Dan Gallagher (Michael Douglas), and after one weekend of hot sex, she’s smitten and he’s out the door. What happens next is probably 100 minutes of a man’s worst nightmare: the woman who will not go away. The woman who threatens his happy domestic life with his beautiful wife and child, even though he jeopardized it in the first place. The woman who will boil the fluffy bunny with the same casualness of cooking a box of Annie’s Mac & Cheese.

The article begins with a 16-year-old girl who worked at a movie theater and watched grown men react to the movie by screaming, “Beat that bitch! Kill her off now!” when Close was onscreen. A little further down, you read all about the film’s labyrinthine journey from an idea to a blockbuster. How James Dearden’s original script entered development as a sympathetic portrayal of a single woman until studio execs turned it into the story of a villainous, largely unsympathetic psycho. And then you get to this quote by the film’s director, Adrian Lyne, explaining his take on Alex and her real-life counterparts: single women in publishing who lived in studio apartments in New York (he researched them extensively):

“They are … sort of overcompensating for not being men. It’s sad, you know, because it kind of doesn’t work. You hear feminists talk, and the last 10, 20 years, you hear women talking about fucking men rather than being fucked, to be crass about it. It’s kind of unattractive, however liberated and emancipated it is. It kind of fights the whole wife role, the whole childbearing role. Sure you got your career and your success but you are not fulfilled as a woman.

My wife has never worked. She’s the least ambitious person I’ve ever met. She’s a terrific wife. She hasn’t the slightest interest in doing a career. She kind of lives with me, and it’s a terrific feeling. I come home, and she’s there.”

Well! Despite that quote (or maybe because of it), Lyne’s movies went on to become box-office hits, defining a genre, one that maintained the same casual misogyny in his interview, naturally. In the early ’90s, he cemented his reputation as the erotic thriller guy (9½ Weeks, Indecent Proposal, Unfaithful). The politics of those films never got less icky, but they remained enormously popular before flaming out entirely by the early aughts. And how could you not watch them? They were fun and thrilling and taboo and made for and about adults entangled in very adult situations that allowed them to engage with their sexual desires. Those expressions were maximalist, surprising, ridiculous, problematic, violent acts of straight-up wild fucking, like Michael Douglas and Glenn Close going at it on the edge of the kitchen counter while she splashed his nipples and hers with water from the sink. Or Demi Moore in a threesome with Woody Harrelson and piles of dollar bills (Indecent Proposal) or Linda Fiorentino riding Peter Berg, her “designated fuck,” against a chain-link fence without taking off her heels (The Last Seduction). Or Jennifer Tilly guiding Gina Gershon’s fingers across her breast tattoo just before saying, “Isn’t it obvious? I’m trying to seduce you,” and begging her to kiss her already (Bound). There were so many saxophones, so many extremely long sequences of thrusting against refrigerators or office desks or concrete walls outside buildings. Entwined bodies became wrecking balls, destroying beds and kitchens and anything — physical, emotional, philosophical — in their path.

Now it’s 2022, and Lyne and his soapy psychosexual dramas are back in the public consciousness. In March, he released his first film in 20 years, Deep Water, an adaptation of a Patricia Highsmith novel about a snail-loving husband tortured by the high-stakes sex games his wife likes to engage in; basically a perfect movie on paper. Even though there were early signs of trouble — multiple delays until eventually they bagged the theatrical release altogether — the combination of Lyne; a big budget; and two real, shiny movie stars (Ben Affleck and Ana de Armas) on the marquee seemed to signal a true rebirth of the genre. I wanted to see it, then I wanted to go to dinner and talk about it, then I wanted to go home and bone about it in a way that was maybe inspired by what I’d watched. And I wanted it to be good. Was I asking too much? Absolutely not. We deserved this. It had been so long.

But Deep Water didn’t end the dry spell. The first part of the movie establishes that Melinda (de Armas), a neo–femme fatale, loves dangling her himbo lovers in front of her quietly suffering husband, Vic (Affleck). (But why? To bait him? For the fun of it? For the kink of it?) All of Lyne’s musty moralizing is still here. Sure, it’s an open marriage that seems to prioritize Melinda’s insatiable sexual desire, but the movie’s Greek chorus of men continuously chalk it up to her hysteria. “Melinda is fucked up!” they all cry confusedly. Melinda is also completely financially dependent on her billionaire husband. The ins and outs of their (one-sided, it appears) open marriage go from intriguingly vague to murky real fast, so by the time Vic and Melinda go at it, there’s none of that long-simmering tension that makes these kinds of scenes pop.

It’s a sex scene that feels like the movie is afraid of sex. There is no foreplay, no luxuriating in the act, nothing that feels remotely kinky or surprising. (They try: Melinda asks Vic to “kiss my ass,” a weak gesture toward anilingus.) You can’t tell who is in control, who is enjoying themselves, what this sex means in the construct of their thing (is it a hate fuck? A reconciliatory fuck?). Deep Water doesn’t deliver the two elements that make the genre amazing: hot sex and high-stakes thrills that complicate how we feel about the hot sex.

It was that special blend that made an erotic thriller an erotic thriller. Even when they were regressive, even when they compelled assholes to scream sexist tirades at the screen, the genre offered a window into society’s sexual anxieties. Fatal Attraction ends when Dan’s wife, Beth (Anne Archer), kills Alex in self-defense. As the credits roll, the camera lingers on a family photo on their mantle indicating that all is right. The single woman is dead, and the family unit will survive despite her. Yet the film’s eroticism also came from the idea that the accepted power balance, and everything associated with it — marriages, livelihoods, social order, male dominance — was sitting on a precipice. Everything could go off a cliff at any moment with a flick of a red-nailed finger. So the sex had to be good — really fucking good — to justify risking all of that in the first place.

The lure of the erotic thriller isn’t just in watching something sexually taboo— if I want sex onscreen, I can find it. I can go over to HBO, where it shows 30 dicks a minute in a single episode of a series. (However, if one more person names Euphoria, the HBO show about Gen-Z high-school students as an example of sex that is sexy, I will scream. Euphoria is a show about teenagers.) What I’m missing is the feeling that the sex is not just an act but a manifestation of something we aren’t supposed to acknowledge about the ways pleasure intersects with pain and power. These films dislodged something in the cultural psyche of the ’90s, reflecting the concerns, tastes, anxieties, fears, and politics (good and bad) of the yuppies in the audience. They genuinely turned viewers on and genuinely terrified them.

You can’t just slap the ’90s on a 2020s erotic thriller and expect it to work — they have to be re-created to speak to our specific anxieties. The good thing, for erotic-thriller fans, is that many of the conversations these movies provoked are more unfinished than we like to think.

On any given Friday in 1992, you could choose from a selection of erotic thrillers that rivaled the number of options on a diner menu. You could see Basic Instinct (the Platonic ideal of erotic thrillers), Damage (Jeremy Irons as a British politician who has an illicit, tragic affair with his son’s fiancée, Juliette Binoche), The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (crazy nanny tries to kill wife, seduce husband, steal baby), Single White Female (crazy roommate tries to kill other roommate, steal her life, maybe seduce her too if the filmmakers weren’t cowards), or Poison Ivy (crazy teenage girl tries to kill best friend, seduce her father, kill her mother). Even the superhero movie of the day, Batman Returns, had an erotic thriller hidden in Selina Kelly’s plot line. (The bat and the cat … they fuck.) An embarrassment of horny and problematic content.

This was the peak of the genre. People knew exactly what to expect when they sat down in the cloth-covered movie-theater seats with their popcorn, waiting patiently through trailers: a slightly trashy (or fully trashy), cheap-to-make movie that only existed to tell a story about sex, seduction, and power. The formula is so ingrained in moviegoers’ souls we know intuitively that Black Swan is not an erotic thriller, and neither is Fifty Shades of Grey (but Fifty Shades Darker is). These movies were, as Linda Ruth Williams dubbed them, “one-handed watchers,” films that were propelled by sex, not just movies with sex in them.

The settings were lush, opulent, urban (S.F., NYC, L.A.) or a train ride away from urban (the suburbs). Steamy long shots of gloriously grimy Soho made frequent cameos. They were almost exclusively made by white men (a handful of them, specifically Lyne, Paul Verhoeven, and Joe Eszterhas) and about upper-middle-class, straight white people and their preoccupations; you could generally expect to see Michael Douglas (or a similar kind of male movie star) get led around by his dick while a fantastically dressed variation on the femme fatale had her way with/manipulated/stalked him until she got punished for it in some way (usually death). These women are what make the films memorable. I’ve always responded to their sexual liberation and determination. They said things like “Fuck me, give it to me, I want this, I want that, don’t stop”—all vocal consent and a healthy understanding of their desires. (Necessary when so much of the sex in these movies is tinged with violence.)

No matter how good the postcoital conversations about the movies were (and they were — these movies sparked excellent controversies and protests and debates), the box office reflected a waning popularity by 1995. You can blame the subsequent, long dry period that followed on one movie. “Showgirls made a real change in the culture,” explains Karina Longworth, the host of the podcast You Must Remember This, the new season of which focuses on the history of sex in Hollywood movies of the ’80s and ’90s. The movie was a team effort by two of the genre’s marquee names, Verhoeven (Basic Instinct) and Eszterhas (Basic Instinct, Jade, Sliver, Jagged Edge), and the first NC-17 movie to go mainstream. Elizabeth Berkley’s flail-acting, and the over-the-top “How did his dick not break?” sex scenes, pushed the genre into the realm of parody. Critics hated it, and it tanked at the box office. (Though the direct-to-video versions were still doing robust business, and now it is considered a cult classic simply for how audaciously bad it dared to be.)

“I don’t think we can understate how it made even the idea of going to see a movie like that so uncool. It made it difficult to take this material seriously,” Longworth says. “You didn’t want to run into your friends at the movie theater and admit you were seeing Showgirls.” The hangover lasted so long she’s not sure if a serious attempt at an erotic thriller could be received earnestly anymore. “I don’t know if people can still be as enraptured by an erotic thriller the way they demand you be. I don’t know if people can not laugh at those things now.”

Since then, the genre has gone flaccid, and like most flaccid things concerning white men, there’s been almost too much analysis of why. We ponder why the genre died every time there’s an attempt to reboot it, no matter how hollow. (In 2013, when Brian DePalma’s Passion came out; in 2015–18, when the Fifty Shades trilogy came out; in 2017, when Unforgettable came out; in 2019, when Netflix released What/If, a gender-flipped TV-series homage to Indecent Proposal. And, of course, we are analyzing it now in the wake of Deep Water.) With every piece that chronicles how they fell off, there’s a plea for them to come back. But like Alex Forrest, we just can’t accept that it’s over.

It’s possible that tastes have changed too much. I love erotic thrillers deeply, but even I can admit these movies are corny. Rewatching the classics feels out of step with our modern self-awareness; they take themselves and their seductions so seriously. Indecent Proposal’s hot-pile-of-money sex scene is hot for the first ten seconds, then the camera lingers forever as Sade’s “No Ordinary Love” swells. 9½ Weeks tried to make emptying the contents of your fridge onto your lover’s body extremely sexy, and at the time, nobody seemed to think it was a bad idea to use Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” during a seduction. Watching some of them, you get the same full-body cringe you feel when you catch yourself making a sexy serious face in the mirror and realize how you look when you’re trying to express desire. We just don’t fuck like that anymore.

The nostalgia bath of it all allows us to enjoy these movies while distancing ourselves from their obvious shortcomings. The focus on white hetero men and their hang-ups. The inability to deal with queerness (Bound is the rare exception) or race (there is no exception). Filmmakers got away with misogyny in a way that would ignite Twitter today. Enjoying Indecent Proposal meant buying into the underlying assertion: “Well, of course that rich white man is very powerful and therefore should get to have sex with Demi Moore.”

It’s easy to smugly acknowledge how out-of-date these movies are. What was considered shocking was born from the kinds of topics that dominated dinner parties in 1991. They didn’t have the same language to discuss slut shaming or the male anxiety over women’s sexual power the way we do now. What was considered taboo onscreen was way more scandalizing in a more sexually conservative climate, one where the AIDS epidemic had led to increased moralizing around sex. Because everything feels so dated, and “of another time,” it’s hard to see the organic sexiness that existed at the time. We can only analyze the power and the politics and the gender dynamics, not the primal reaction.

It also just feels easier to look backward. Because we’ve stopped being able to talk about sex — actual fleshy, part-to-part, carnal enjoyment of sex — seriously. (You could probably trace this back, in part, to the Clinton scandal, a controversy that unintentionally turned the country into prudes.) We can talk about gender politics and sexual politics, cultural criticism of sex, or the danger of sex, or why we should talk more openly about women’s desire, all with deathly seriousness. But it’s hard to have those conversations while being turned on by the act itself, which is what erotic thrillers ask us to do: to watch hot sex and have big feelings about how complicated and messy and fun it can be all at once.

To me, it’s clear we still have a use for erotic thrillers. It’s why we keep reconsidering the old ones. Nina K. Martin, erotic-thriller scholar and author of Sexy Thrills, has argued that people are nostalgic for the way sex used to be portrayed, and I agree. It’s not that we have an entirely new set of anxieties or taboos to explore (though there are certainly some new ones to add to the list). It’s that we haven’t finished the conversations we were having in 1987 and now seem harder to have in the same thorny way. There’s a reluctance in mainstream cinema to discuss the way that sex, power, danger, and pleasure are all twisted up in each other like bodies at an orgy; we’re not supposed to acknowledge the ways in which dominance, or being pursued (stalked), can be thrilling to watch and not just scary. Right now, it’s too hard to examine a feeling of “This is insane and terrifying and probably not okay, but it’s also hot!” even through the distant gaze of fictional characters. It’s hard to look at the darker parts.

At the time Fatal Attraction was written, you could see why my girl Alex was so fucking scary to men and women too. In 1987, the idea of a crazed, desperate single woman who threatened to destroy a blissful domestic sphere felt real to audiences. One of the biggest stories the year prior was a Newsweek cover story that said why a 40-year-old, single, white college-educated woman was more likely to be killed by a terrorist than to marry. With such statistics, it’s easy to create a terrifying narrative about the lengths single career women would take to get a man. (The cover story was retracted almost 20 years later, though are we still over that statistic? I don’t know.)

I recently rewatched Fatal Attraction, and instead of seeing Alex Forrest as a threat, I saw Dan Gallagher as a sinister, arrogant, entitled manbaby. Dan’s actions are easily identified as cruel and callous, and Alex’s motivations make sense from where I’m standing—a time where a West Elm Caleb can’t send dick pics to the same 15 women and get away with it. When Alex asks, “If your life’s so damn complete, what were you doing with me?” the film doesn’t answer, but we know the answer now: whatever he wants to because he can. The film’s premise that Dan is sympathetic doesn’t hold up anymore. Now, during the last shot of the movie — a slow pan over a family photo displayed on a table—you don’t feel a sense of peace because the family unit is restored. You feel a creeping sense of doom because Gallagher got away with it. He’s in black, and he’s set a little bit away from his family; his eyes are hard. The music never settles into less sinister tones. The villain still lives to fuck someone other than his wife again in six months.

So much of Fatal Attraction is outdated, but the core threat is still relevant. (Last year, Paramount+ announced it would reboot the film as a TV show, with Lizzy Caplan in Close’s role. You have to imagine it will attempt to restore the original “feminist parable.”) “There is big ‘Are men okay?’ energy in a lot of these movies,” says Longworth. “And that’s still a question on a lot of our minds.” Maybe, as Martin recommends, we need to toss out most of the playbook. She has some suggestions on how to do it: They should have glamorous set pieces and precisely five sex scenes per movie. There should be a variety of bodies, ages (no teenagers), ethnicities, partners, and intimacies. Fantasies of danger could be about engaging in new sexual practices rather than the fear of being raped or murdered. More sex, less violence.

I think she’s right, and, please, someone, get on it. Because if erotic thrillers are best viewed as a time capsule, I’d hate for people 30 years from now to watch ours and say, “Damn, was anybody interested in fucking?”

More From This Series

- 40 Erotic Thrillers You Can Stream Right Now

- The World Wasn’t Ready for Body Double

- Margaret Qualley and Christopher Abbott on Their Dominatrix Thriller