This article was featured in One Great Story, New YorkÔÇÖs reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

The first thing I ask David Cronenberg about are the abdomens. The Canadian writer-director, whoÔÇÖs been described as the ÔÇ£Godfather of Body HorrorÔÇØ by some and ÔÇ£beyond the bounds of depravityÔÇØ by others, has made nearly two dozen movies since 1975. By my count, almost half of them feature somebody reaching into their own stomach cavity to pull out an object, shoving objects into their stomach, reacting in abject shock as something explodes forth from their stomach, or having their stomach torn open and emptied by a malevolent entity. In his latest film, Crimes of the Future, which premiered at Cannes and hits theaters June 3, the stomachs are the whole point: The movie takes place in a dystopian near future where everyone is doing surgery on each other for fun, sensually slicing into each otherÔÇÖs torsos to gaze at, lick, and sometimes yank out the organs therein.

When I meet the 79-year-old director on the patio of a French hotel room the day before the filmÔÇÖs festival premiere, I want to know: What happened to his own body to make him so obsessed with stomachs?

ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve had a couple of hernia operations,ÔÇØ he says from behind a pair of sunglasses that match his head-to-toe black outfit, topped off with a baseball hat for his 1999 film Existenz, about plugging the other side of oneÔÇÖs torso into a video-game console. ÔÇ£Nothing more exotic than that, IÔÇÖm afraid.ÔÇØ He apologizes for the sunglasses ÔÇö heÔÇÖs ÔÇ£finding it very bright.ÔÇØ He got them for free on an earlier trip to Cannes but wasnÔÇÖt able to wear them until recently, when, as he puts it, he had ÔÇ£plastic lensesÔÇØ put into his eyes to replace his need for a prescription. (ÔÇ£I am bionic for sureÔÇØ). For Cronenberg, a man who says he has ÔÇ£never gone to therapyÔÇØ because ÔÇ£my parents were really sweet,ÔÇØ the anatomical fixation is mostly an issue of logistics. ÔÇ£If you want to get into somebodyÔÇÖs heart, you have to crack their ribs apart and everything,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£If you want to get into somebodyÔÇÖs body, this is where you would naturally go.ÔÇØ

Cronenberg has been poking and prodding and exploding and decapitating and mutating the human form for the entirety of his film career, which has somehow still brought him to the genre-shy Festival de Cannes six times. On his first go-round, in 1996, Cronenberg scandalized the entire Croisette with Crash, an adaptation of J.ÔÇëG. BallardÔÇÖs 1973 novel about people who are sexually aroused by car accidents. People walked out in droves; critics called him ÔÇ£perverseÔÇØ and ÔÇ£sexually deviantÔÇØ; the Cannes jury, split on the filmÔÇÖs merits and egged on by president Francis Ford Coppola, refused to award him the Palme dÔÇÖOr and instead gave him a Special Jury Prize ÔÇ£for originality, for daring and for audacity,ÔÇØ which still manages to sound like a neg. When I tentatively bring up the whole ordeal, assuming it might be a sore spot, Cronenberg laughs like someone recalling a wild night out in college. ÔÇ£There were 500 crazed journalists wanting to kill me and saying I should be put in jail and all my cast should be executed,ÔÇØ he says, sipping his cappuccino. ÔÇ£I was thrilled!ÔÇØ

In his successive four trips to Cannes ÔÇö for 2002ÔÇÖs Spider, 2005ÔÇÖs A History of Violence, 2012ÔÇÖs Cosmopolis, and 2014ÔÇÖs Maps to the Stars, all of which veered away from the overt body horror of his earlier work in favor of subjects slightly more palatable to the mainstream ÔÇö Cronenberg received positive-to-mixed reviews and varyingly lengthy standing ovations, but he has still never won the top prize. (Something everyone else seems to care about more than Cronenberg: ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve won enough prizes.ÔÇØ) After Maps, he took eight years off from filmmaking in what some believed was an official retirement from the business. Cronenberg insists it wasnÔÇÖt that serious. ÔÇ£I didnÔÇÖt really say that,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£I said, ÔÇÿIf Maps to the Stars is my last movie, itÔÇÖll be okay.ÔÇÖ Some fans got very upset by that, which is very sweet.ÔÇØ

In those eight years, he tried his hand at writing a novel (Consumed) because it was less of a ÔÇ£hassleÔÇØ than filmmaking (ÔÇ£You donÔÇÖt have to finance itÔÇØ). He lost his wife of 43 years and for a while ÔÇ£didnÔÇÖt have the heartÔÇØ for directing. When his longtime producer Robert Lantos called him up a few years ago and asked him to revisit a script heÔÇÖd written in 1998, he decided to take on One Last Job (which has, in classic Cronenbergian fashion, now mutated into Three Last Jobs: HeÔÇÖs shopping a new script, The Shrouds, at the Cannes marketplace and tells me he plans to adapt his novel). Cronenberg was surprised the old script still felt relevant, perhaps even more so than it had when heÔÇÖd shoved it back into a drawer in the ÔÇÖ90s. Ultimately, he says, he didnÔÇÖt change a single word in Crimes of the FutureÔÇÖs script. (The only thing that changed was the title ÔÇö originally called Painkillers, he swapped it for the name of an underground short feature he made in the 1970s.) ItÔÇÖs about a near future where humans start inexplicably growing new organs, become unable to feel pain or develop infections, and evolve to digest microplastics (how did he know about the microplastics?). They react to these shocking evolutionary shifts in various ways: The government tries to suppress the organ growths; everyday people get their kicks by performing amateur surgery on each other in the streets. Longtime Cronenberg collaborator Mortenson stars as Saul Tenser, a performance artist who, along with his partner Caprice (Lea Seydoux), removes his prolifically sprouting organs on public stages while slowly realizing it may be better to give in to his bodyÔÇÖs transformations.

The film has been described as an allegory about the nature of art and climate change; the cast says it functions on another level: as a metaphor for CronenbergÔÇÖs own career, about a man excavating himself in order to make deeply personal art. Mortenson calls it CronenbergÔÇÖs ÔÇ£most autobiographical film.ÔÇØ Kristen Stewart, who plays a government agent tasked with tracking and suppressing the worldÔÇÖs rapidly increasing supply of new organs, said, ÔÇ£HeÔÇÖs excavating these organs and coughing them up, and heÔÇÖs like, How long am I going to be able to do this?ÔÇØ

In the lead-up to the filmÔÇÖs festival -premiere, much of its early press focused on whether the filmÔÇÖs more graphic sequences ÔÇö which include a child murder and a public autopsy, a dude whoÔÇÖs sewn a bunch of ears all over his body, Stewart shoving her hands down MortensonÔÇÖs throat, and more glossy organs than a megachurch ÔÇö would cause Cannes to pull another Crash with the French fainting in droves before standing back up and calling Cronenberg a psycho perv. But with the recent 4K Criterion release of Crash certifying its status as a misunderstood cult classic, and last yearÔÇÖs Palme dÔÇÖOr winner Julia Ducournau openly citing Cronenberg as an inspiration for her car-sex masterpiece Titane, and the fact that the world has gotten 600 percent more unhinged in the time since CrashÔÇÖs release, is it possible that Cannes is ready to celebrate him instead of threaten to imprison him? ÔÇ£I think people have caught up in a sense with Cronenberg,ÔÇØ Mortenson says. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt know if Titane having won last year is a benefit, or if itÔÇÖs like, Okay, we did that once. We donÔÇÖt have to do that now for a few years.ÔÇØ

For his part, Cronenberg is relatively blas├®. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖd rather they didnÔÇÖt walk out, because I didnÔÇÖt make it for people to walk out. But if they feel that way? IÔÇÖve had it happen before. It didnÔÇÖt kill me.ÔÇØ

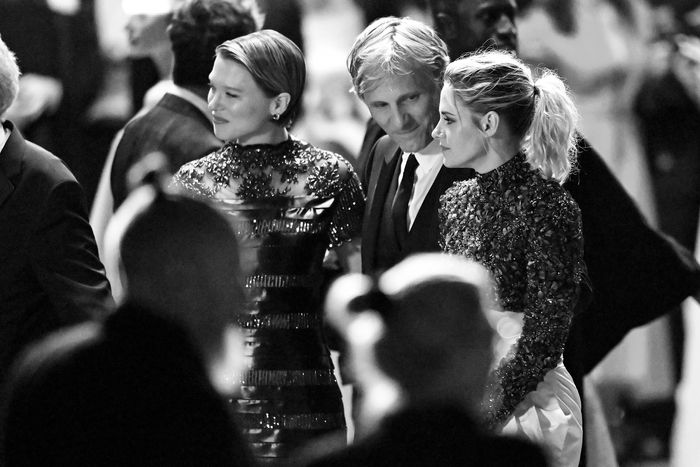

At the premiere, Cronenberg and his cast look blissful on the carpet. The director, in a pair of white gogglelike sunglasses to block the camera flashes, sips a Perrier. Stewart is sporting a crop top and high-waisted skirt that frame the exact part of her Cronenberg most loves to filmically desecrate. Later, she tells me that the shirt was so tight that it hurt her. ÔÇ£I walked out with these red, like, fuckinÔÇÖ lacerations on my stomach. It was very in keeping with the movie,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£I cut myself open.ÔÇØ

During the movie, groups of people walk out every ten minutes or so, usually when someone onscreen is moaning sensually as another character probes their innards. Most of the audience seems rapt, though two people next to me fall asleep. As the credits roll, the theater is silent and itÔÇÖs unclear whether itÔÇÖs in reverence or disgust. ÔÇ£I was like, Ooh, people donÔÇÖt know how to feel,ÔÇØ Stewart tells me later. ÔÇ£They donÔÇÖt know if they should clap or not. I felt like it was the fuckinÔÇÖ Will Smith moment where everyone was like, Yes? No? No. Okay, actually no! Like, do people have to look to their left and right to see if people like it before they clap?ÔÇØ

Then the lights go up and Cronenberg and his cast receive a seven-minute standing ovation, which, in Cannesspeak, means, ÔÇ£We basically liked it, we think.ÔÇØ A cameraman inside the theater thrusts a mic at Cronenberg and projects his face onto the screen. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm very touched by your response,ÔÇØ he says to the still-applauding crowd. ÔÇ£I hope youÔÇÖre not kidding. I hope you mean it.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£I wouldnÔÇÖt see this movie on purpose in my life,ÔÇØ I hear one French woman say as we all shuffle out of the Lumi├¿re. ÔÇ£But clearly there are very big fans of him here who are freaking out. There were thousands of people trying to get tickets to the screening and couldnÔÇÖt.ÔÇØ (SheÔÇÖs referring to the hordes of teens waiting outside the theater for a glimpse at Cronenberg.) Another woman is animatedly trying to explain the plot of the film to her boyfriend: ÔÇ£So surgery is the new sex but itÔÇÖs also art made from suffering, and there is a doctor who makes zippers into your body.ÔÇØ

At the after-party, the consensus in the room is that the screening went well. Reviews pop up as the night goes on with many critics hailing it as a thrilling return to Cronenbergian body-horror form; the New York TimesÔÇÖ Manohla Dargis calls it ÔÇ£easily the spookiest, most original and intellectually provoking selection that IÔÇÖve seen here so far.ÔÇØ Nobody calls for CronenbergÔÇÖs head or even his kidney. ÔÇ£I know Cannes was a tough crowd, but it seemed okay?ÔÇØ says Scott Speedman, who plays a renegade railing against the governmentÔÇÖs attempts to suppress the shifts in human evolution. Stewart, now in a crop top and jeans, shuffles playfully to Missy Elliott alongside Ducournau, who popped in for the premiere and the festivalÔÇÖs 75th anniversary party. Seydoux sips ros├® in a corner.

Cronenberg is seated quietly on a couch away from much of the hullabaloo. ÔÇ£I am trying to relax,ÔÇØ he says. I notice that every food item on offer looks like itÔÇÖs been designed to resemble a pile of organs: vitello tonnato draped heavily over a cracker, little bowls of unidentifiable mushy meats and vegetables stacked on top of each other.

I ask the director if the food is meant to evoke the filmÔÇÖs bodily visuals. He looks me right in the eye. ÔÇ£Are you crazy?ÔÇØ he asks.

The morning after, at the filmÔÇÖs 10:30 press conference, Cronenberg is introduced as ÔÇ£a gentleman who has the word cinema tattooed on his organs.ÔÇØ HeÔÇÖs clearly feeling spunky and irreverent ÔÇö he jokes about how Mortenson is his eternal slave. When heÔÇÖs asked a muddled question about ÔÇ£aging and death,ÔÇØ replies, ÔÇ£That was such a downer of a question.ÔÇØ

At the end of the conference, members of the audience shove their way to the front of the room for autographs and photos, desperate to bring home a tangible chunk of their heroes. The press conference host pleads with them: ÔÇ£Just donÔÇÖt lie on the table.ÔÇØ Cronenberg, Stewart, and Seydoux all make a mad dash for the exit, but Mortenson stays, patiently acquiescing to his screaming fans. A few minutes later, both of us are sitting on a nearby rooftop, and I ask him why he didnÔÇÖt leave with his co-stars. He takes a long pull on a hand-rolled cigarette, staring off into the middle distance. ÔÇ£WhatÔÇÖs the harm in stopping and talking if you have time to do it?ÔÇØ he says. Seydoux, on another couch a half-hour later, is a bit more philosophical about the whole thing. ÔÇ£I was thinking when I was watching the film last night, Oh, this is exactly what weÔÇÖre living right now, in Cannes, with all the cameras,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£I give something of myself thatÔÇÖs very intimate, and theyÔÇØ ÔÇö fans ÔÇö ÔÇ£do whatever they want.ÔÇØ

I find Cronenberg again, whoÔÇÖs sitting near a sunny spot on a patio, soaking in the moment. ÔÇ£We keep trying to suppress you, and you keep popping up!ÔÇØ he says by way of greeting. He tells me heÔÇÖs feeling buoyed by the fact that the audience ÔÇ£received the film the way I sent it out.ÔÇØ What he means, I think, is that rather than fixate on the shiny spleens of it all, Cannes viewers saw the film for what it was ÔÇö a tender, probing (in more ways than one), and essentially tragic exploration of the human raceÔÇÖs current predicament: Do we fear and fight the rapidly changing dark future weÔÇÖve set up for ourselves, or do we try to embrace the world weÔÇÖve broken and change ourselves instead? ÔÇ£The audience really, I think, have felt it in its complexity,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£It hasnÔÇÖt hit them as a horror film or even a sci-fi film or a noir film, because they also talk about the melancholy and the sadness of parts of it. And thatÔÇÖs really quite sweet. ItÔÇÖs understood and felt.ÔÇØ

More From Cannes 2022

- How to Find Hope and Destroy It

- Charlbi Dean, Star of Palme dÔÇÖOr Winner Triangle of Sadness, Dead at 32

- Freak Out! Over New Bowie Footage in Moonage Daydream