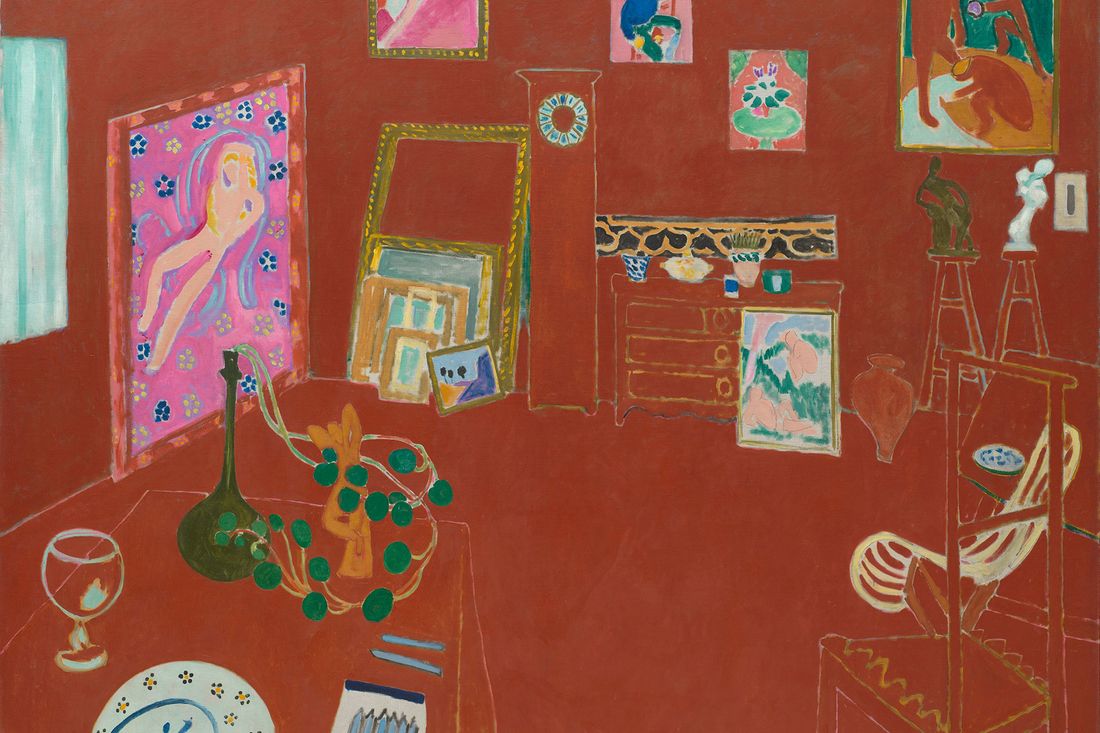

Henri Matisse’s The Red Studio is among the most gorgeous lodestars in all of modernism. Completed in 1911, it depicts the inner sanctum of his studio in the Paris suburbs. It is a miracle in red, a coral-colored planet, its flat, near-monochrome treatment now a mainstay of contemporary art. In this enclosed garden, we see decorative ceramics, drawing tools, a leafy nasturtium, an empty wine glass, vases, and a grandfather clock with no hands because, of course, time ceases to exist when artists are in creative flow. Red Studio reminds us that a studio is at once laboratory, shelter from the storm, personal cathedral, and star nursery where brilliant things are formed by unknown forces and internal pressures.

The studio is filled with paintings stacked in rows and haphazardly hung. Art lovers will spy a handful of masterpieces on the walls. If this painting were turned into a small museum, it would be one of the best there is of early modernism. This is what MoMA has attempted to pull off in a ravishingly compact show that showcases not only Matisse’s revelation in red but also six paintings depicted in Red Studio, three sculptures, and a wonderful ceramic plate. You look around at this art-historical reunion and a long-gone world becomes young again. It goes off inside you like a depth charge.

“Matisse: The Red Studio” does a lot in a little space and reminds us that blockbusters can come in small packages — in this case, two main galleries of art. (Although don’t miss the short video on the conservation of this painting. It is a lesson in curatorial care and discovery.) In this concise show, we can ponder things longer, linger, make connections, see how one work might grow out of another without feeling overwhelmed, swamped by numbers, and exhausted at the end. More institutions should consider this scale, the scale at which the work was made. We see how, in an incredibly condensed period of time, an artist can traverse universes and touch down in places unexpected. We witness an artist not only inventing and reinventing himself but reinventing art history as he does so. In these little spaces, you can almost hear these mighty engines roar.

First the nudes, which were once considered ugly. You can see why. Nothing like these had ever existed before. Matisse was modeling shape to follow an artist’s imagination, infused by the radicality of African sculpture and its elongated bodies. He’s on fire with the ways the recently deceased Cézanne had turned figures into twisting coastlines with arms and legs. This is the aesthetic cyclotron Matisse is spinning in these few works. This is what change looks like in real time.

Here it is in the teeny 1906–7 terra-cotta Upright Nude With Arched Back (the work I’d most want to own if our cat wouldn’t surely destroy it). It is reminiscent of something voluptuously Neolithic, a fundamental female form, but it is also on the verge of flying apart and into space. The same historical continuum is in Young Sailor II, a 1906 portrait of a boy in a chair in a peach-colored room. At first it looks like a folk painting. Look closer: The pictorial sophistication is off the charts. We see a figure turning toward and away from us at the same time, relaxed but ready to pounce, seen from below and above simultaneously. He touches his thigh, rests his elbow on the invisible back of the chair, and stares us with a come-hither look. We are his — and Matisse’s.

There’s no evidence to support this but I fancy the splayed, flagrant Nude With a White Scarf (1909) is taken almost directly from the second nude on the left of Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, finished two years before. Picasso’s arched leg and knee are here, as is the arm raised over the head to fully expose the breasts and twisting torso. The biggest difference is that Picasso’s woman seems caught between lying down and standing, while Matisse has her lean back and makes her living flesh, not an angular monster.

Still, you see an artist turning away from the “real” world of space, structure, color, narrative, surface, and composition — an artist bound for new beauty, willing to risk it all. “Matisse: The Red Studio” shows us an artist picturing works he’d already created and breathing second lives into them, a metaphor for how the work of all artists grows from that which they made or saw before. Matisse was 42 when he finished The Red Studio, approaching one of the many heights of his optical abilities. But Sergei Shchukin, the Russian collector who commissioned the painting with two others, didn’t see it that way, rejecting its weird spatial architectonics out of hand. MoMA displays a plaintive letter written by Matisse in which he asserts, “The painting is surprising at first. It is obviously new.” To no avail. Shchukin quickly turns him down again, going on to write of the weather in Moscow.

He just couldn’t see it. The perspective of Red Studio was not the “Japonisme” of Impressionism, or Cézanne’s angling visual shifts, or Cubism’s 360-degree all-at-once vision — it was altogether alien, the product of years of brutal experimentation. I’m not sure we recognize just how revolutionary and “obviously new” this painting is even today.

Matisse was the avant-garde master of Fauvism, the disparaging name (from les fauves, meaning “wild beasts”) given by critics disturbed by the movement’s abstract forms, destabilized spaces, and juicy paint. All this started changing when the older Frenchman paid a visit to Picasso’s studio. There he saw the wrecking-ball shot fired over the bow of western painting known as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Matisse knew that, with this painting, the aesthetic earth had shifted on its axis and he had to respond at once.

Their rivalry was one of the most productive and gut-wrenching give-and-takes in art history. Picasso was a total mindfuck whose Oedipal wars with older artists never ended, and he could produce so much so quickly that he was doing most of the taking, while Matisse kept pace, following his own path and redefining what painting might be. This beautiful duel set off numerous atom bombs of art: From Matisse alone, Portrait of Mlle Yvonne Landsberg, View of Notre-Dame, Bathers With a Turtle, Dance (I), not to mention the four huge, almost Mesopotamian bronze-back sculptures. At first, Paris was spellbound. Soon, however, sides were taken, and Matisse was found wanting.

In 1913, art students burned the work of Matisse in effigy, including Le Luxe II. Gertrude and Leo Stein, taste-masking patrons of the Parisian scene, bought fewer Matisses and doubled down on Picasso, who charged that Cubism wanted to “make sure nothing is ever decorative again.” He meant Matisse. In Apollinaire’s sympathetic words, Matisse was “one of today’s most disparaged painters.” Critics attacked him as old, tame, retired. After Matisse generously introduced Shchukin to Picasso, the Russian became an avid collector of the Spaniard. Soon thereafter, Shchukin rejected two of Matisse’s greatest paintings, Dance (II) and Music — before changing his mind, this time.

In 1917, Matisse finally left the Parisian fray for the south of France. Here is the setting for his next incredible campaign into painting. One work that always makes me cry seems the capstone of his time in Paris: Interior With a Violin, 1918. We see a room with one wooden shutter open. It blasts beautiful light, a view of the Mediterranean, and a glimpse of a palm frond. To the left of the window is an armchair. Forget Picasso’s fractured guitars — here’s a violin in an open case. You feel Matisse breathing new air, about to remove the instrument and play it, away from the Paris rat race, on his own again, about to effect a new type of visual music that will arrive with his odalisques.

Now let’s look at The Red Studio. Here is an origami of sundering simplicity, setting new geometric ordinances that insist the highly abstract world inside his painting is a real world, imagined or not. Originally, this painting wasn’t the flaring sunspot it is now. The floor was pink, the walls were blue, and the furnishings were ochre. There were narrow slats that may have indicated wood panelling. Matisse abandoned that approach in search of a new dimensionality different from anything being painted at the time. He created the unifying field of color that, as painter Carroll Dunham put it, “eliminated a lot of static, variables, and established a space, surface, and framework to go crazy in.” The resulting studio is both illusionistic and tangible, rational and insane, almost like a cave painting.

A completely flat ground recedes here, comes forward there. On the left is a tantalizing glimpse of blue outside a window. There are corners but no shadows, and the objects are as stable as Cézanne’s apples on tilted tables, yet vibrating just a little. Matisse’s lines are faint, nearly nonexistent, etched into the blank areas with smudging tools. You become ultraconscious of every mark and move on the surface. You can almost reconstruct how this work came into being, what’s on top of what. He leaves all his painterly tracks showing. This places you in the artist’s mind as well. It’s weird but astonishing and makes you feel really smart for being able to see this work of genius like a true pro.

Matisse is not better than Picasso or the other way around. But Matisse is an opposite of Picasso. His compositions aren’t held tightly within the borders of the painting, as Picasso’s always are. Elbows bleed off the edges of a Matisse. Serpentine lines disappear then reappear on the canvas, as if the surface were folded like a curtain yet forever inexorably flat. The “obviously new” reality that the Paris of that time rejected is contained in the space and place that is The Red Studio. Here is a room, a home away from home, where beginnings happen, where the bottom falls out, the walls dissolve, time goes away, and we behold new ways to see, feel, and know the world.