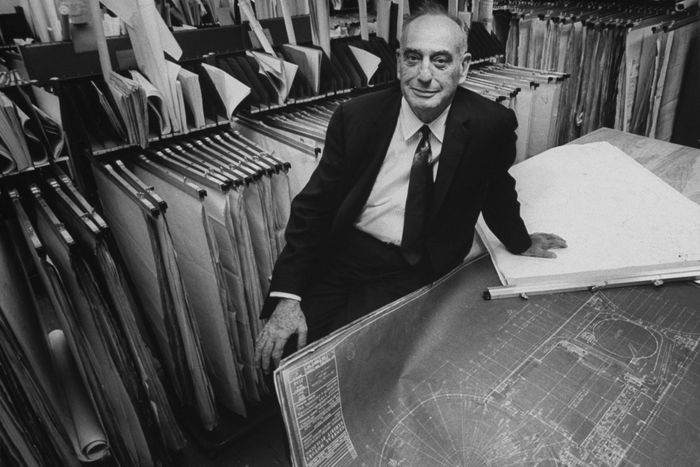

Can you make ripping drama out of urban planning? In theory, sure. The potential for finding narrative power in this square subject lies in adjusting focus from concrete and steel to people and communities, looking for the beneficiaries and victims. That’s clearly David Hare’s intent in Straight Line Crazy, his new play — running at the appropriately named Bridge Theatre in London — about the career of Robert Moses, the visionary and monstrous master planner of mid-century New York City and Long Island. Moses was the man who tore down big swaths of poor (and especially nonwhite) neighborhoods to hack highways through the city, shunting residents into apartment complexes that were drab when new and got worse from there. In The Power Broker, Robert Caro’s immense and definitive Moses biography, the human aspect of all that social and political and physical engineering gradually rises up off the page, building a portrait of a man so confident in his own opinion and so entrenched in his own power that no one can stop him. He lived, he said, to serve the people; nonetheless, he didn’t appreciate actual people, or what they wanted, very much.

Straight Line Crazy is not quite The Power Broker: The Play, but you can’t do anything with Moses unless you’ve absorbed Caro’s book, and Hare clearly has. (You can buy a copy in the lobby, though it’s missing from the credits.) The Carovian framing of the man appears again and again onstage: Moses’s time spent swimming; his canny manipulation of public officials; his first wife’s alcoholism; his increasing disregard for any opinion beyond his own and, of course, those infamous, insidious low bridges over the parkways.

Ralph Fiennes is impressive to watch as he channels some of the brawn and vocal gravel of the man. It’s a two-act play, the second taking place about three decades after the first, and the intermission hair-and-makeup modifications are minimal at most. Fiennes mostly just adjusts his stance to read older and heavier, and that suffices to age him. In the course of the first act, set in 1926, he goes toe to toe with a Vanderbilt and Governor Al Smith (Danny Webb), and hornswoggles them both to get what he wants, as his deputies scurry and Jane Jacobs (Helen Schlesinger, looking uncannily like Jacobs) lurks in the future. By the second half, it’s 1955 and he’s an emperor of all he surveys — except Jacobs at her community-action meetings and one young Black architect in Moses’s office (Alisha Bailey, doing well in a somewhat one-dimensional role) who speaks up to him about what he has done to the Bronx neighborhood where her family lived. We’re meant to see that the world has changed and his ideas have not, which is a reasonable enough reading of where Moses went wrong.

It takes a lot of explaining to get everyone to that point, and therein lies the trouble. On the pages of Caro’s book, the human cost of Moses’s projects builds over time and crests in the last, oh, 400 pages or so. By then a reader is steeped in the mid-century condition of New York City, the economics of the Depression era, the dynamics of the state legislature, housing and transportation policy, and — most of all — the prevailing mindset of the era’s planners. Hare, by contrast, has to do the whole business in two hours onstage, and do it for an audience (particularly in London) that does not know much about, say, the particulars of the Major Deegan Expressway. So what the characters do, in scene after scene, is stand and talk past one another. Moses has a plan; one of his deputies challenges him on it, explicating for several paragraphs why the boss might be mistaken. Then Moses explains back at her, firmly, why he isn’t.

Let’s set aside that this rather balanced character portrait is an absurd characterization. Robert Moses, a former Yale debate champion, was known for his ferocity and intransigence in the face of a challenge. If you so much as tried to declaim to the real man about why some aspect of his plans was flawed, he would immediately outflank every angle of your argument (which he’d most likely figured out how to dispatch with a sneer, decades earlier), and then perhaps eject you from the building and ruin your career. He stormed out of meetings when someone disagreed with him. He outmaneuvered and steamrollered several decades’ worth of New York governors and New York City mayors, including Franklin Roosevelt. A 25-year-old assistant — particularly a woman, especially a woman of color — was not going to talk him out of anything.

Even if you accept all that as dramaturgical necessity, what we end up with here is a very monologue-driven, very static play. (And it isn’t necessary. It is entirely possible to pack this much nerdy exposition into a script and have it remain thrilling; the movie Apollo 13 does it perfectly, for example.) Here, there’s a lot of pointing at dotted lines on maps, including one giant-size one that’s unfurled like a carpet, allowing Moses literally to stride at will across the New York landscape he has resculpted. Somehow it makes him seem smaller instead of bigger. As he passionately explicates the need for the three cross-Manhattan expressways that he is demanding, everyone stands there, and it comes off as pleading rather than the stance of a Napoleon or a Caesar. When a longtime aide essentially calls him a racist, he meets the charge almost blandly.

Is it a hometown quibble to say that the show also flubs some details about New York? An aide in Moses’s offices refers to “the Fashion District” rather than the Garment District. (Maybe you’d hear that today, but in 1926 no way.) Governor Al Smith was legendary for his distinctive brown derby — as much a signature in its day as Steve Jobs’s black turtleneck was in his — and here he wears a soft dark felt fedora. Jacobs’s Greenwich Village meetings, organized to fight off the highway Moses wanted to cut through Washington Square, display significant racial diversity, surely meant to heighten the contrast with Moses’s white supremacy. The real mid-century Village was ethnically mixed but very white. The historical texture is just a little bit wrong, a little too often.

Speaking of Al Smith: If you set aside that hat, Webb is the best thing in the show. Smith himself was a mouthy public character, a Lower East Side slum kid who became an absolutely beloved four-term governor (and lost the presidency, in a landslide, in 1928, largely because he was a Catholic). Hare and Webb portray him super-broadly, drawing big laughs as he curses like a longshoreman, banters with Moses, and tosses back a couple of glasses of illicit bourbon. The play vibrates to life when he’s onstage, not because it’s any less talky but because Straight Line Crazy is, if only for those 20 minutes or so, inhabited not by plans for the people but a couple of actual ones.

Straight Line Crazy is at the Bridge Theatre in London through June 18.