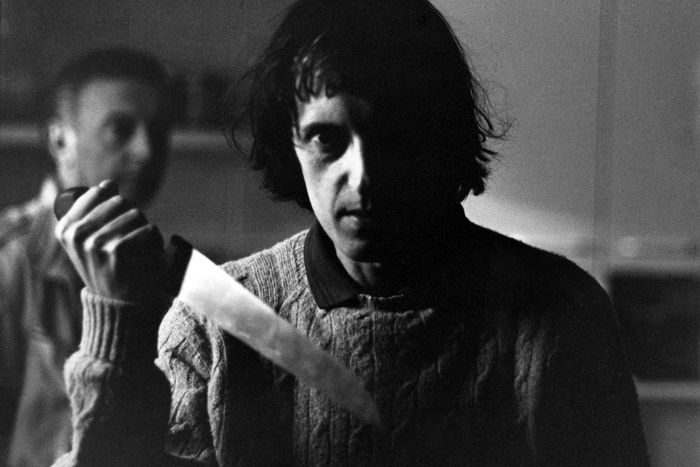

Italian horror filmmaker Dario Argento is having one hell of a year, both on and in front of the big screen. Argento’s not normally an actor, but in late April, American audiences saw Argento deliver a chilling performance opposite co-lead Françoise Lebrun in Vortex, Gaspar Noé’s harrowing split-screen drama about aging and dementia. And starting this week, Film at Lincoln Center celebrates the Italian Hitchcock’s vital directorial work with “Beware Dario Argento,” a retrospective featuring 17 new restorations of Argento’s movies (courtesy of the historic Roman film studio Cinecittà).

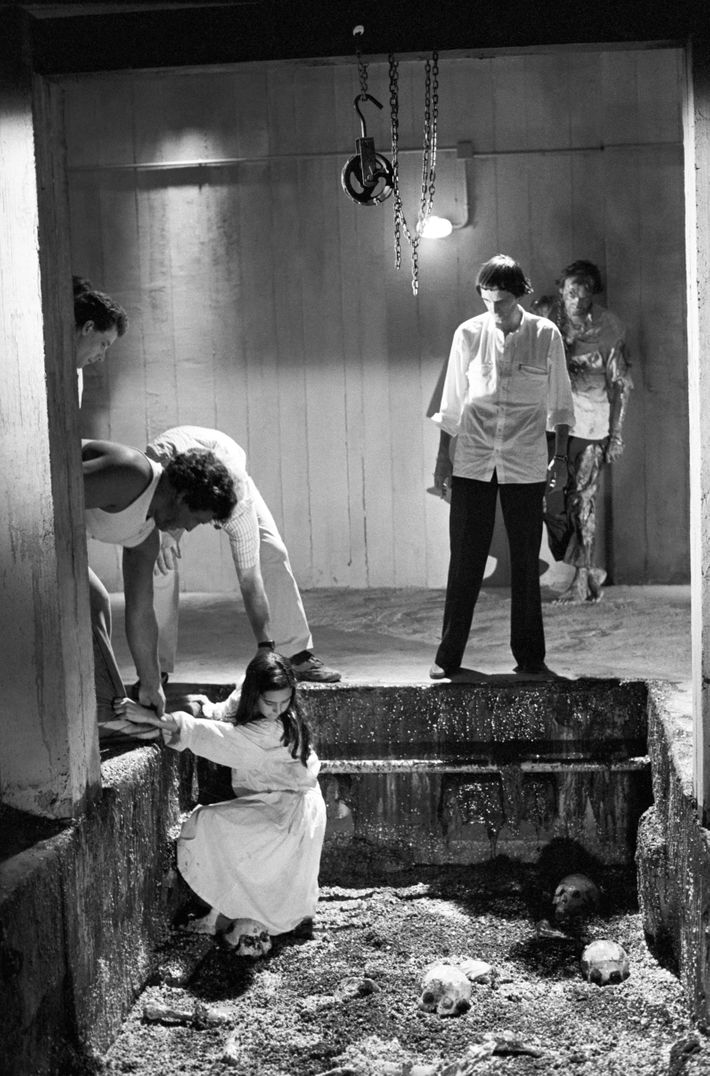

“Beware Dario Argento” includes an expansive selection of Argento’s movies, from his formative and lurid giallo thrillers (Bird With the Crystal Plumage, Deep Red) to surreal horror classics like Suspiria and Opera. (Full disclosure: I wrote the program notes for the series.) Film at Lincoln Center’s survey also features Argento’s most recent movie, Dark Glasses, a compelling Rome-set thriller that follows a blind sex worker (Ilenia Pastorelli) and a young orphan (Xinyu Zhang) as they’re both stalked by a mysterious killer.

Vulture spoke with Argento, with the diligent assistance of translator Michael Moore (not that one), about acting in Vortex as well as working with actors like his daughter Asia Argento and his late ex-wife Daria Nicolodi, as well as a gaggle of rowdy cats and a very nervous chimpanzee.

Your performance in Vortex is tremendous and a rare acting role for you. Noé told us that Vortex’s script was only ten pages long and without any dialogue. How did you shape your character?

I didn’t really shape the character. I tried to play myself … let me go back a little bit. When Gaspar came to my house in Rome to ask me if I would be in the movie, my immediate answer was “No.” I didn’t feel like being an actor. But he spent the entire day at my house. He wouldn’t leave. And then he said the magic words, that the entire film would be improvised. That word in particular, improvised, rang a bell. After all, I am a child of Italian neorealism, so I am sort of accustomed to the practice of improvisation. Rather than use professional actors, the neorealists worked with the average man on the street, people who spoke with their own accents and who came up with their own lines. That interested me, so I thought, Yes, I could do something improvised.

Still, this character — he has no name in the movie — had to be somewhat similar to my own. He’s a film critic, just like I was before I became a director. And in the movie, he wrote an essay, a book on the relationship between cinema and dreams. I have also written an essay on cinema and dreams.

That all being said, I was not interested in being an actor. I also don’t feel like what I did was acting — I played myself. What you see in the film is me telling my story.

You once said that actors are one part of the “cinematic mosaic.” As a director, how would you describe the way you work with actors?

I ask the actors to be themselves. And every evening, before they leave the set, I repeat the same thing: For tomorrow’s part, which you have in front of you, I want you to invent something. Something that belongs to you. Something personal. Something intimate. I want you to think of something about yourself and bring that to me. In this way, the actor enters more deeply into the film. And then the film belongs to them as well, since they’re putting an important part of themselves into it.

The tone and humor of your directorial work can be very particular, as in Deep Red, where even the death scenes feel surreal. Deep Red also features some relatively straightforward comic relief, like the coffee-shop phone call or the arm-wrestling scene. I wondered how you worked with Daria Nicolodi and David Hemmings on performing in these humorous scenes.

You know, I didn’t give them many instructions. Those scenes came out as they were written. In terms of humor, I’m inspired by Alfred Hitchcock, who has a lot of humor in his films. I like that kind of British humor; it’s a very refined sort of humor. I want the humor in my movies to be like that, kind of classy. Not the kind of humor that is about a funny line or quip here and there.

You co-wrote Suspiria with Daria Nicolodi. How would you describe working with her?

Daria and I traveled throughout Europe looking to study and to investigate European witchcraft. We went to Germany, Switzerland, France, and Belgium, looking for historic examples. We also tried to meet with witches or people who claimed to be witches. The truth is we never met anyone who claimed that they were a witch, only people who talked about witchcraft. So in my opinion, witches don’t really exist. But there is an interesting culture of witchcraft, and it’s expressed in books and novels and all over the place. There are also houses that are haunted, in a way, and that have an air of witchcraft about them, especially in Belgium and Brussels. We saw a little of that during our journey before making Suspiria.

In your “Three Mothers” trilogy of Suspiria, Inferno, and later Mother of Tears, witchcraft is a very real, if also very dreamy, conspiracy. So it’s interesting to hear you say that you don’t believe in witchcraft. Did your attitude towards those movies or their witchy subjects change over the years?

It wasn’t really a change of heart or belief. I let my imagination guide my research for all three movies, which are all different. Suspiria is inspired by supposedly true stories of witches, as well as other books and writing. Inferno is much more enigmatic; it leaves a lot up to interpretation. I made that movie for 20th Century Fox, and when I finished it, I watched it in Los Angeles with Sherry Lansing, the president of Fox. She told me that she understood nothing about the movie. “What does this mean? And what does that mean? I don’t get it. Why didn’t you explain this better?”

“You know, I’d hoped that the audience would come up with their own explanations,” I told her. That’s the secret of the film. That’s the kind of alchemy that a film should have, and Inferno’s a very alchemical film. Still, Sherry Lansing didn’t like Inferno, and as a result, it was never theatrically released in the United States. It was a big success in England and France, though.

The third film, Mother of Tears, is a very violent film because the witches in that movie are more ferocious and more numerous than they were in the previous movies.

You’re talking about how you conceived these films as a scenarist, but as a director, getting what’s in your head onto the screen requires some negotiating. So if you’ll permit a silly question: What can you tell us about the Inferno scene where Daria Nicolodi gets attacked by a herd of cats? How did you get what you needed for that scene?

That was a particularly difficult scene, for which I worked with Nicolodi and her body double. The body double’s face was covered with a rubber mask that went all the way down to her bust so that way, the cats’ claws wouldn’t sink into her skin. We threw the cats first at Daria and then at her body double. That’s a very violent and a very shocking scene … I didn’t realize it was gonna be quite so hard to make.

You got great results from another very particular animal performer in Phenomena: Tanga the chimpanzee. That was not an easy collaboration for Tanga’s co-star, Jennifer Connelly, though she has a big smile on her face in the film’s last scene when her character embraces Tanga. How difficult was it to work with Tanga, and how did you and Connelly get that great final embrace? Was that scene shot before you ran into trouble later on…or was that just really good acting?

That was the last scene we shot, which, in hindsight, was kind of risky. I don’t know if you know this, but chimpanzees are incredibly strong. I had to use a body double for that scene as well, for Jennifer, because she and the chimpanzee fought a lot. The chimp would grab her arm and Jennifer would scream and become very agitated. The chimp also became a little agitated, but I was lucky. I spoke to the chimpanzee in Italian when I was preparing for a scene where the chimp has to peer through Venetian blinds. I also brought the chimp to the window with the Venetian blinds and showed her, with my hands, what I wanted her to do, and how she was supposed to tear apart the Venetian blinds, and then just break them.

The chimp looked at me very seriously. When we began the shoot, I put her in place and she did exactly what I had shown her. She made up for her good behavior the next day. We were shooting a scene near a forest and the chimp escaped. She was missing in action for three days. We had to call in the forest rangers to find her. They knew that the chimp would eventually get hungry, so they placed food around the forest and caught her when she came out to feed.

You’ve also directed your daughter Asia in a few movies, including her fantastic lead performance in The Stendhal Syndrome. In the past, you’ve said that Asia was perfect for the role because it required a “spontaneous,” “nervous,” and very “modern” actress. How did you and she work on getting both her character and her performance where you needed them to go?

Preparing for that performance with Asia was really tough. She plays Anna, a very disturbed person who doesn’t realize how disturbed she is until she’s pursued by a sexual maniac. So when Anna realizes how disturbed she is, she first cuts her hair. It’s initially rather long, but she cuts it really short, just like a boy. Then later on, Anna becomes a blonde by putting on a blonde wig.

In order to prepare for this part, the two of us went to a very famous psychoanalyst named Graziella Magherini, the author of an essay on the Stendhal Syndrome. We talked with Magherini about how she, as a psycho-analyst, understood scenes from our movie. Like when Anna sees Pieter Bruegel’s painting, “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” and fantasizes about plunging into the Aegean Sea. Magherini gave us some Freudian insights into scenes like that, as well as Anna’s behavior.

Dark Glasses, your most recent movie, is unlike The Stendhal Syndrome and many of your earlier movies, too, since it follows characters who are defined by stigmatized parts of their overall identity: Ilenia Pastorelli plays a blind sex worker, and Xinyu Zhang plays a Chinese immigrant living in Rome. Normally, your protagonists go looking for repressed or marginalized elements of their past, but in this case, your characters are identified by those qualities. How did you work with Dark Glasses’ co-leads on how they’d represent their respective character-defining backgrounds?

Pastorelli and I read a lot of books about blindness. We also watched many films about the subject. Then the two of us, especially her, met with different blind people to better understand how they moved about, how they behaved, and what they had to say. One person that Pastorelli met had a dog, because her character also has a dog, so we wanted to know how a blind person would work with a seeing-eye dog. That kind of deep research into the reality of blindness was very important, especially for Pastorelli’s understanding of how a blind person manages in life, how they walk through the street, how they meet with people.

There was a lot less work to do with Zhang’s character. We simply wanted him to know how to act like a Chinese boy who’d immigrated to Italy with his family, as he had in real life. So it was very easy to work with Zhang. He was excellent.

Over the course of Dark Glasses, Pastorelli and Zhang’s characters develop a mother/son-like bond. You’ve said in other interviews, that that kind of relationship pushed you to make a better movie and that you learned some things about shooting and working with actresses from observing your own mother at work in her photography studio. How would you say that your mother has inspired you and your work?

My relationship with my mother did inspire me a lot in making movies. She was a well-known photographer of women and when I was a boy, I’d see the different women coming in to her studio to be photographed. She would photograph famous actresses, but also normal women — women of the street, you might say. I often saw how my mom prepared for different shoots, doing the makeup of, for example, Sophia Loren or Claudia Cardinale. My mother would also prepare the lighting in order to highlight certain features of her models’ faces or their bodies. So for years, I was inspired by her in a way that I didn’t at first realize. It wasn’t until I started making movies myself and saw actresses in front of me that I started remembering how my mother had done the lighting and how she had done the makeup. And in the majority of my films, the main characters are either women or girls. Like my daughter. I’ve worked with her on six different films. My mother has been one of my films’ greatest inspirations.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.