Here we are in the decay of empire (again, still); here we are surrounded by glittering micro-cliques, animated by gossip, fueled by takedowns and sanctimony. Here, cancellation is considered a fate worse than death, even though actual death is everywhere, stalking, laughing, coughing in corners. Of course, itÔÇÖs so much easier to pretend that reputation is the thing at risk (not our lungs, our minds, our government); it is sourly gratifying to construct a quasi-professional society around that illusion. In other words, itÔÇÖs 17th-century France. I hope you brought your lace fan.

Not coincidentally, that eraÔÇÖs elegant goad, Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (a.k.a. Moli├¿re), inspired two super-queer plays in New York this week: Circle Jerk, a hypebeast comedy by the Fake Friends collective, and Weekend at BarryÔÇÖs/Lesbian Lighthouse, a whippet-fast farce about life in the New York arts economy. Both plays emulate Moli├¿reÔÇÖs exquisite social critique by filtering it through pop culture, the former show thickly shellacked with TikTok aesthetics, the latter dressed as an ÔÇÖ80s multi-cam sitcom. Like Moli├¿reÔÇÖs satires, these verbally dexterous plays aim their barbs at intellectualism-flavored vacuity, revealing the self-delusion and shallowness of their own courtiersÔÇÖ Instagram followers and pals. Both also crank up the joke velocity to make that criticism easier to take ÔÇö or perhaps to hide their makersÔÇÖ deep melancholy.

The glossier, harder show by far is Circle Jerk, which has had the time to polish itself to a beetle-wing shine. Michael Breslin and Patrick Foley (as well as dramaturgical collaborators Ariel Sibert and Cat Rodr├¡guez) have already gotten onto the 2021 Pulitzer shortlist for the 2020 purely online version, easily one of the best uses of livestreaming during the shutdown. One element of that versionÔÇÖs artistic success was its fusion of technical precision and stage messiness: As the showÔÇÖs three actors doubled and tripled up on parts, they allowed cameras to catch glimpses of Breslin scrambling out of his pants and Foley unzipping an elaborately padded troll costume while dripping with sweat. David BengaliÔÇÖs lighting and video work were flawless, but wigs had to go on fast, facing every which way.

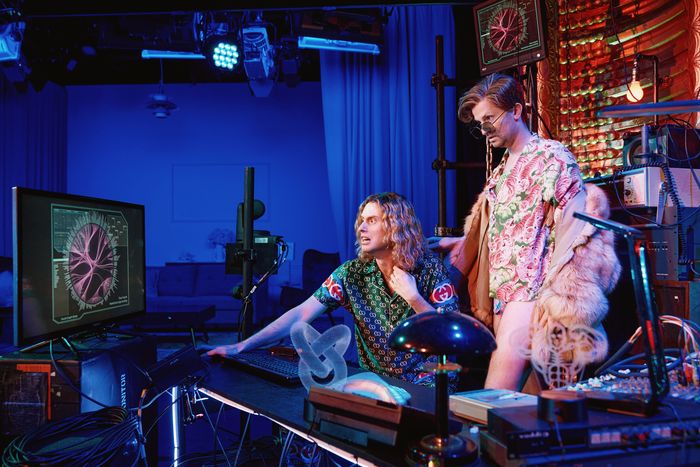

The show in 2022 is only a little changed. (Some references have been updated, and the TikTok choreo is now even tighter.) ItÔÇÖs a hybrid object now, with in-person viewers at the Connelly Theater watching the company film the show for the streaming audience at home. Perks for the in-the-flesh audience include being able to take in all of Stephanie Osin CohenÔÇÖs beautiful stage picture, a Boschian profusion of industrial lights and set pieces and rolling cameras tied together by a snake pit of cables. You also see how hard it is to make this many filthy jokes in a row, how much physical discipline the farce requires, which communicates itself to the audience as a kind of riotous intoxication. A huge television screen hangs overhead, showing us what the digital audience is seeing live ÔÇö two shows for the price of one.

Circle is the story of Jurgen (Foley), a white-supremacist billionaire with a taste for heterosexual genocide, his programming genius Lady Baby Bussy (Breslin), and those they attract to their lair on Gayman Island. Foley also plays the Candide-ish Patrick, a wide-eyed actor willing to abandon his principles to get a boyfriend, and Breslin switches costumes to be the maid Honney (every farce needs a soubrette) and Michael, PatrickÔÇÖs backbiting friend. Couples divide and converge, but Jurgen mostly ignores these poor people since heÔÇÖs bent on global revenge for being exposed as a data miner. He and Bussy turn their digital assistant into the virtual Eva Mar├¡a (Rodr├¡guez), a bot capable of targeting internet users with eerily powerful memes; once weaponized, she drives Jurgen and BussyÔÇÖs chosen victims to suicide, opening up some Lebensraum for the hot, white, and gay.

Most of the textual collaborators (the fifth is the virtuosic director Rory Pelsue) have dramaturgy backgrounds, and the play bristles with as much commentary and marginalia as a grad students copy of Brecht: Theres Jarry-esque bouffon, scraps of Lady Gaga in House of Gucci, structural debts to Charles Ludlam and the Real Housewives franchise. The show is persuasive that social media and pop culture corrupt us while also doling out dopamine rushes to those who recognize  each social-media or pop-culture reference. And because so many of the creators are dramaturges, you just know that theyve talked about the moment when those in-jokes expire, when the text is a dead link to no-longer-shared cultural shibboleths. Someday, like a clowns speech in Shakespeare, this show will require footnotes  and thats going to tickle these creators just where theyre itchy.

As dramaturges, they should be more sensitive to the way their second act drags and the steep drop-off in momentum when they introduce a new character late in the game. The creators draw from media that prioritizes brevity and a short attention span, yet they let their own sequences go on too long. ItÔÇÖs still a custardy, sticky pleasure, though. I donÔÇÖt really care that thereÔÇÖs a whole plotline (ÔÇ£Plot? Was ist das?ÔÇØ ÔÇö Hans-Thies Lehmann, probably) going haywire in the third act because by that point that part of my brain had burned out. So perch the laurel wreath atop of their many, many wigs: The Fake Friends have produced the first, best, most important play made entirely from vibes, which is what you get when you let the internet substitute for atmosphere.

Theres so much thats technically supercharged in Circle Jerk, so many swift attacks and pivots to even meaner attacks, that its a relief to see Jess Barbagallos sweeter, shaggier Weekend at Barrys/Lesbian Lighthouse at Abrons Arts Center. According to the writers note in the script, the evening consists of two plays; if you picture them as TV episodes, the one called Lesbian Lighthouse is a backdoor spinoff pilot using the same characters as Barrys. According to Barbagallo, As the crossover in this play is bizarre and resembles something stolen from an arthouse film, the reader should understand that the genres of each half of the play are intentionally discrete. I went in knowing none of this, and I left the theater knowing  none of this. All I knew was a sense of dazed delight, as if Id surfed onto a channel I didnt know existed but, somehow, starred all the people that I knew.

Down in the Abrons Arts CenterÔÇÖs concrete basement space, the company jogs around a set of white-painted acting cubes ÔÇö the design budget for all of BarryÔÇÖs probably would cover the cost of the Speedos in Jerk. But BarbagalloÔÇÖs wealth lies in his language, a winking, layered, dazzling series of jokes, which land more softly than do Breslin and FoleyÔÇÖs but aim at even closer targets. HereÔÇÖs one of the first rapid-fire exchanges, between BarbagalloÔÇÖs Barry Progue, an artist, writer, and dogwalker, and Helen Hufflekugel, a vaguely European curator who looks all too familiar to anyone making artwork south of 14th Street.

Helen: I loved your piece in Torrents, Barry. ÔÇ£Dispatches From a Sexual IslandÔÇØ is something we passed around, upstairs.

Barry: The title was my editorÔÇÖs idea. She thought ÔÇ£All Hands on DeckÔÇØ was a little quippy.

Helen: Oh, totally, she is correct. The way you compare the theatre of massage parlors to Virginia WoolfÔÇÖs trudge toward the river. It was like a place I very much did not want to be, but I was glad to know someone else had gone there.

ThatÔÇÖs naughty. IÔÇÖm pretty sure I know who that curator is, and Barry is clearly a shifted Barbagallo. But the precision and in-world delicacy of this dialogue mean that I also have a guess about who the editor might be. You think the references in Circle Jerk are insular? Come join me and the rest of the downtown piggies in the warm, muddy wallow of BarryÔÇÖs.

Not that you have to have the key to the drama ├á clef to enjoy it. This short, vivid show is as easy to digest as two sitcom episodes back to back, which is ÔÇö if you factor in a puppet show, a dream sequence that turns into a lo-fi credit sequence, and a sideways jump in reality that reorders some of the personal relationships ÔÇö exactly how heÔÇÖs written it. Using a structure thatÔÇÖs equal parts ThreeÔÇÖs Company, General Hospital, and MoliereÔÇÖs LÔÇÖecole des femmes, Barbagallo introduces us to a zanyÔäó cast of characters: Barry, Helen (Anna Foss Wilson), the young artsy types Biv (L├®oh) and Gin (Dove Murray) who are crashing with Barry as a kind of internship, BarryÔÇÖs roommate Glenn (Ean Sheehy), and neighbor Oto├▒o (Cecilia Gentili). BarryÔÇÖs past romantic exploits are always surfacing ÔÇö he holds a torch for ex Melanie (Maya Sharpe) and shares a dog with Teri (Tanya Marquardt) ÔÇö which would be okay if the art world werenÔÇÖt so damn small.

Barbagallo directed with Chris Giarmo, and their priority was clearly performance: The company provides a rich mix of comic styles, with Barry reeling around as the straight trans man in the center. The storytelling itself gets a bit lost since itÔÇÖs hard to tell when those white blocks are playing BarryÔÇÖs tiny apartment or a tent on a queer beach or a car. Yet everything does snap into focus when Barbagallo is talking about the indignities ÔÇö haha, we can laugh at them, right? ÔÇö of being a maker in New York. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm a patsy trapped in an adolescent netherworld,ÔÇØ he says, coming dangerously close to despair amid all the slapstick and goofiness. Oh, Barry. No. YouÔÇÖre No├½l Coward with a survival job! YouÔÇÖre Champagne in a Solo cup! Whatever you do, donÔÇÖt sell yourself short. WeÔÇÖve had enough of that.

Circle Jerk is at the Connelly Theater through June 25.

Weekend at BarryÔÇÖs/Lesbian Lighthouse is at Abrons Arts Center through June 26.