When the third season of The Wire premiered in September 2004, its resumed focus on the Barksdale drug-dealing organization after 12 episodes spent on the Port of Baltimore might have felt to some fans like a relief. (Time has been kind to The Wire’s second season, but upon its release, the switch away from Avon, Stringer, Bodie, and Omar felt like a betrayal.) David Simon’s return to the corners brought an array of new characters who were, in typical Wire style, not entirely heroes and not entirely villains, and among them was Dennis “Cutty” Wise. Portrayed by Chad L. Coleman, the former Barksdale soldier struggles to reintegrate into society after serving 14 years at the Jessup Correctional Institution. Over seasons three, four, and five, as Cutty moved away from the violence of his nearly mythical nickname and grew into being the more grounded Dennis, the character often served as the series’ moral compass, a responsibility Coleman didn’t take lightly.

“You’re impacting their lives far beyond the boxing ring, man,” Coleman says of Cutty, who takes various street kids under his wing as a boxing coach. “If you’re going to embrace the level of leadership that’s required to be who he became, you have to know, This choice that I’m making matters. When you don’t know, you don’t recognize the domino effect of your actions.”

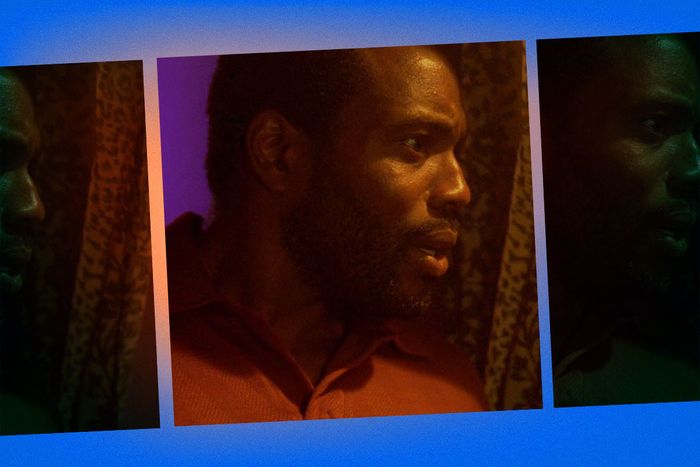

In the nearly 20 years since Cutty’s first appearance, in the episode “Time After Time,” the character has endured as a fan favorite because of Coleman’s mixture of vulnerability and intensity and what he describes as the “real ache” and “level of heat” he brought to Cutty. Coleman spoke to Vulture about navigating Cutty’s “Invisible Man complex” and the real Baltimoreans who added texture to his performance.

When I say the name Dennis “Cutty” Wise, what comes to your mind first?

Redemption. Change. This guy represented positivity. He was a shining example of how a person can start out on one side of the track and legitimately change their life. It makes me think of Calvin Ford. Calvin Ford is who the character’s life was based on. Dennis “Cutty” Wise, the name, was a murderer, and he changed his life, too, but Calvin is Gervonta Davis’s trainer, who made a 180 and became a successful boxing manager. The show is all about the failure of systems. It was very bleak. But here is this African American male who used to be muscle, ended up incarcerated, coming out and actually being one of the points of light for the show.

I remember being paired up with Calvin Ford at Upton Boxing Center. I just watched the man’s commitment and passion for those kids. One day we were in there and this 7-year-old kid is throwing haymakers, and I’m like, “Who is that?” He said, “That’s gonna be my new champion.” That was Gervonta “Tank” Davis, the now champion. I was there when he was like, “Tank ain’t here; his grandmother don’t know where he’s at,” and they were worried they were going to lose him to the streets. But when he came back, he never left, and Calvin made him a champion. It’s amazing, and I’m still friends with Calvin.

You’re joining a show that has already had two seasons, and you’re coming in as a new character for the third season. How did you prepare to join the series?

I knew most of the guys. Wood Harris [who plays Avon Barksdale] and I were roommates at one point. Steve Harris, his brother, is an actor as well. Steve said, “Chad, do you want to sublet my apartment in Hell’s Kitchen with my brother?” Because he was going out to Los Angeles to do The Practice. So me and Wood were roommates when Wood was at NYU.

And Wendell Pierce and I had already done a short film together, The Gilded Six Bits. I knew Andre Royo. Everybody was in New York doing Off Broadway theater. People think because we play the roles so well that we were not trained actors.

I knew a lot of the guys, and I was watching the show. I did a reading at the Public Theater, and we’re waiting for a guy for two hours — he’s late. The guy comes in, and he’s like [London accent], “What’s up, mate?” I was like, “You got marbles in your mouth?” It was Idris Elba! We do the reading, and I’m killing it, and after the show, in the dressing room, he said, “Man, you could be on The Wire — easy.” And I said, “Nah, man. They ain’t going to hire me.” I didn’t have the beard at the time, so when I’m clean-shaven, I look like a cop. A year later, I got the role, and when I got to the set, that dude picked me up. I’ve been calling him “the Prophet” ever since.

Me and Michael K. Williams — God rest his soul — I loved that brother. We used to be eyeing each other at auditions, like, Yo, he’s going to get this. And he’d be looking at me like, He’s gonna get this. And we became great friends.

The first time we meet Cutty, he’s standing in the Jessup prison yard between Wee-Bey Brice and Avon Barksdale, who has just been sentenced. Wee-Bey and Avon have the saying that you “only do two days” in prison: the day in and the day out. But from the beginning, Cutty refuses that with the line “I did 14 years.” His dryness and practicality tell us so much about him from the beginning.

I think Cutty was already having an inner, personal transition, and it was important for him to make that known. The time spent in there, even though we never delved into it, those were man-in-the-mirror years: Who am I really? Something inside, and I believe it to be spiritual — not religious — something changed in this man. Though he may not have been adept at articulating it, there was a sense of it, and he wasn’t going to let nobody take that from him: I’m at the doorstep of recidivism if I take in what they’re saying and the way they’re saying it. But at the same time, it’s a precarious deal because they see it as “We’re trying to support you, brother. We’re looking out for you.” They don’t understand the nature of what’s clicked inside of him.

I’m speaking about it in hindsight, in a much more sure way. Cutty was not on firm footing with it. He was trying, and that was the beginning of him finding his assuredness to get to the scene where he says, “It ain’t in me no more.” And my favorite part was not that; my favorite part was when they tried to bargain him into “You don’t have to do it. You can teach.” And he said, “None of it.” That was my favorite part. “None of it, man. I’m gone.” That’s monumental. I tell people often that there are more Cuttys in the world than there are Barksdales and Stringer Bells and Omars and Marlos. It’s kind of an Invisible Man complex because the dudes in the hood don’t see them no more because they’re not rocking like that. Society don’t see them because they’re ex-felons. And they themselves, a lot of times, it’s just tunnel vision: I ain’t got nothing to say to nobody because don’t nobody understand me. But when I was able to embody that role, to speak to so many guys and to have them applaud the journey and appreciate the truthfulness of it was huge for me.

Was that the first scene that you filmed as well?

Yeah. That was the approach for them — to not be skipping around, to make it feel like real-time evolution — and I appreciated that.

Did you have any rituals or routines as part of your process to get into Dennis?

The main thing was to get the boxing down. My buddy Jacinto Riddick, who is a trainer and an actor, was teaching me how to look like a boxer onscreen. By the time I hit the heavy bag at the end of season three and tore up my hands, I felt like I was a bona fide boxer. Training was before filming and while filming. Jamie [Hector] and I used to run together — run downtown by the Inner Harbor. All that training helped because you can only imagine that was a resource for Dennis — for him to decompress to a certain degree — coming back and being a fish out of water now. Those rituals were happening in prison as well. I think he learned to box in there. To keep that going, that gave him some sense of normalcy.

When you say a “fish out of water,” I think of Cutty’s clothes. A lot of his outfits in the third season are well kept but an older style. Can you talk to me about those looks? Were any your favorites?

Oh my God, I loved all of the sweat suits. The sweat suits were dope, man. The costuming — Alonzo Wilson was amazing. He would lay the stuff out and let me choose them, and I spoke to stuff that resonated from the ’80s: velvet, Adidas. They were very on point with how he’s a few steps off with his style, but it’s still got swagger.

I hate to call it the “assassination outfit,” but the black leather cap and the glasses in “Homecoming,” when Cutty goes to kill Fruit, are very stylish.

I chose that! They asked me, “What shades you want? What hat you want?” And I said, “He’s a throwback kind of guy, but yet it carries weight in the present.” That’s how I always felt about him. I distinctly remember choosing that. When you mentioned it, I was like, Oh, shoot, that’s right! I was like, “Nah, not this. Nah, not that. This is it right here.”

After Fruit steals Cutty’s package, Cutty tries to get a clean job in landscaping, which looks absolutely exhausting in the Baltimore heat and humidity. I know a Baltimore summer; it’s terrible. How much of that were you doing?

It’s hot as you-know-what. All of it — and I wanted to do it. That’s another way to just land in it. All that discomfort works for him because he hated doing it. I wanted to be hot and sweaty and do all that work for the aura of it: the discomfort, the frustration, the feeling like, Where the hell am I going to turn? This is what I gotta do?

The landscaping also made for some really tangible moments of growth. I’m thinking of his initial struggle with pulling the lawn mower to start and then, by the end, he’s using the equipment very easily; he’s speaking Spanish with his landscaping crewmates.

You watch this man and it’s not some hokey idea of change. It’s in real time, and it’s really hard and uncomfortable, but yet he’s making strides. He’s connecting with folks in a very real way because he’s a good man. He’s got a good heart. If you wreaked havoc on the community, what’s the best way to try to right that wrong? I think he was on that journey always, and yet there was the harsh reality of, Hey, buddy, you can only go but so far. This is your space in the world to try to change some lives, but they’ve gotta come to you.

There are a few scenes from season three that are real standouts for Cutty, and I’m hoping you can tell me everything you can remember about them. The first is the welcome-home party in “Hamsterdam,” when he’s looking into the rooms at this party and at the people doing drugs and hooking up inside. What did that entail?

Ernest Dickerson was the director, and I had the scene where I’m kind of macking the beautiful girl. We did that scene 14 times. I had to resist the impulse of like, Ooh, look at all these bodies! It wasn’t that. It was like, Oh, shit, I ain’t seen this stuff since whenever, and I’m having system overload. It’s actually freezing me. I don’t even know how to relate to it like that because I’ve been away from it for so long.

Once I got that glazed look going, then we had it. We were telling way more than just a story of the boys on the block hooking you up because you’re home. It was much deeper than that.

I wrote in my notes that he’s almost reacting to it like it’s a house of horrors. He’s lingering at each door, just looking inside. It’s a great contrast between how he is reacting and how Bodie is reacting — to Bodie, this is nothing.

Absolutely. It’s as pivotal as him walking up the block when he first got home and looking at all the blight and the dilapidated buildings. It was haunting in a lot of ways. He had to ride through that fun house of mirrors, twisted bizarreness, to finally reach a piece of his manhood. I’m biased, but I never thought that Cutty was celebrated to the degree that he should have been.

You mean when the show was airing?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I think people were more drawn to the bad guys; the bad guys are more sexy. But it’s like, Nah, you should really revisit this man and what he represented and all the subtle ways in which he was struggling or trying to relate in the world.

Rewatching Cutty’s episodes, it’s so noticeable how he has one foot in, one foot out. That leads me to the scene in which Cutty tries, and fails, to kill Fruit in “Homecoming.” Your body language is really important in that scene: You have the shooter’s pose, but you can’t do it. How did you prepare for that scene?

That one was hard. It took quite a few takes, and it took me looking at it to really get what you’re talking about. It was so much more than just aiming the gun and not being able to pull the trigger. I was doing it, and I was like, Mmm, this is forced. I’m not settling in on this right. I’m making a meal out of it. And then when I watched it, I was like, Oh, okay. I know what to do now. It’s all there already; there’s nothing you have to do but just really be present. Don’t try to tell us a story. Let the story tell itself.

Looking back, was that your most difficult scene to shoot?

The stare-down scene for sure was the most difficult for me, in that alleyway. To just really allow all that was at stake to resonate, without trying to telegraph anything, to make sure they get it — that was the hardest.

No, no, no, no. The hardest scene was having to do that physical slap of the girl in the street in “Straight and True.” That was like [grimaces], but I understood it. This is not a popularity contest. If viewers don’t like him, they have every right not to. This is the misogynistic, domestic-violence-ridden world that he comes from, so we’ve got to say it plain, and we’ve got to say it straight.

After Cutty is unable to kill Fruit, Slim Charles makes an excuse for his inability to act. He is very generous with Dennis afterward.

He was, even though he switched up when he got to Barksdale. That is actually my favorite line: “Nah, he a man today.”

After what Slim Charles says, which is, “He was a man in his time.”

I hope people don’t miss it. The biggest drug dealer in the hood is saying, “No, no, no. I see it. I can’t do that, and I could stand in the way. But I’m not, because I see somebody emerging.”

And later on, during Dennis’s fundraising conversation with Avon for his boxing gym, Avon’s respect for him does play a part in securing Dennis $15,000 when he originally asks for $10,000.

That’s a fun one. I made the choice to be like, I’mma go for it. I shouldn’t be asking for this much, but damn it, I’mma go for it. It was a perfect setup for him to go, “What? That ain’t nothing. Get the man the money.” At first, he’s being all dismissive, but I’m like, No. I’m going to fight through this, and this is going to happen. Look at the dream, bro! That was a precious scene with Wood.

I do want to ask about “It ain’t in me no more,” which is such an enduring line for Cutty. What was your reaction to reading that?

I was so deep in it. I wasn’t talking to nobody. I stayed away from everybody. He has to sit on so much, but if you don’t have it going inside your body, the scene is not going to rise to the expectation. It’s a mammoth scene — condensed, but it’s as huge as any Shakespearean moment. So I had to have that energy coursing through me. I was doing a lot of push-ups. It’s coming from your gut. It’s coming from a place inside you that you don’t absolutely know. Something is taking over you right now, and there ain’t no going back.

Was there any running through the scene beforehand with Wood or Anwan Glover, or did you just go in and do it?

Everybody knew, Okay, guys. We have but a couple of shots at this for it to really have the authenticity before it’s diminishing returns on this. This is very heavy. Everybody knew it, and everybody left me alone. We did it twice, and that was it. The level of heat that was coming off of me doing that one — that got so real.

The vulnerability of the whole scene works very well.

All men need classes in being vulnerable. That’s the problem with the world right now: too many men that are running from that vulnerability, which is a prime component to being a leader. In the hood, they just don’t give you space for what they consider softness, and it’s really not softness at all; it’s rounding out you as a human being. It’s being in touch with your humanity in a depraved circumstance. That’s the key to Cutty, for real.

When Cutty says to his ex-girlfriend Grace [Dravon James], “Looking at you”—

“Hurts.” And she says, “Shouldn’t look.”

That one! And the look on his face afterward? I just saw that one recently, and I was like, Lord have mercy. The look on his face that lingered! I was like, Wow, dude. Good stuff! When I look at it, I’m not looking at me. I’m looking at the story and the character. I’m able to do that; some actors can’t do that. Even the sun, even the way he was squinting — the way he looked in the car and saw the car seat — he came back for her. I always wrestle with it. The beauty of it was she was just being honest. But the weight of it! Talk about a kick in the face! Don’t look. She did it so amazing because it wasn’t like she was trying to diss him. She was honestly, sincerely saying, I’ve moved on. My life has evolved. We’re not going to pick this up from here. It’s not going to happen.

Everything’s coming back to me. Clarence Clemons as the gateway to the boxing world — to be able to hang out with that man, that’s something that I will never forget. He was a soulful person. And then, of course, Melvin [Williams]. He would just tell you what it was like in federal prison. He would say, “Chad, it ain’t no joke in there, man. Dude come up to you and say, ‘You’re gonna have my baby.’” I would spend time with Donnie Andrews, the real Omar. Donnie made the hair stand up. I knew he was a real killer. He wasn’t going, “Yeah, I killed people”; he would say, “Heh, heh, heh.” I was like, Oh my goodness, that’s a killer. And he changed his life. It was amazing to be in their presence. The fact that David Simon and Ed Burns had the wherewithal to bring these people in as consultants and then put them on the show — has it ever been done? And then Snoop [Felicia Pearson]! When Snoop said to me, “I ain’t used to white people being nice to me,” I was like, Wow. That’s as real as it gets. The condition, the circumstance, what she was up against. There will never be a show like that again because it’s married to reality in a way. And the lines are blurred with them being able to come in and act. It’s just incredible. It’s fine wine.

Was there any difference between how you played Cutty versus how you played Dennis? It’s a major moment when he starts going by the latter name, and I’m curious how you approached that distinction.

There was, absolutely. Cutty understood how to leverage his power, his physical prowess. He understood how to intimidate people. But Dennis figured out how to negotiate with people. He got in touch with his humanity in a way that he wasn’t afraid of it: I know who I am; I’m not trying to inflate who I am; I’m not trying to do ego. I’m simply calling this thing just the way it is. I have limitations — I can’t. I can only do but so much. But I’m resolved within myself with that. What I can do, I will do.

I want to ask you about your stare, which is an early intimidation tool for Cutty. Can you talk to me about finding that look, that expression, and what you wanted to convey with it?

In the script, they would say “eye-fuck.” And I hadn’t heard that before, but I was like, Oh, shit, I get that. And honestly, in every hood across the land, the eye-fuck is very real. You have to be able to freeze somebody with just your look. I have very intense eyes anyway, so I didn’t stand in the mirror and go, Okay, this is how I’m looking. I could feel it — you know what I’m saying? It was almost an inner monologue of, Say something, motherfucker. Say one thing to me. I dare you to say one goddamned thing to me.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More From This Series

- Amy Irving Answers Every Question We Have About Crossing Delancey

- Patrick Fischler Answers Every Question We Have About Mulholland Drive

- Nicholas Guest Answers Every Question We Have About Christmas Vacation