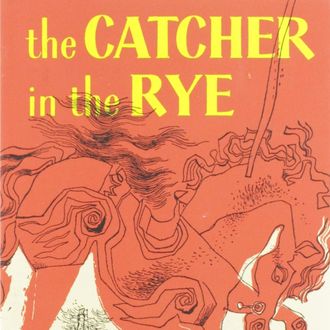

Last week, a debate erupted on Twitter over J. D. SalingerÔÇÖs 1951 novel, The Catcher in the Rye. A person posted a video on Twitter calling Holden Caulfield a first-generation incel and protoÔÇôschool shooter; defenders of Caulfield claimed he was a grieving abuse victim ÔÇö a teenager! ÔÇö who deserved our utmost sympathy. One viral tweet insisted, ÔÇ£Hating Holden Caulfield means you lack empathy, reading comprehension, or both.ÔÇØ

I loved The Catcher in the Rye as a teenager (red flag!?) and couldnÔÇÖt get into it as an adult. I donÔÇÖt hate Holden, though I donÔÇÖt ever want to hang out with him. HeÔÇÖs part of an esteemed class of literary characters: troubled outsiders. Or, more specifically, troubled outsiders who suck. He also isnÔÇÖt real, a detail that both sides of the argument seemed to forget. Since he isnÔÇÖt real, thereÔÇÖs nothing wrong with hating the guy. Nothing wrong with loving him, either. Though he has the qualities of a guy you might pass on the street, you wonÔÇÖt ever pass Holden on the street, because he does not and has never existed. Happy to say it again if I must.

The notion that readers ought to empathize with Holden, and that the failure to do so is indicative of a moral failing, is part of an ongoing trend in contemporary literature claiming that fiction can teach readers how to be more empathetic. The research started appearing about a decade ago, first in major newspapers and more recently as clickbaity life hacks: If youÔÇÖre a bad person, reading literary novels might teach you the value of kindness. Literature, however, canÔÇÖt make anyone kinder than anyone else; many of the worst people love cracking open a book.

Fiction isnÔÇÖt meant to make readers better people. It is meant to convey feeling ÔÇö awe, joy, love, beauty, and, yes, even empathy. Fictional characters, though they inspire intense feelings, are only ever collections of traits. Holden has shades of an incel, shades of a trauma victim, shades of a school shooter, shades of a grieving teenager. However, he isnÔÇÖt a human; heÔÇÖs a mirror held up to help readers process how they feel about real people who harbor similar traits. You canÔÇÖt empathize with a mirror.

As a reader, I routinely hate characters who have plenty in common with friends who remain in my life. I have forgiven loved ones for committing the same harms that have rendered many characters villains. This isnÔÇÖt a contradiction. My relationships to fictional people are not shaped by my relationships to real people, because ÔÇö and I feel embarrassed having to say this again ÔÇö real people are real, whereas fictional characters arenÔÇÖt. Hating Holden Caulfield doesnÔÇÖt mean you hate your depressed, grieving, traumatized brother. Empathizing with him wonÔÇÖt prepare you for when your child acts like a jerk and gets kicked out of school. But the novel is effective at what fiction is supposed to do: eliciting deep, profound, and uncomfortable feelings. What you do with those feelings? ThatÔÇÖs living.