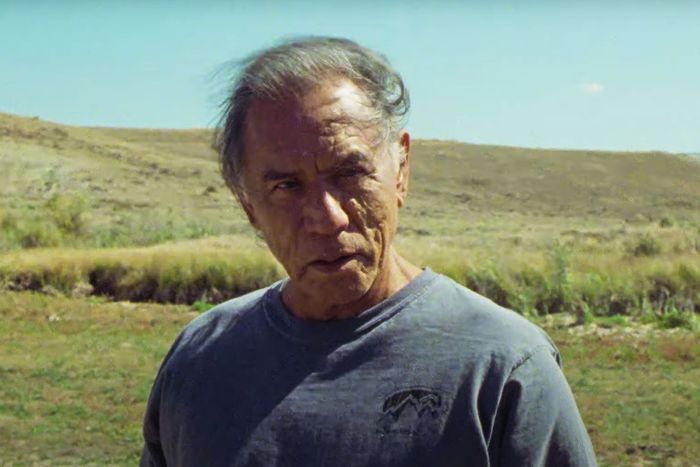

Wes Studi is one of the more recognizable faces in American cinema. And yet he didnÔÇÖt get to play a romantic lead until A Love Song, in which he and Dale Dickey play old friends who reconnect and try to rekindle their long-stifled passion for each other. The filmÔÇÖs novelty ÔÇö both Dickey and Studi are actors who tend to play, in his words, ÔÇ£tough guys,ÔÇØ and this is the first time either of them has shared a kiss with anyone onscreen ÔÇö doesnÔÇÖt quite do justice to its intimacy and simmering sense of longing. (Read my review of it here.) And for more than three decades, Studi has been bringing uncommon depth to a wide variety of parts. Of course, there was his breakthrough performance as the vengeful Huron warrior Magua in Michael MannÔÇÖs Last of the Mohicans (1992) as well as subsequent Native American roles in films such as Walter HillÔÇÖs Geronimo: An American Legend (1993), Terrence MalickÔÇÖs The New World (2005), and Scott CooperÔÇÖs Hostiles (2017). But he was also in MannÔÇÖs Heat (1995) and James CameronÔÇÖs Avatar (2009) as well as Mystery Men (1999) and Street Fighter (1994). His prolific career is all the more remarkable considering the fact that Studi didnÔÇÖt start regularly acting in film until his early 40s. Before that, he had already lived an eventful life, including a long period of activism in the American Indian Movement, which he joined after serving in Vietnam. Studi never abandoned his activism. He considers making films, especially influential ones, a responsibility. He adds, ÔÇ£A Love Song to me is the epitome of that road that IÔÇÖve asked myself to travel.ÔÇØ

I read that Max Walker-Silverman, the writer-director of A Love Song, had you in mind when he wrote this part. Did you know that when you read the script?

He told me that, that he had thought and thought and thought and thought of me and Dale for these parts. And of course I was flattered, but you never know as an actor if youÔÇÖre being told the truth or not. I was not only surprised, I was aghast. No, itÔÇÖs definitely a departure from what IÔÇÖve done before. For one thing, it was my first movie kiss. I think IÔÇÖve done one for television, but this was my first movie make out, if you will. And a very touching script. If youÔÇÖve seen the film, I think most people get the idea that, yeah, thatÔÇÖs an awkward situation these people are in. But they press forward, huh? They press forward because thatÔÇÖs what humans do.

Their earlier lives are just hinted at through lines of dialogue or even glances. We get a sense of a very rich past, but we donÔÇÖt actually ever hear about it. Did that require you to create a backstory for these characters while you were preparing?

ItÔÇÖs kind of like a spaghetti western. It doesnÔÇÖt necessarily have to do with shoot-ÔÇÖem-ups or hanging people or things that happen in a spaghetti western, but a lot of it is shot in that way. So much can be said or conveyed, if you will, with silences ÔÇö awkward silences, full silences ÔÇö or with just a look, right? A drop of a head or the widening of an eye, the slitting of an eye. Most of us in the current world, we communicate that way even if we donÔÇÖt use the words. But then sometimes a lot of us become accustomed to having to have words that just go on forever and ever and ever. For a stage player, thatÔÇÖs needed, right? But this story really revolves around the intimacy between the two characters, be they embracing or just coming together in a very awkward manner. ThatÔÇÖs the human condition.

We also get to see your musical side in this movie, which we often donÔÇÖt see in films. But youÔÇÖve actually been in a rock band, called Firecat of Discord.

Yeah, yeah. WeÔÇÖve played a number of places, even some iconic ones like the old Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tennessee. Played that one time. We played the Fillmore West and a number of Native casinos throughout the States. That was in the ÔÇÖ90s, I think. To get into the band, I had to play an instrument, and I also had to write a song or two in order to stay as a member of the group. And one of the songs had to do with the awkwardness that we feel in those situations that we were just talking about. So, yeah, IÔÇÖve been there.

I was really impressed by A Love SongÔÇÖs use of landscape.┬á

You know, on the actor call list, thereÔÇÖs No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3, right? The way I see it is that Dale would be No. 1, and then the Lone Cone would be No. 2, and then Lito, my character, would be No. 3. And then after that, thereÔÇÖs the crawdads. But I had seen one of the shorts that Max shot somewhere in that same area. He definitely incorporates the world that he is in love with there in Colorado. And he does have a sensitivity that is different. I mean, itÔÇÖs not like John Ford. Or itÔÇÖs John Ford, but a much more sensitive John Ford, if you will. He takes the time to incorporate the setting into what is happening with his characters and the way that they think of and deal with their environment. ItÔÇÖs very organic to me. The short film that he allowed me to see before coming to work entranced me.

When you read the script for A Love Song, did you know that you would be acting alongside Dale Dickey?

No, I didnÔÇÖt. It wasnÔÇÖt until maybe a week before I was headed up to Colorado that I learned, Oh, itÔÇÖs Dale Dickey. Great! I mean, weÔÇÖre kind of alike in terms of what weÔÇÖve done before. Our careers have been not the romantic leads. WeÔÇÖve been the tough guys or something like that. Not to toot my own horn or anything, but I think weÔÇÖve both been called ÔÇ£scene-stealers.ÔÇØ So does that mean that other actors donÔÇÖt want to work with us? [Laughs.] I love the fact that Dale gets so into her characters to the point that you canÔÇÖt not be present when youÔÇÖre working with her. It makes it very easy for me. But it also keeps you on your toes. You better be ready for anything that might happen.

You had a notable part in Dances With Wolves and then had a breakthrough role as Magua in Last of the Mohicans, which subsequently led to a lot of similar roles. Do you feel like you get pigeonholed in terms of the types of characters you play?

I can say that it would be very easy for filmmakers to do so. But there are adventurous filmmakers in the world as well. IÔÇÖve been lucky enough to do what I call sort of crossover films for me. I started out mainly in westerns, Native parts of all kinds. But I also played in films like Mystery Men, Street Fighter, and Heat, which allowed me to cross over from those parts. Those films have cult followings practically. As did Avatar. ItÔÇÖs just amazing how influential films can be. ThatÔÇÖs a responsibility as well. And A Love Song to me is the epitome of that road that IÔÇÖve asked myself to travel.

But you canÔÇÖt blame audiences for saying, Oh, yeah, thatÔÇÖs that Magua guy. But now heÔÇÖs playing someone else. And this Lito fellow in A Love Song doesnÔÇÖt have to deal with all of the dramatic components of MaguaÔÇÖs life. But as much as Magua was struggling with the kind of world that he was dealing with, LitoÔÇÖs doing the same thing, but on a much more cerebral personal level. And how to go about moving from point A to point B to C to all the way to the end of the alphabet is a much more internal thing. Perhaps thatÔÇÖs why there are so many silences in the film. So we can think, Wow, what could it be that heÔÇÖs thinking now? WhatÔÇÖs he going to do? Oh, okay. I didnÔÇÖt expect that. So you leave it to the audience. Throw it out there and see what happens.

Speaking of crossing over and not being pigeonholed, it was fun to see you in Heat, in another Michael Mann movie, right after Last of the Mohicans, doing a completely different part. That demonstrated your range fairly early on.

Yeah, I think that was actually my first cop part. I had just moved to Santa Fe at the time and was there for I donÔÇÖt know how long. But I heard that Michael was doing a film with De Niro and Pacino, who had never been in the same scene before. That was in the trade papers. So IÔÇÖm sitting around one day, and I thought, Hey, I still have the number for MannÔÇÖs production company, Forward Pass, here. I think IÔÇÖll call. So I called. A guy answers and says, ÔÇ£Who is this?ÔÇØ I explained who I was. ÔÇ£Oh, okay. Hold on a second.ÔÇØ And amazingly enough, Michael gets on the phone. ÔÇ£Hey, how are you doing?ÔÇØ Yada yada. WeÔÇÖre talking. I said to him, ÔÇ£Hey, I heard that youÔÇÖre doing a film with Pacino, De Niro, and me.ÔÇØ He kind of chuckled at that. And then went on to talk about something else. But a couple of weeks later, they said, ÔÇ£WeÔÇÖd like to talk with you and make an offer.ÔÇØ

Quite the learning experience that film was for me. We did ride-alongs with county police. And we were in the Rampart area of the city, patrolling with this one fellow. And a call comes in about a gang shooting that started with someone in a wheelchair. Someone in a wheelchair just got popped. And then within 30 to 45 minutes, there was a reciprocal shooting of the other gang. That happened four times in one night ÔÇö only to find out that the guy in the wheelchair was the wrong person. But that one and three others had been shot that night. I donÔÇÖt remember the fatality rate. That all happened within something like four hours on one evening in that part of town. It was something that these guys have to deal with on a daily basis. So that certainly informed the characters that we played, I think.

YouÔÇÖve done a lot of genre movies, particularly westerns. And I think we talked about this the last time I interviewed you, but it really can be a Catch-22 because westerns often indulge in these destructive myths even as they also provide a lot of opportunities for Native American actors.┬á

Yeah, yeah. And so how do you deal with that? I want to work. I want to become an actor. But whatÔÇÖs offered me at first is a perpetuation of the American myth. Okay. Well, maybe I can have an effect here. At least to say, Wait a minute, letÔÇÖs back off just a little bit here and deal with kind of a real issue. Dances With Wolves took a little more of a look into characters like Wind in His Hair and the Graham Greene character. We get to see that, Hey, these people are pretty much like everybody else in the world. They just have different customs. But I think that film was one of the first steps in recognizing the humanity of everyone involved. People said that itÔÇÖs like Lawrence of Arabia, and certainly, yes, it was to some extent. For the longest time, we dealt with that narrative about a white savior coming to save the world, or our world, or the NativesÔÇÖ world, if you will. This myth that we, as Native Americans, couldnÔÇÖt have survived unless the Europeans came and saved us with Christianity and this or that.

I hate to get off onto a rant here, but the pope is in Canada, right? YouÔÇÖve heard about the apology from the pope and all. I have to put in my two cents in terms of what the pope really needs to do, which is rescind, or do something about, the Doctrine of Discovery. That is the papal bull that legitimizes almost every kind of annihilation and genocidal activity thatÔÇÖs ever happened toward Natives in North America. That is something that he really needs to deal with in terms of either apologizing and/or rescinding that permission to go about and conquer the world or take all its riches. But I will stop there on that.

How did you get involved with the American Indian Movement?

I went to junior college in the 1970s, when the movement was building up here in the United States. There was the business at Alcatraz and the fishing-rights struggles up in the Northwest that captured everyoneÔÇÖs attention at that time. I had just returned from Vietnam, where I had come to the realization that for the past year I had been fighting on the wrong side of what was happening there.

When I first arrived in Vietnam, there were two of us ÔÇö two Natives ÔÇö in the company that I eventually spent my time there with. About two months into the whole thing, the other Native in my company committed suicide. I never realized why. We had talked about things, what we were doing there and stuff, but not to any great extent.

One of the things that happened around the time that I was there ÔÇö this was in ÔÇÖ68, ÔÇÖ69 ÔÇö was that Martin Luther King was assassinated. A lot of the Black guys in our company began to say things like, ÔÇ£They just killed Martin Luther King! What are we doing over here?ÔÇØ A lot of them stopped going out in the field, stopped participating. So they were hauled off to jail in Long Binh for defying orders.

There were times that our company would have to relocate entire villages of people. What we would do would be to take a huge net and put it out and ask all of the villagers to put all their belongings in this huge net that would be pulled up by a helicopter, which they called a Jolly Green Giant. What it reminded me of was the relocation of Cherokees from the Southeast to Oklahoma and to Indian Territory. The Trail of Tears, all of that.

The other thing was my skin color and what I looked like. There would be times when Vietnamese guys who had surrendered ÔÇö they were called ÔÇ£Chieu HoisÔÇØ ÔÇö would be our scouts. Sometimes I would talk to them or interact with them despite language being a barrier. But they would say things to me like, ÔÇ£Hey, you same, same Vietnamese.ÔÇØ Go like that [points to the skin on his hand]. ÔÇ£You same, same Vietnamese.ÔÇØ And I would begin to think about that. And itÔÇÖs true. Yeah, it hasnÔÇÖt been that long that who you were fighting is the same people that we were fighting a few years ago, and now IÔÇÖm on their side. That was a sociopolitical awakening on my part.

Then, when I came back, I had to deal with being called a baby killer, with how soldiers were treated when they returned from there. I got involved with Vietnam Veterans Against the War around that time. I was in Tulsa Junior College, and AIM was sending out people to universities and colleges, recruiting for this movement that was beginning. It was actually for the trip to D.C., the Trail of Broken Treaties, that really awakened everyone to the social situation ÔÇö and that there was something that we could do about it. We began to learn more about the idea of our own sovereignty in the States. That was what activated most of the youngsters in universities and colleges at the time. ThatÔÇÖs what built the movement. I was involved with a group called the National Indian Youth Council, which was a part of everything that happened out west. And then after that, the American Indian Movement started up in MinneapolisÔÇôSt. Paul and then spread from there. That was my radicalization, if you will, that happens to young people and/or older people as they begin to realize what their social and political situation is in this world. I needed it.

Was it true you were under FBI surveillance for a while?

Sure. Yeah. They used to sit in front of the house there. In fact, we started waving at each other after a while.

Do you remember the day you returned to the U.S. from Vietnam?

I remember we came back to I think San Diego. It was a Marine base there or something. We were told immediately to go down to the PX and get ourselves some civilian clothes and ship our duffle bag of belongings home. ÔÇ£DonÔÇÖt look like a soldier.ÔÇØ I remember getting off the plane into the airport and moved around in underground hallways. Moved to one place or another where we got civilian clothes. Then we got our bus tickets and were dropped off at the bus stations, and we went home in civilian clothes.

Do you feel like the film industry is improving in terms of Native American participation and representation?

We continue to enjoy better Native participation in the world of filmmaking and television programs. ItÔÇÖs just now blossoming actually in terms of how many more are involved in different aspects of filmmaking. In a way, until now, we have sort of been denied that, in that we didnÔÇÖt see that much of us except in the role of antagonist. And the role of antagonist was always a part of the mythology that we spoke of earlier, which led many people to the belief that we were wiped out, more or less, or that we live in tepees.

Is that improving? Are audiences getting smarter on such matters now?

I think they are. And theyÔÇÖre beginning to realize that theyÔÇÖve been fed a lot of mythology. I think people are learning more about who we are. And oddly enough, theyÔÇÖre beginning to not only deal with it but to enjoy what theyÔÇÖre learning.

This is not a new thing. Mythology has always been used to further a cause. In this case, the cause was building the American dream. Where does it come from? Well, we know that it comes from genocide, slavery, and things that we actually donÔÇÖt like to talk about having been a part of. And those of us in Hollywood and our predecessors have been involved in essentially building this mythology, which simply doesnÔÇÖt acknowledge the realities of how this nation came to be. But weÔÇÖre getting closer to it. I mean, self-examination doesnÔÇÖt hurt from time to time. And to know how you really came about is better than not knowing, I think.

More From This Series

- Paul Schrader Thought He Was Dying. So He Made a Movie About It.

- No One Sees the World Like Nickel Boys Director RaMell Ross

- ÔÇÿIÔÇÖd Better Watch Out or IÔÇÖm Gonna Fall in Love With This GuyÔÇÖ