At some point in 2021, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II decided he needed to build a life. Overnight, it seemed, the city planner turned actor had become one of Hollywood’s most in-demand leading men, after showing up as a delightful disco usurper in Baz Luhrmann’s Netflix series, The Get Down, his debut. The six years that followed were nonstop work — when he wasn’t shooting a movie (Candyman, Ambulance) or promoting a movie (The Matrix Resurrections, The Trial of the Chicago 7), he was shooting and promoting and winning an Emmy for the dual roles of a god and his corporeal form in the HBO series Watchmen. He was content with this structure at the time, but living peripatetically, going from set to set to set, gets old. The 36-year-old had moved to New York in 2015 yet hadn’t experienced a real summer in the city in his own apartment. “As soon as I started to want to just live a little bit, I was still working all the time,” he says, coolly sipping a raspberry iced tea at Freehold in Williamsburg. “That’s when I had to do something about it. And I did.”

He had already dropped out of Furiosa, the much-anticipated Mad Max: Fury Road prequel that would’ve had him away for three or four more years, and planned to take half a year off (though it turned into nine months). During this break, he’d ride his bike and hang out in Prospect Park. He’d buy plants and try to keep them alive. “I had other opportunities to work, but it didn’t feel like a whole lot of hot scripts were out,” he says. “I got the indication that I’m going to have to wait and trust that the right thing will show up.”

What showed up wasn’t a movie. It was Topdog/Underdog, the Pulitzer-winning Suzan-Lori Parks play about a pair of brothers locked in a cosmic hustle — Cain and Abel and card tricks. “This came in my ‘box,’ ” Abdul-Mateen begins. “And it was like, ‘What’s up? Topdog/Underdog. Broadway. What you gon’ do?’ ” That wasn’t the message in its entirety, but it’s how he read it: like a challenge. Like a dare.

The play, which turns 20 this year and is returning to Broadway for its first revival, is a sparse two-hander on a single set; the environment, Parks’s notes say, is “here,” and the time is “now.” Lincoln (Corey Hawkins) is the elder brother to Abdul-Mateen’s Booth and is an excellent three-card-monte dealer with a quick tongue and quicker hands, but he gave up the hustle. Now he works as a whiteface Abraham Lincoln impersonator, dramatizing the 16th president’s assassination on a loop for an arcade’s audience. Booth is trying to be an excellent three-card-monte dealer. He wants to coax Lincoln back to — or just beat him at — his old scam.

They’re brothers and mirrors and playmates and rivals. Therein lies the essential power struggle: Booth wants to be a man and to be babied all at once. The character is crass and animated and tragic — rich material for any performer. “Over the years,” Parks tells me, “it’s become one of those plays that you pull from when you wanna strut your stuff.” When it opened Off Broadway at the Public and then premiered on Broadway, the Booth role attracted a movie star and a rapper: Don Cheadle and Yasiin Bey, then known as Mos Def. (Jeffrey Wright played Lincoln opposite each.)

Abdul-Mateen wouldn’t have said yes to doing the show, his Broadway first, if it weren’t for Booth. As an undergrad at UC Berkeley, he studied architecture but took a theater class. For a showcase, he performed a composite of a few scenes from Topdog/Underdog. He was an amateur performer in his early 20s, so he played Booth as his own age — loudly rebellious, desperate to disobey — and remembers it feeling like “the first piece of theater that was written for me.” After Berkeley, he had a career in city planning in San Francisco. But semi-privately, he was attending night classes at the American Conservatory Theater for fun and ultimately turned his acting hobby into his full-time passion.

When he arrived at the David Geffen School of Drama at Yale in 2012, he was either older or younger than his classmates or less accomplished. He’d still performed only casually. “I didn’t consider myself an actor when I was at Yale. I felt like everybody else was. Some people had been on Broadway in Tony Award–winning performances. I was just a dude up there who was like, Man, a couple years ago, I was working in an office, taking my little class at night.” The head of the department took note of this during their first-semester check-in. “He told me I was backfooting. He wanted me to take up more space.”

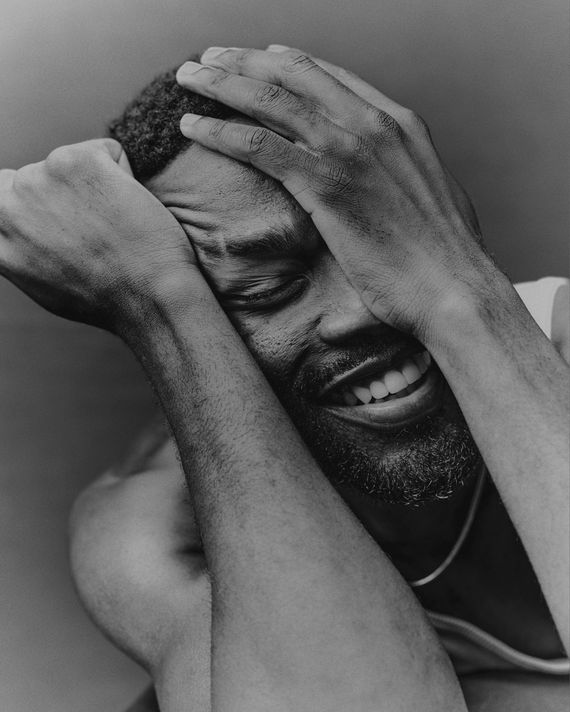

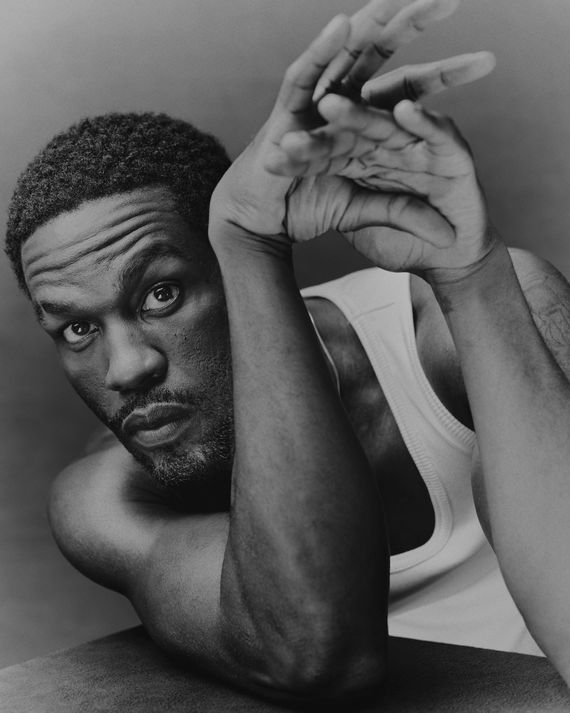

It should be said that Abdul-Mateen is six-foot-three; even today, casually slouching at a patio table, he sits wide and loose, alternating between excited rambling and a low drawl. It seems impossible for this guy — Aquaman’s Manta! — to make himself small. But his gregariousness is tempered; he can turn the charisma up or down. I was a few minutes early to our meeting, checking my phone until I caught the time and looked around to see if he’d arrived. I was taken aback at Abdul-Mateen, across the empty yard, nonchalantly sitting on another table and staring right at me with a gigawatt grin. He seemed pleased that he’d surprised me. But in conversation, he was slow and ruminative. I almost asked some questions twice because he took so long to answer I wasn’t sure if he’d heard me.

Booth doesn’t have the same emotional dexterity. He’s driven by so many needs and wants that are often in conflict; they come out in brash, showy ways. Abdul-Mateen is more attuned to that now that he’s older, playing Booth as older, too. He hadn’t revisited the material since college “but had it in my brain” the whole time. “The first journey around, it was a lot of angst, longing to get the girl and to move your life forward. What does it mean to feel unfulfilled as a 21-year-old? He wanted to have a good time. He wanted his life to be a little bit better,” Abdul-Mateen says. “This time, I’m very interested in saying, ‘What does it mean to be in this position in Booth’s life as a 36-year-old?’ To be in your 30s and feel like you have potential that’s untapped and your life isn’t going anywhere, that’s a completely different story.”

None of that comes at the expense of Booth’s easy charm as Parks wrote him on the page. It adds to the sum of Booth’s turmoil. Abdul-Mateen, the youngest of six (it’s “too simplistic,” he says, to figure that’s what drew him to playing a younger brother), was born in New Orleans and grew up in Oakland, and he considers Booth a “great mix” of the two: “He don’t care what nobody think about him. He got a smart mouth. He gon’ to tell you what he say. He’s got a romantic side, very braggadocious,” he says. That’s the New Orleans, Abdul-Mateen reports. His Booth will be sly and bombastic, “something they call ‘putting ten on a two.’ Do they say that out here?”

“Like being very extra,” I offer. “Doing the most.”

“Doing the mooost,” he says, stretching out the word. “Extra it out! That’s who Booth is.”

One of Abdul-Mateen’s earliest challenges as a new actor was to gauge when he should do the most. “In school, a student has the tendency to want to show I’m using all the tools! The independent artists find what best suits their instrument and needs. That’s one of the things that I’ve had to learn to fine-tune over the years.” The best acting is when the audience can feel the work, not necessarily see it. His Bobby Seale is one of the only parts of Chicago 7 that seems tethered to reality in spite of Aaron Sorkin’s cartoonish script. His Dr. Manhattan in Watchmen was imbued with tenderness in spite of the stiff constraints of playing someone with an unknowable consciousness. The joy of his Get Down character wasn’t only that he was handsome but that he shimmied off the screen, a thrill every time we got to see him. As Topdog/Underdog director Kenny Leon puts it, “He takes you somewhere you haven’t been.”

But how does the process for Topdog/Underdog compare to something big and loud like Aquaman? “Everything should be about getting to the truth. But sometimes you got to know which movie or genre you’re in,” Abdul-Mateen says. “Something like Aquaman, that’s clown work. Aquaman is not The Trial of the Chicago 7. You gotta get over yourself.” He puts the clown designation a different way: “In order to survive and to do it well, you have to play that game and then be crafty about when you want to surprise the audience, the director, or yourself with a little bit of ‘Wow, I didn’t expect to see a Chekhovian thing or August Wilson and Aquaman, but I did.’ ”

Topdog/Underdog begins previews September 27.