With her death at the age of 96, the immediate impulse is to measure Elizabeth II’s life by how much she saw the world change. She was queen during the first moon landing. She was already a grandmother when Ronald Reagan was inaugurated. She was born a decade before the invention of the chocolate-chip cookie. More to the point, though, Elizabeth II came to the throne at precisely the historical moment television became widely accessible to the public. Hers was the first live televised coronation, the first moment British citizens could see their monarch inside Westminster Abbey being handed the royal regalia. Unlike any of her predecessors, Elizabeth in public had to be carefully calibrated not just for print reporting, or radio broadcast, but for her live physical image. She was the first celebrity ruler in the age of modern media.

She may well have hated it. It’s impossible to know — Elizabeth II was, of course, impeccably formal in her exterior life, eschewing any sort of goopy detail-riddled interview about her daily existence and shielding the royal family from as much publicity as possible. A 1992 speech was the closest she ever came to admitting how painful persistent celebrity and media criticism was for her. After asking for “moderation and compassion” from “those whose task it is in life to offer instant opinions on all things great and small,” she continued, in her steady, prim rhythms, to call for some relief from the media onslaught. “Scrutiny,” she remarked mildly, “can be just as effective if it is made with a touch of gentleness, good humor, and understanding.” That year, two of her children’s marriages had fallen apart, the rift between Diana and the royal family exploded into public scandal, and, four days before the speech, Windsor Castle burned.

Fictionalized representations of her have speculated on Elizabeth’s private feelings about the media. Helen Mirren’s The Queen depicted her as someone deeply private, frustrated by the British public’s inability to separate her family life from her public role, and unwilling to make her family even more vulnerable for purposes mass consumption. In the Netflix series The Crown, she is pragmatic, seeking to keep the whole family out of the press as much as possible, in part to protect them and in part to protect the crown (and, by extension, for herself). Both of these Elizabeths are conjectural. If she did resent the burden of her celebrity, that one composed, unruffled speech was the most direct evidence she ever gave.

We remember the silhouette on the stamps, the never fully happy smile, the pristine wardrobe. She was the ribbon-cutter. The Christmas-address-giver. The dog lover. (Is there any more eerily innocuous, oddly empty defining trait than to be a dog lover?) She appeared through windows and on balconies, constantly seen but nearly always from the safety and control of her own defined space. Diana was the People’s Princess, somewhat like Elizabeth’s sister Margaret before her but without the acid tongue; Elizabeth II, by unmistakable contrast, was not. By dint of being the irreproachable, inaccessible, distant queen for everyone, she was never really, personally, yours. This flattened, sketchy perception is even more true in America, where the oddity of a monarch existing at all distorted her into something mascotlike, maybe even adorable. But certainly not human.

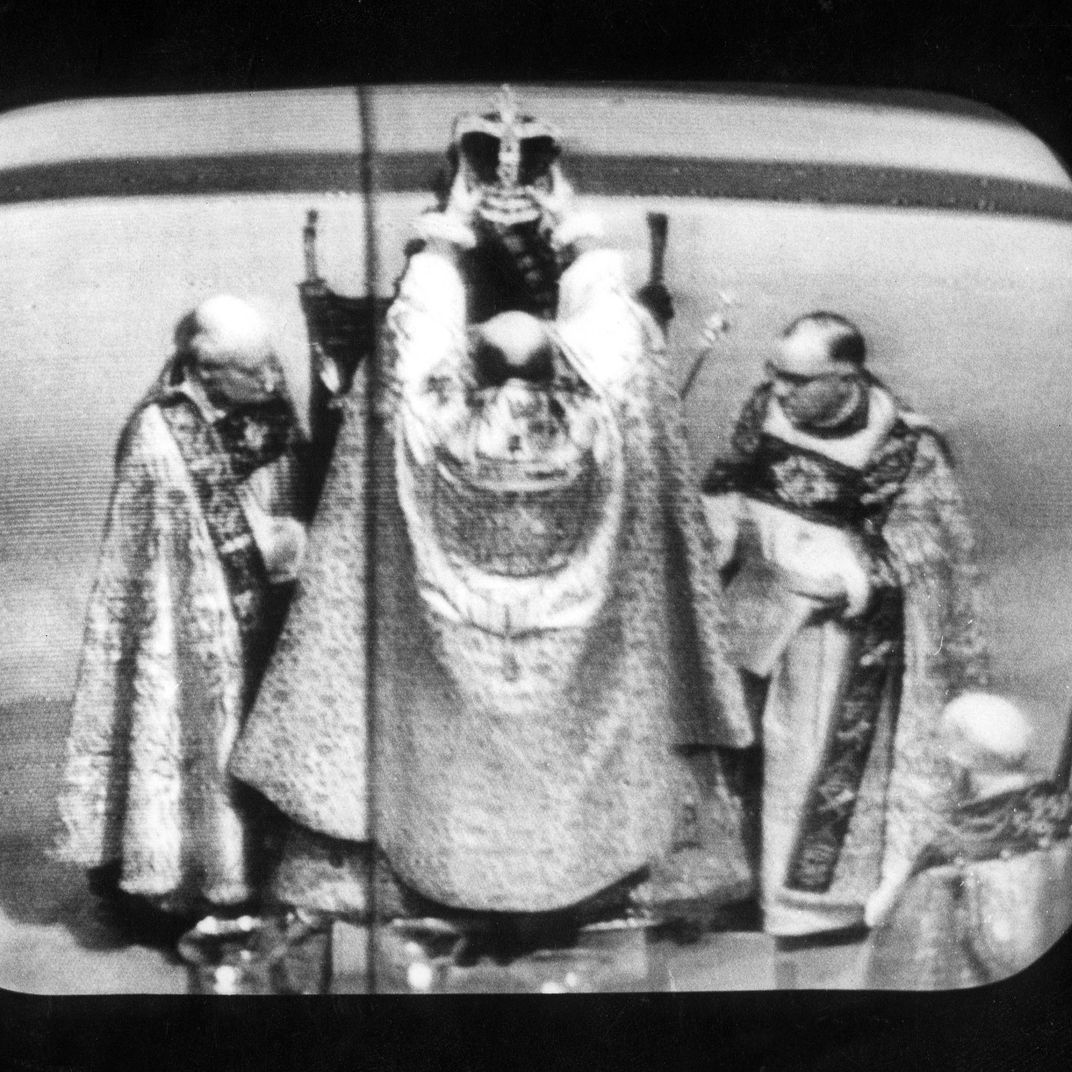

From the broadcast of Elizabeth’s coronation at Westminster Abbey on June 2, 1953.

Princess Elizabeth greets Winston Churchill at Guildhall on March 23, 1950.

With Charles and Anne at Balmoral in 1952.

On a state visit to Ghana, dancing with Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah in 1961.

With Prince Phillip during an interview for the Sunday Times of London in 1966.

From the broadcast of Elizabeth’s coronation at Westminster Abbey on June 2, 1953.

Princess Elizabeth greets Winston Churchill at Guildhall on March 23, 1950.

With Charles and Anne at Balmoral in 1952.

On a state visit to Ghana, dancing with Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah in 1961.

With Prince Phillip during an interview for the Sunday Times of London in 1966.

Elizabeth’s image as the queen waving from afar was shaped from the earliest years of her reign, as she and Philip left their young children at home and set off on a massive, painstakingly organized Commonwealth Tour. On the ground, it was a grueling, careful, months-long trip around the globe meant to solidify Elizabeth’s role as Queen. Back in Britain, it was transmuted into a long run of film reel appearances: snippets of parades, foreign countries, and distant clips of her giving ceremonial greetings. The concept of a British Commonwealth was held together almost entirely by this one young woman’s arrival and ceremonial procession through various countries’ capital cities, by fistfuls of confetti being thrown into the streets, and by Elizabeth’s calmly immobile expression.

When that filmed version of monarchy began to look too chilly and alien, Elizabeth’s image machine took another tack. The 1969 documentary Royal Family was a behind-the-scenes look at the Windsors at home, apparently showing everything from Philip cooking sausages to family sitting around the breakfast table and Elizabeth producing some less-than-sparkling small talk with President Nixon. It was an early example of everything we later took for granted about how to build celebrity — the combination of fundamental inaccessibility with a carefully filtered layer of “They’re just like us!” Royal Family was hugely successful with the public; it was rebroadcast on another station a week later and replayed repeatedly thereafter. It was so successful, and so fully flattened the royal image, that the Palace removed it from circulation, and it’s never been seen in its entirety again.

The collision between public and private that the Royal Family documentary caught is the key to the fundamental tensions in her life and her reign. Elizabeth had little in the way of actual power. When her father came to the throne, his title was George V, King of the United Kingdom and British Dominions and Emperor of India. At the time of Elizabeth’s death, the remnants of the British empire are entirely vestigial: Commonwealth countries are self-governing, regardless of what the portrait on their currency might suggest. The amorphous, intangible potency of being granted divine right to rule became just a divine right to … be the queen. And the meaning of that role fell entirely on her manners, her clothing, her marriage, and her children. Elizabeth’s deep reticence toward revealing her private self came smack up against TV and celebrity culture’s increasingly insatiable thirst for personal detail.

Inevitably, the consequence of a monarchal image held up only by one family’s identity resulted in moments of slippage. And because there was so little else to define Elizabeth’s purpose, the terrible periods in Elizabeth’s reign are not instances of international crisis or domestic policy failures. The terrible moments, most notably her infamous annus horribilis, are times of personal, familial calamity. They were the tension over her sister’s affair with Peter Townsend (as depicted extensively in the Netflix series The Crown), the dissolution of her children’s marriages, the tragedy and chaos of Diana’s death, the awful revelations about and subsequent casting-out of Prince Andrew, the rotten treatment of Meghan Markle. For all her dedication to charity, even though her refusal to participate in Commonwealth affairs sped up the process of decolonization, and in spite of international tiffs over the Suez Canal and Grenada and the Falkland Islands, the shape of her reign is outlined by her personal life, and that of her family. And in the absence of her own public volubility or a necessary public role, that family life has frequently co-opted her narrative. She is Elizabeth, who presents a smooth, unruffled public facade while behind closed doors, her children’s romantic and interpersonal lives teeter between scandal, collapse, and tragedy.

Elizabeth II was not the first queen of England whose visible public self became tangled up with technology and all kinds of broader cultural connotation. Victoria, the first English monarch in the age of photography, became an important icon for women’s comportment and mourning in the Victorian age. Her public image coalesced out of the combination of her imperial (literally, empire-building) majesty and her devoted, loyal widowhood. Going back even farther, Elizabeth I used portraiture and the relatively recent boom in printing presses to create and bolster the myth of her continual youth and availability, yet another potent admixture of the personal with the monarchal.

But unlike her predecessors, Elizabeth II was the first to rule at a time when the very existence of a British monarchy was becoming suspect. Her every public signal, from the refusal to allow close-ups at the coronation to the relentlessly formal public speeches to the quashing of the Royal Family documentary to the utterly prim persona hints at Elizabeth’s deeply held reluctance reveal. What else could you do if your entire personal life became the sole constituent element of a monarchal rule? How can we blame her for the opacity, the distance, the chilly persona of a grandmother who loved you but who never hugged you very tightly? But it’s no surprise that a figurehead monarch who consistently refused to be an especially fascinating, individual, charismatic figurehead coincided with widespread doubts about the utility of having a monarch at all. For someone whose whole life’s purpose was to exemplify and hold up the institution of the British monarchy, it’s tragic that the darkest moments in her reign were not when people rallied around her; instead, those were the times when the public began to question the utility and relevance of having a royal family at all.

Yet, paradoxically, the regular waves of anti-monarchism were held at bay largely by the sheer, irrefutable fact of her continued existence. What, were you going to depose the queen? Who would she be, if not the queen? What would Britain be?

Meeting President Nyrere of Tanzania in Buckingham Palace during the filming of the 1969 BBC documentary Royal Family.

At Aberdeen Airport with the corgis, beginning her holiday at Balmoral in 1974.

With princes William and Harry in the royal box at Guards Polo Club, June 14, 1987.

Addressing the nation the night before Princess Diana’s funeral in 1997.

Touring the Royal Albert Hall after its rebuilding, March 30, 2004.

At the Drapers’ Livery Hall in London in 2014.

Meeting President Nyrere of Tanzania in Buckingham Palace during the filming of the 1969 BBC documentary Royal Family.

At Aberdeen Airport with the corgis, beginning her holiday at Balmoral in 1974.

With princes William and Harry in the royal box at Guards Polo Club, June 14, 1987.

Addressing the nation the night before Princess Diana’s funeral in 1997.

Touring the Royal Albert Hall after its rebuilding, March 30, 2004.

At the Drapers’ Livery Hall in London in 2014.

What will it be now? For better and for worse, this is the challenge Charles inherits. He comes to a throne entirely reduced to a cult of personality, rendered empty of all meaning except what he, himself, his person, brings to it. And he will be free of many of the trials his mother had to endure. He is already a grandfather, his selfhood has long since formed, and his own public persona (such as it is) is already well known. His familial rifts have formed too — his youngest son has run as far from the royal family as he possibly can, citing cruelty and racism after his marriage to Meghan Markle. The cycle of a new generation bucking against the restrictions and blindspots of the older one has been in progress for years, long before Charles ever had a chance to take charge.

Charles’s reign will be far shorter than his mother’s. He is hampered by the awkwardness of having lived the majority of his life as an understudy, waiting to assume a role no one’s especially excited for him to take up. He seems to be, if anything, even less comfortable as a public figure than his mother was. His sons, who have had to grow up with a cannier and more transactional understanding of celebrity, will continue to make Charles look fusty by comparison. My guess is that his rule will not much differ from the model established by his mother – the monarchy as distant and generally well-meaning but not especially relevant or human. He’s not even known as a dog lover.

Because in spite of the drama and tragedy of Diana, and in spite of the subsequent scandal of Camilla, it’s hard to imagine Charles eclipsing the undeniable force of Elizabeth’s iconography. In praise and in satire, she was herself, a figure who represented an ancient Establishment and a traditionalist understanding of Britain. At the same time, she was a woman who lived on the world stage for decades, defining her own rock-steady public self in defiance of social fashion or transient political pressure, remaining resiliently private.

It’s hard not to see in her the herald of so many of our current debates about power and femininity, privacy and exposure, all wrapped up in a package so familiar and great-grandmotherly that it was easy to overlook. One forgets that when she was young, she was seen not as a distant anachronism but instead an accessible fresh face. For someone whose existence often seemed to be a relic, Elizabeth’s actual reign looks strikingly modern, from televised coronation to image-making to public family scandal. Maybe most of all, especially from the perspective of the last several American years, her reign suggests how little we think of leadership as being about specific policies or agendas. We’re all too happy to leave those things to the less visible, less decorated, less culturally meaningful public servants. Instead, Elizabeth II as queen proved the durability of solely symbolic leadership, of ruler as public image first and foremost.

It seems unfair, even somewhat cruel, to reduce her life so completely to her persona – to consider her legacy as ultimately one that produced a remarkable, era-defining, oddly immobile, impersonal public symbol. But that’s really all she gave us. Her private self, which countless biographies, movies, TV series and tabloid speculations have endlessly sought, remains largely anecdotal. She proved that a mask of power and meaning even in the absence of political force, could still define a national self. In the end, I don’t know whether it makes much difference whether she wore that mask, or whether she truly was the mask.

In either case, she was irrevocably, unmistakably, and perpetually, the queen.

More on queen elizabeth ii

- Imelda Staunton Was Playing Queen Elizabeth When Queen Elizabeth Died

- How Many Hats Are in the Trailer for The Crown’s Final Episodes?

- Mum’s the Word: Elizabeth Remains a Cipher in New Biography The Queen: Her Life