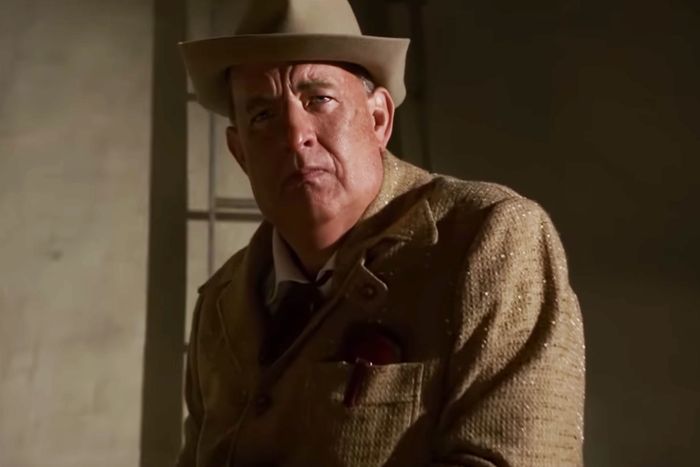

Point a funhouse mirror at an ordinary, by-the-numbers rock-and-roll biopic, and the distorted reflection will look an awful lot like Elvis. Everything is more exaggerated and grotesque in Baz Luhrmann’s surprise summer hit, now available to stream on HBO Max — including, and perhaps especially, the supporting performance delivered by the movie’s biggest marquee attraction, Tom Hanks. To play Colonel Tom Parker, the infamously exploitative manager of Elvis Presley, Hanks dons mounds of prosthetic enhancements: a fake nose here, baggy glue-on jowls there, padding that lends him roughly the same bulbous shape as Jim Broadbent in Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge. Factor in a labored Dutch accent, and his turn flirts with outright parody of the makeup-abetted celebrity impressions that so often go over big on Oscar night.

Written with a hindsight historical understanding of just how fully the real Parker took advantage of his client, the fictionalized ringleader-parasite version we meet in Elvis comes across as the most flatly detestable character on Hanks’s entire résumé. Which is to say, the actor who played Forrest Gump, Sheriff Woody, and Walt Disney has never gone this unambiguously, irredeemably bad before. Unfortunately, the two-time Oscar winner has also never delivered such a broad, silly performance — a ghoulish Saturday Night Live caricature of showbiz vampirism. How did this bold casting coup go so wrong? How did Elvis botch such a theoretically juicy pairing of movie star and scenery-chewing role?

It’s tempting to call it a case of simple miscasting against type — of Luhrmann taking a big swing and a miss by trying to pass off our most upstanding of movie stars as a notorious bloodsucker. After all, Hanks’s CV reads in general like a “nice” list compiled by Santa Claus (another iconic do-gooder, incidentally, whom Hanks has portrayed). It was probably in the ’90s, after Gump landed him a second Academy Award, that the star’s reputation as a (nay: the) virtuous Everyman began to crystallize. Years later, he has reached the point in his life and body of work where his very presence confers the impression of paternal decency and trustworthiness. Not for nothing is he sometimes referred to as America’s dad.

Of course, not every character in Hanks’s repertoire is an incorruptible Boy Scout. He has played some imperfect souls and morally shady customers: a clueless yuppie, a vengeful hitman, a slick congressman, a slightly sinister tech mogul, a brutish gangster turned best-selling author, and — in his directorial debut — a music manager not so different in his bottom-line calculus from the scheming, real-life gargoyle he plays in Elvis. Even the plastic cowboy Woody, one of the most beloved figures in all of animation, has unflattering traits; his jealousy and petulance are the driving forces of Toy Story. (One has to wonder if Pixar got away with making the hero of their first feature so winningly flawed because an eternally likable star voiced him.)

Still, it’s exceptionally rare to see Hanks cast as the flat-out villain of a movie. That’s what makes his turn as Parker such an outlier. Naturally, Hanks strives to find something human and relatable in the man, emphasizing his pathetic rationalizations and the theoretically sympathetic frailty of his elder years. But Elvis subscribes fully to the now-popular conception of Parker as a leech who bled his cash cow dry — a con man who kept an iron grip on Presley’s finances, enabled (and even fed) his addiction, and forced him into a casino residency that became a kind of luxury prison. He’s a Mephistophelian figure, seducing Elvis with promises of greater things, like the Mr. Dark of Ray Bradury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes. It’s telling that, in Elvis, he signs the King at a fairground — an ominously Faustian scene.

There’s a germ of a canny idea in putting Hanks in such a dastardly new context, in securing him to play such an unscrupulous man. The arc of Elvis depends on its title character’s believing his manager can be trusted and failing to see the calculating greed beneath his twinkling promises and fatherly advice. That the movie is narrated by Parker should, in theory, put uninformed viewers in the same position as the budding rock star — which is to say, invite them to mistake a music-biz Lucifer for an eccentric fairy godfather. Why shouldn’t Elvis trust Parker? He’s played by Tom Hanks!

Luhrmann had a lot to play with here, a whole onscreen legacy to weaponize. The thing about Hanks is that he’s a movie star in the classic sense, a living throwback to Hollywood paradigms of noble, levelheaded masculinity like Gregory Peck and Jimmy Stewart. Though his back-to-back Oscar wins for Philadelphia and Gump suggested a reasonably wide range, they did not pivot him into a chameleon’s career. Instead, Hanks has largely offered variations on an established type, allowing filmmakers like Ron Howard, Steven Spielberg, and Paul Greengrass to build movies around the qualities he sturdily embodies: moral clarity, kindness, understated valor. He’s a one-man shorthand for a certain idealized American spirit. And when he’s cast as a real person, it’s usually for the way his own comforting qualities as an icon can evoke someone else’s, even serving as a proxy for — in the most pertinent example — the comparable wholesomeness of Fred Rogers.

Alas, Elvis fails to fully capitalize on its own stunt casting. Rather than exploit the audience’s associations with Hanks, it buries them under mounds of makeup. What that ridiculous, Professor Klumpian getup suggests is that Luhrmann (or at least his financiers) refused to believe that audiences would accept Hanks as a bad guy without the visual aid of a total physical transformation. In a sense, it’s the opposite tactic of the one It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood employs. There, director Marielle Heller did little to disguise the star because the idea of Hanks as Hollywood’s premier backbone of essential goodness is basically identical to the film’s conception of Mr. Rogers. In Elvis, the approach is basically to hide Hanks, lest our knee-jerk fondness for him clash too much with Parker’s malevolence.

To that end, the past Hanks performance this new one most resembles is his over-the-top turn as a Southern dandy crook in the Coen brothers’ widely reviled remake of The Ladykillers. There, too, all of the Hanksian hallmarks are buried deep underneath an ostentatious sketch-comedy routine, complete with loud wardrobe, outrageous accent, and outsize physicality. Is Hanks now so synonymous with virtue and integrity in the public eye that he has to be wholly caricatured — to be turned into a living cartoon — to convince as a scoundrel? It’s telling that his few stabs at playing someone truly unlikable have resorted to ridiculous costume-chest, dinner-theater dress-up, ditching all of the qualities (and relaxed charisma) we associate with him.

The irony is that we never really forget whom we’re watching in Elvis. Hanks has no special talent for impersonation; accepting him as a recognizable historical figure requires seeing a productive kinship between his persona and someone else’s. Here, attempting to obscure how Hanks usually looks, sounds, and behaves onscreen paradoxically leaves all his labor exposed. He’s transparent in latex and oddball pronunciation. The best that can be said for his performance in Elvis is that it’s in keeping with the big-top theatricality of the material — and with the conception of Parker as an ersatz cowboy, a fraud entrepreneur for the ages. (That Hanks sounds nothing like the real Parker could be read as a dramatic choice, however distracting.)

In their comical huffing and puffing, the vaudevillian heel turns of Elvis and The Ladykillers are half measures for an actor still only flirting with true villainy. They obscure Hanks’s image as Hollywood’s perennial good guy. To truly subvert it, he’d need to go full Henry Fonda in Once Upon a Time in the West, draining his heroic persona of all mercy and compassion. Everyone has a dark side. What a shock and thrill it would be to see Hanks truly get in touch with his without the crutch of quotation marks or fat suits.